ePostcard #116: Nightwatch: Sea Turtles Are Ecosystem Sentinels (Part 2)

ePostcard #116: Nightwatch: Sea Turtles Are Ecosystem Sentinels (Part 2)

Sea turtles are ecosystem sentinels—critical threads in the complex tapestry of global biodiversity. For sea turtle recovery efforts to succeed globally, we must ensure that the far-flung threads of a sea turtle’s existence are intact; when the oceans are healthy; and when nesting beaches, seagrass pastures, coral reefs, and migratory pathways remain safe and usable. To do this, we must fully understand each species’ unique natural history—the adaptations that attune their lives to the marine environment, their distributional patterns, migratory travels, their diet and key feeding areas, and their breeding and nesting behaviors. With the exception of the flatback sea turtle, whose distribution is largely restricted to the tropical waters of northern Australia, the other six species (leatherback, green, loggerhead, hawksbill, and the Kemp’s and olive ridleys) occur in the ice-free areas of the global ocean, including the temperate to tropical reaches of the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, the Mediterranean, and the tropical and subtropical waters of the Indian Ocean. Although the lives of sea turtles remain mysterious in many ways, the advent of remote camera traps, environmental sensors, GPS loggers and other satellite-enabled tracking equipment have greatly expanded our understanding of sea turtle migrations, as well as their behavioral ecology and physiology.

In 2003, I had the remarkable experience of paddling along a moonlit beach in Tortuguero National Park with a group of turtle protection volunteers from the village of Tortuguero. Tortuguero National Park, which lies on the northeastern Caribbean coast of Costa Rica, is the most important nesting site for the endangered green sea turtle (photo #2) in the Western Hemisphere and hosts one of the two largest green turtle populations on Earth. The region was protected as a nesting sanctuary in 1963 and declared a National Park in 1970, largely due to the efforts of legendary turtle biologist Archie Carr and his Caribbean Conservation Corporation. It was the beginning of the nesting season for green sea turtles and our task was to scan the beaches at Playa Tortuguero for the fresh, tractor-like trails made by nesting females as they emerge from the sea to lay a clutch of eggs. It was a clear night and I rejoiced in the light-gathering capability of my binoculars, but there were no turtles or tracks to be seen. After several hours floating silently along in the velvet darkness, we paddled to an area that was normally off-limits to check for nesting activity there. Suddenly, the lion-like roars of mantled howler monkeys reverberated across the water. Were they harassing a potential predator or responding to a territorial infringement by other howler monkeys? I never imagined that jaguars might kill and eat turtles. What I soon learned from our biologist guide was that the howlers were most likely harassing a jaguar, an increasingly common predator of sea turtles on the nesting beaches at Tortuguero (see photo #3).

Wherever tropical forests come in contact with beaches in the Americas, jaguars have probably been preying on nesting sea turtles for millennia. This juxtaposition poses an unusual challenge for conservation biologists because sea turtles and jaguars are ecosystem sentinels and are also protected in their respective habitats. The first reports of jaguar predation on sea turtles in Central America came from Costa Rica in the 1980s, specifically in Tortuguero National Park and Pacuare Nature Reserve. During the breeding season for sea turtles, lone jaguars patrol the beaches at night in search of nesting sea turtles. When the jaguar discovers a nesting sea turtle, it usually attacks with a crushing bite to the head or neck that kills the turtle instantly.

To determine how much jaguar predation the sea turtles could sustain, SWOT (State of the World’s Sea Turtles) researchers Luis Fonseca, Ian Thomson and their colleagues conducted a 10-year study (2010–2020) using infrared camera traps to document the deadly nighttime interactions between these two ecosystem sentinels, at Tortuguero and at the Guanacaste Conservation Area, which is located on Costa Rica’s Pacific Northwest coast. Guanacaste includes a 68-mile stretch of coastline with nine sandy beaches, including Nancite Beach, one of only a handful of sites worldwide where olive ridleys come ashore in the mass nesting events known as arribadas (photo #4). Beginning in 2010, at Nancite Beach, which is less than 0.6 miles long, the researchers reported that jaguars kill between 20 and 50 sea turtles a year, and the project identified around 20 individual jaguars. This may seem a stunning number of jaguars, but the actual number of turtles killed represents less than 1 percent of the local nesting population. Between 2014 and 2019, an average of 37,000 sea turtles nested annually, but jaguars killed only 140. As you might imagine, high on my naturalist’s wish list is a visit to Playa Nancite and the chance to see thousands of female olive ridley turtles coming ashore in an arribada—and, yes, catching a glimpse of a jaguar on patrol is also on the list!

With the majority of their lives spent underwater, sea turtles reveal their secrets slowly. These ocean nomads come ashore only to rest when necessary, bask in the sun, and most importantly, to nest. Unlike their freshwater relatives, the head and limbs of sea turtles are fixed outside the shell and cannot retract into the shell. This distinctive feature, along with a streamlined shell, makes them more hydrodynamic in the water than their land-based counterparts, and allows them to maneuver easily through their ocean realm (photos #’s 5 & 6). To help them efficiently power their bodies through water, sea turtles have long flippers instead of the webbed feet of their freshwater counterparts. The large and strong front flippers act like paddles to propel them through the water, while the smaller back flippers function as rudders to help them steer. In females, the hind flippers have another purpose as well—they are used with deft precision to dig an egg incubation chamber in the sand. Sea turtles mate at sea, usually quite close to where the females will go to shore to nest. Their flipper-powered gracefulness underwater, especially during mating, reveals a beauty denied them during their brief times on land.

The largest living sea turtle, the leatherback (photos #’s 7 & 8), provides us with a stunning example of sea turtle diversity and adaptation. Paleontologists believe that the leatherback is the sole survivor of a primitive order that resembled the first sea turtles. Describing leatherback biology is couched in superlatives: they are the biggest reptiles in the world, with the largest measuring at least 8 feet in length and weighing in at more than a ton. Leatherbacks are also the deepest-diving sea turtles, capable of reaching depths of 3,000 feet, and are unique among reptiles in being able to regulate their body temperature. One of their most fascinating adaptations has to do with their favorite food—jellyfish. As you can imagine, jellyfish don’t go down the gullet without a fight (see photo #9). The leatherback’s esophagus is lined with cartilaginous papillae, sharp, keratinized prongs that grab the slippery jellyfish and force it down into the stomach and keep the turtle from being injured by the stinging cells of its prey. Jellyfish are primarily water, a little protein, some vitamins and minerals, and some fat. How does the leatherback fuel its migratory journey eating jellyfish? Another adaptation! They have an extremely long esophagus that leads from the mouth to the rear of the body, and then it loops up the side again until it reaches the stomach. This long esophagus acts as a holding pouch so that the leatherback can continually digest its food – as parts of its meal leaves the stomach digested, new jellyfish are being pushed into the stomach.

When sea turtles are not nesting, they make incredibly long migrations between feeding and breeding areas, spending different parts of their long lives in various parts of the world. The multiyear, epic migrations of sea turtles involve some of the most remarkable feats of orientation and navigation in the animal kingdom. Adult turtles of several species migrate across hundreds or thousands of miles of open ocean to nest on or very near the beaches where they hatched, which are often located in some of the most remote places on Earth. Leatherbacks, for example, travel an average of 3,700 miles each way. Sea turtle migrations are all the more astonishing in view of the fact that they are accomplished in an open-ocean environment devoid of visual landmarks and by marine animals whose poor eyesight above water probably precludes the use of star patterns and other celestial cues. As hatchlings, turtles that have never been in the ocean before establish unerring courses towards the open sea as soon as they enter the water and then maintain their headings after swimming beyond sight of land. The “onboard” mechanisms that enable sea turtles to navigate the open ocean and to locate their natal beaches have mystified scientists for more than 50 years. While earlier studies showed that sea turtles use the Earth’s magnetic field as part of their navigation system in the open ocean, it remained unclear whether adult turtles also depended on magnetic features to recognize and return to the nesting sites where they were born.

Scientists know that sea turtles use magnetic features and a variety of other cues to navigate the oceans. Depending on the specific location on earth, the magnetic field has a specific inclination and intensity. Sea turtles can perceive both the magnetic field’s intensity and its inclination angle, the angle that the field lines make with respect to the Earth’s surface, as a distinctive magnetic “signature.” Recent research has shown that sea turtles likely “imprint” on the magnetic signature of their natal beach, through a process called geomagnetic imprinting, at a very young age or even before they hatch. This magnetic signature acts like a compass for them, even as they travel hugely long distances from their natal beaches—returning a couple decades later, as breeding age adults, to lay their eggs on the same beaches where they hatched.

But how do adult sea turtles know when to migrate? Recent research reported in the Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, suggests that leatherback sea turtles may be able to sense seasonal changes in sunlight by means of an un-pigmented spot on the crown of their head—known as the pink spot (see photo #12). Researchers examined the anatomical structures beneath the pink spot and found that the layers of bone and cartilage were remarkably thinner than in other areas of the skull. This thin region of the skull allows the passage of light through to an area of the brain, called the pineal gland, that acts as biological clock, regulating night-day cycles and seasonal patterns of behavior. The researchers suggest that the lack of pigment in the crowning pink spot and thin skull region underlying it act as a “skylight,” allowing the turtles to sense the subtle changes in sunlight that accompany changing seasons, signaling them to return south when autumn approaches.

Photo, Credits and Captions:

#1. Photo Credit (top of page): Courtesy of Juan Manuel Gonzalez.

Caption: This magnificent photograph shows a female “black” sea turtle (Chelonia mydas agassizi, a color morph of the East Pacific green) digging her nest on moonlit Colola Beach, a key nesting area for the subspecies on Mexico’s Pacific Coast. Populations of the black sea turtle were once thought to be beyond recovery by some researchers, but a stunning success story has brought them back to nest again on Colola Beach along Mexico’s Pacific Coast. From tens of thousands of nests in the 50’s and 60’s, their numbers dropped to just 533 in 1999. The sea turtles nesting at Colola Beach were nearly gone. This astounding population recovery story is due, in no small part, to the efforts of children from the local indigenous Nahua community. The kids had been recruited to participate in a unique sea turtle protection partnership with researchers from the University of Michoacan. Over twenty years of effort, the Nahua community had stopped eating turtles and their eggs and exporting them out of the community. Nesting numbers started rising. The hatchlings that were saved in the 80’s began to return as adults. Throughout the next decade, the number of nests rose to between 3,000 and 8,000 per year (160,000 – 560,000 hatchlings each season). Nesting at the beach went from nearly 10,000 nests and 650,000 hatchlings in 2010, to more than 45,000 nests and 2 million hatchlings in 2019. That represents a more than 8,000% increase over 20 years, which makes Colola one of the world’s most successful sea turtle conservation efforts. The community and university responsible for these efforts won the Champions Award from the International Sea Turtle Society in 2018.

click images to enlarge

#2. Photo Credit: Courtesy of the Sea Turtle Conservancy and Standard Fruit Co.

Caption: A green sea turtle has just finished nesting and is headed back to the sea at Tortuguero, Costa Rica. Tortuguero hosts more than 100,000 nests each year, making it one of the largest green turtle nesting sites in the world. The conservation and research program at this site was initiated by Dr. Archie Carr and has been carried out continuously by the Sea Turtle Conservancy since 1959, making it the longest-running and one of the most iconic sea turtle conservation initiatives in the world.

#3. Photo Credit: Courtesy of © Ian Thomson and State of the World’s Turtles (SWOT; seaturtlestatus.org)

Caption: SWOT camera traps have allowed researchers to study interactions between jaguars and sea turtles along protected, jungle-lined beaches in Costa Rica. This encounter between a jaguar and a green turtle was captured in Tortuguero National Park on Costa Rica’s Caribbean coast.

#4. Photo Credit: Courtesy of Thomas Peschak/National Geographic.

Caption: Costa Rica’s Pacific coast is home to two olive ridley mass nesting (arribada) beaches: Nancite and Ostional. The beaches are among a mere half-dozen such sites found worldwide, Once or twice a month during Costa Rica’s rainy season, female olive ridley sea turtles come ashore by the tens of thousands and lay eggs in a mass nesting (arribada) event. Hatchlings begin emerging about 45 days later.

#5. Photo Credit: Courtesy of NASA/Kim Shiflett.

Caption: Green sea turtles are among the two most common species found on Florida’s “Space Coast.” The other is the loggerhead, which is listed as threatened. Note the metal tag, which records the location of this young green turtle’s natal beach.

#6. Photo Credit: Courtesy of Daniel Clark/USFWS (Midway Atoll).

Caption: These Hawaiian green sea turtles are resting or basking, but do not nest on Midway Atoll. More than 90% of the Hawaiian green turtle population nests at French Frigate Shoals, a cluster of sand islets located in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. Nesting occurs from late April through September with a peak in June-July. Each female deposits 1-5 egg clutches (average 1-2) at 11-18 day intervals.

#7. Photo Credit: Courtesy of Jimmy Golian to Florida Today (May 21, 2020).

Caption: This massive female leatherback sea turtle, weighing in at an estimated 800 pounds, decided to dig her nest along the Indiatlantic Boardwalk in Melbourne Beach, Florida. Leatherback’s are the world’s largest turtles, averaging 6 feet length and weighing anywhere from 500 to 1,500 pounds, according to the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. She had a tag on her left front flipper (she had lost her right rear flipper sometime before being tagged the first time in 2016). This tag allowed researchers to report that she had nested in Juno Beach in 2016 and had nested there again one month before arriving in Melbourne.

#8. Photo Credit: Courtesy of the Sea Turtle Conservancy and Standard Fruit Co.

Caption: A nesting Tortuguero leatherback returns to the sea.

#9. Photo Credit: Courtesy Black River Outdoors.

Caption: Leatherbacks eat a diet of almost exclusively jellyfish, with cannonball jellyfish being their primary food source during their migration north from the Caribbean. They require huge amounts of jellyfish to support their enormous size. The mouth of a Leatherback looks like something from a horror movie. Their mouths and esophagus are filled with long, sharp spikes made of cartilage. These prongs keep jellyfish from floating out when the turtles expel excess sea water that they have swallowed. The long esophagus lets them eat large quantities of jellyfish very quickly.

#10. Photo Credit: Courtesy of Richard Carey and bioGraphic.

Caption: As adults, green sea turtles eat a mostly herbivorous diet, grazing on algae and pruning sea grass beds like underwater gardeners. However, juveniles often prey on invertebrates, including easy-to-nab jellyfish (the thick-skinned turtles appear to be immune to the stinging tentacles of even the most venomous species). Here in the cerulean waters off the coast of Thailand’s Similan Islands, a young green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas) stands guard over the tufted bell of a mosaic jellyfish (Thysanostoma thysanura). Its first few hungry nips at the gelatinous prey have altered the jelly’s buoyancy, forcing the turtle to cradle its meal with its flippers lest it sink to the bottom.

#11. Photo Credit: Courtesy of Dr. Heather Harris/Upwell.org).

Caption: Dr. Heather Harris, a wildlife veterinarian, is one of the driving forces behind Upwell’s new ecosystem health program. The aim of this program is to better understand specific environmental threats that present health risks to sea turtles. All too often, sea turtles mistake plastic bags for their intended jellyfish prey, which can lead to a litany of sometimes-fatal health problems, from gut blockages to developmental delays.

#12. Photo Credit: Courtesy of Dr. Heather Harris/Upwell).

Caption: Mac (her nesting survey name) is a rare daytime nester at Juno Beach, Florida and appears to be emaciated. Dr. Harris noted Mac’s sunken neck and shoulders and the prominent dorsal ridges of her carapace. The fatty blubber layer, which normally provides the energy and insulation that enables leatherbacks to thrive in cold temperate water, unlike their hard-shelled cousins, is poorly developed and suggests that food availability was poor along her migratory route. Upwell’s mission (as a nonprofit) is to protect endangered sea turtles by reducing threats at sea, including fisheries bycatch, ship strikes, pollution, climate change and other detrimental human activities.

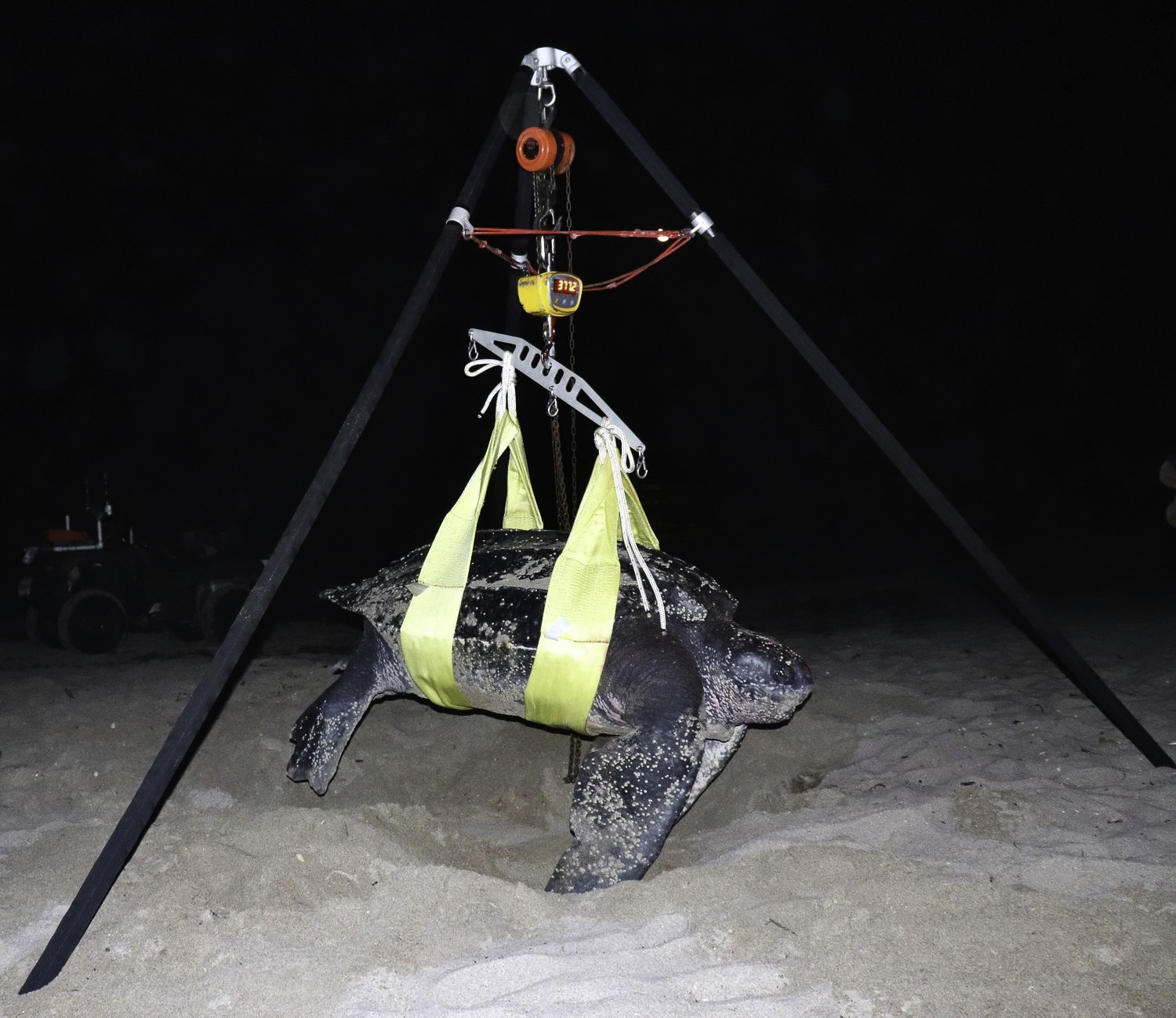

#13. Photo Credit: Courtesy of Dr. Heather Harris/Upwell.org.

Caption: This leatherback turtle is suspended from a tripod to obtain her body weight. This healthy and robust female leatherback weighs 814 lbs.

click images to enlarge

To help build global awareness, we would appreciate it if you would share this post with your friends and colleagues. Please choose one of the options below which includes email and print! Thank you.

#116 underwent a long gestation, and it emerged very well developed and powerful for a post card. I suspect a born writer is hatching some plans…

Many of my readers, like Don, have noticed the lulls between ePostcards. The primary reason for this, other than the fact that daily life sometimes intervenes, is that I do a tremendous amount of reading and research in the scientific literature to educate and update myself first on any topic. As a writer, this process allows me choose a few of the most fascinating advances (to me) in our understanding of the natural world to share with my readers. For those without the time to read long blogs, I try to make the photo captions serve as “stand alone” bits of information. Despite the fact that Clyde, our website mastermind, has made the ePostcards also work on a iPhone or other mobile device, I would strongly suggest a laptop or desktop computer. Remember to click on each image to enlarge it for its visual power!

Audrey another absolutely facinating blog read. I am a slow reader, but enjoyed all the time needed to read and retain( that is another story). Thank you for all the time you spend to give us the gem of your research.

I can picture you paddling in your single kayak at midnight with your trusty binac, looking for the nest sites and more! Thank you for allowing to share on social media.