ePostcard #104: Witches’ Brooms & Rust Cups (Tierra del Fuego)

ePostcard #104: Witches’ Brooms & Rust Cups (Tierra del Fuego)

Rust fungi get their name because they are most commonly observed as deposits of powdery rust-colored, yellowish or blackish spores on plant surfaces. Rust fungi are obligate plant pathogens that only infect living plants, and are well known for causing conspicuous abnormal growths, including galls, stem cankers, witches’ brooms and other plant malformations. Witches’ brooms, which consist of an excessive growth of branches from a single point on a branch, are symptomatic of fungal rust infections on specific host plants caused by pathogenic fungi of the order Pucciniales. An estimated 168 rust genera and approximately 7,000 species, more than half of which belong to the genus Puccinia, are currently known to science. Rust fungi are highly specialized plant pathogens with several unique features that affect many kinds of plants. Each species has a very narrow range of hosts and cannot be transmitted to non-host plants.

Commonly known as Calafate rust, Aecidium magellanicum (photos #1, #4, and #5), is the species of rust fungus that infects the evergreen shrub Calafate (Berberis buxifolia) in Argentina and Chile. It produces one of the most colorful witches’ brooms I’ve ever seen, with an excessive growth of stems and crimson leaves arising from a single point on a branch. Rust fungi grow intracellularly, and make spore-producing fruiting bodies within or, more often, on the surfaces of affected plant parts. The spores of rust fungi may be dispersed by wind, water or insect vectors. Each spore type is host specific, and typically infects only one kind of plant. Infections begin when a rust spore lands on a susceptible plant surface and germinates, growing a short hypha called a germ tube. The germ tube typically locates a stoma (a micropore in the leaf epidermis) by a touch responsive process known as thigmotropism, through which the tube invades its host. Infection is limited to plant parts such as leaves, petioles, tender shoots, stem, fruits, etc. Plants with severe rust infection may appear stunted, chlorotic (yellowed), or may display signs of infection such as rust fruiting bodies. A single species of rust fungi may be able to infect two different plant hosts in different stages of its life cycle, and may produce up to five morphologically and cytologically distinct spore-producing structures (spermogonia, aecia, uredinia, telia, and basidia) in successive stages of reproduction.

Once the fungus has invaded the plant, it grows into plant mesophyll cells, producing specialized hyphae known as haustoria. The haustoria penetrate cell walls but not cell membrances: plant cell membranes form a pouch around the main haustorial body, creating a space known as the extra-haustorial matrix. An iron and phosphorus rich neck band, known as an apoplast, bridges the plant and fungal membranes in the space between the cells, thus preventing water and nutrients from reaching the plant’s cells, and redirecting them to nourish the fungus. The fungus continues growing, penetrating more and more plant cells, until new spore growth occurs. The process repeats every 10 – 14 days, producing numerous spores that can be spread to other parts of the same plant, or to new hosts.

Captions and Photo Credits (all Audrey Benedict):

#1. Aecidium magellanicum, commonly known as the calafate rust, is shown here as a beautiful red-leaved witches’ broom on the evergreen shrub Calafate (Berberis buxifolia).

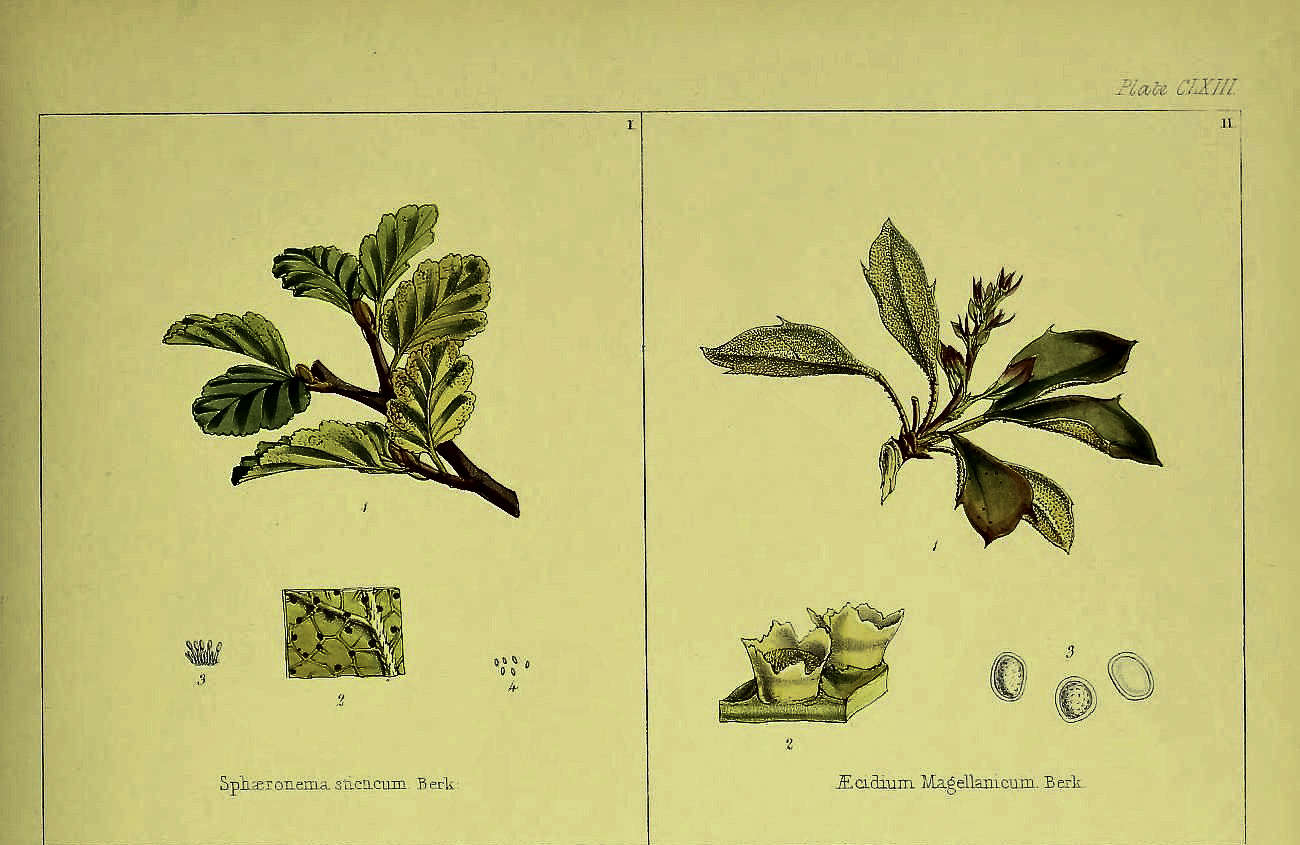

#2. Rare archival source: A jpg of Plate CLXIII of Hooker’s Flora Antarctica, Published in: Bot. Antarct. Voy. Erebus Terror 1839-1843, II, Fl. Nov.-Zeal.: 450, fig. 163:2 source: Rust Fungi. Fig I: Sphaeronema sticticum Berk.; Fig II: Aecidium Magellanicum Berk., 1847; Synonym of Puccinia magellanica (Berk.) E.K.Cash, 1972.

#3. Calafate in flower.

#4 & #5. Calafate rust witches’ brooms.

#6. A wooden model of the cellular structure of a single aecium or “cluster cup,” of Aecidium berberidis, from a collection housed at the Botanical Museum Greifswald.

click images to enlarge

click images to enlarge

To help build global awareness, we would appreciate it if you would share this post with your friends and colleagues. Please choose one of the options below which includes email and print! Thank you.

Wow, that wooden model is quiet amazing.

your images are so vivid and explain this amazing take over so perfectly.