ePostcard #120: A Flipper of Hope

Photo Credit: Courtesy of Tim Briggs, Northeastern University (Marine Biology), and the online journal Massive Science. (Green sea turtle, San Diego Bay)

If there is danger in the human trajectory, it is not so much

In the survival of our own species as in the fulfillment of the

ultimate irony of organic evolution: that in the instant of

achieving self-understanding through the mind of man, life

has doomed its most beautiful creations.

—E. O. Wilson

In the midst of the pandemic, I had a conversation with my favorite young naturalist, 7-year old Nash Fransen, who asked me a question that I felt I had to answer honestly but as gently as possible. His question surprised me because it correctly linked dinosaurs to extinction, and he wanted to know why those huge animals had disappeared—and if they would ever come back. How do you tell a child, for whom billions and millions of years mean nothing in the context of their own brief existence, that there have been five great mass extinctions during the history of life on Earth. How do you explain the devastation at the end of the Permian, some 250 million years ago, which is sometimes referred to as “the great dying.” or the most recent mass extinction at the close of the Mesozoic Era—the Cretaceous–Paleogene Extinction—when a monstrous asteroid hit the Earth and wiped out the nonavian dinosaurs and at least 75% of life on our planet?

What troubled me the most was how to tell Nash, without frightening him, that most scientists believe we are in the midst of a sixth extinction crisis of our own making—the Anthropocene. As Nash waited patiently for my answer, I was reminded of the subtitle of Carl Safina’s extraordinary book, “Voyage of the Turtle: In Pursuit of the Last Dinosaur.” The centerpiece of Safina’s natural history narrative is the leatherback sea turtle, a species that traces its evolutionary lineage back more than 100 million years—the closest thing we have to a living dinosaur. I decided that introducing Nash to the wondrous lives of sea turtles might provide “a flipper of hope” about life enduring against incredible odds. In the Anthropocene, extinction is only inevitable if we fail to take action. Mentoring and sharing the wonders of the natural world with others and, yes, with our youngest naturalists, may be one of our most important roles as Earth’s stewards.

click images to enlarge

#2. Photo Credit: Steve Winter and SeaTurtleWeek (seaturtleweek.com and seeturtles.org)

When my view of what is happening in the natural world darkens,

I often transport myself to a moonlit sea turtle nesting beach—and take a deep breath.

BORDER CROSSINGS

Glittering in a wash of golden moonlight, a female olive ridley makes her way back out to sea after laying her eggs on La Flor Beach. Located on the Pacific coast of Nicaragua, La Flor Wildlife Refuge is one of only nine olive ridley arribada sites in the world. Thousands of female ridleys converge here every year between July and December to dig nests along this horseshoe-shaped beach and lay their eggs. On a beautiful evening, this lone female appears to have this stretch of beach to herself. She moves slowly and purposefully towards an ocean that spreads into black infinity—she’s heading home. We can only hope that the local hueveros (turtle egg gatherers) were discouraged by the rangers from digging up her freshly laid eggs. Despite environmental laws and protections, Nicaragua’s beaches, much like those in Mexico and in all Central American countries, are subject to rampant egg poaching timed to take advantage of the turtle nesting season.

Conservation is a global responsibility. How do we successfully protect sea turtles whose life histories cross international waters, geopolitical boundaries, and legal jurisdictions? There are no easy answers. With human populations growing exponentially, and with the corresponding increases in land development, pollution, and resource depletion, achieving coordinated conservation action among nations remains an elusive goal. The IUCN Marine Turtle Specialist Group has identified five major threats to sea turtles worldwide: direct harvest for their meat, eggs and ornamental shells, coastal development and habitat loss, fisheries bycatch, marine pollution, and climate change. These threats face all seven sea turtle species at every life stage, but I would also add a sixth to the list in many parts of their range—the cascading impacts of poverty in places where humanitarian crises are increasingly common.

Photo Credit: Courtesy of Coastal Care (coastalcare.org) and Kansas Sebastian. Olive ridley eggs (the bags of sand-dappled eggs/huevo) for sale in a Mexican market. Despite anti-poaching regulations, millions of sea turtle eggs are taken each year by poachers and sold on the black market for much-needed income in countries where poverty has reached pandemic levels.

With beaches on both the Atlantic and Pacific Coasts, the ocean is at the center of life for Nicaraguans born and raised in the communities next to these turquoise waters, and sea turtles are an integral part of it. Nicaragua’s beaches provide crucially important nesting habitat for hawksbill, leatherback and olive ridley turtles. Turtles are a national symbol, and appear on some of the country’s banknotes. Sadly, forty years after Daniel Ortega ousted the Somoza dictatorship, Nicaragua remains one of the poorest countries in Latin America. In 2018, in response to nationwide nonviolent protests against the government, President Ortega launched a campaign of violent repression against all political and social opposition. A report published at the end of 2019 estimates that roughly a third of the Nicaraguan population, or more than two million people, now live on less than $1.76 per day. Ortega’s actions forced thousands of Nicaraguans to flee, joining fellow refugees from neighboring El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. When Trump was railing against the flood of refugees headed north in 2018—the caravans populated with “murderers and rapists” in Trump’s nativist diatribe—you were witnessing the tragedy of Latin American people pushed to their limits, either by political repression or gang violence.

The half-hearted conservation efforts by President Ortega’s authoritarian regime have done little to mitigate Nicaragua’s ongoing biodiversity crisis. Before the crackdown in 2018, the Ministry of the Environment briefly implemented a program, now defunct, to allow a limited turtle egg harvest. The objective was to encourage communities to protect the beaches and ensure optimal conditions for the turtles to lay eggs. In exchange, community members would receive a percentage of the eggs after the arribadas had finished. During the turtle nesting season, prior to the 2018, the army and the Ministry of the Environment and Natural Resources (MARENA) provided limited assistance to the rangers guarding the beach at La Flor Wildlife Refuge. The deployment of these forces to address the political unrest left the refuge unprotected. Residents took advantage of the absence of soldiers and park rangers to go into the ocean and intercept shore-bound turtles. Paso Pacífico staff members reported that around 1,000 people came to the beach and raided some 2,000 nests during one week of the arribada, and also killed at least six turtles for meat and eggs.

What does this have to do with sea turtle conservation efforts across international borders? To answer this question, I highlight the work of an outstanding Nicaragua-based conservation nonprofit—Paso Pacífico. This organization has persevered and continues to focus their efforts on transboundary sea turtle protection, educational outreach, and developing economic incentives in the struggling communities where they work. Do they risk being shut down or expelled? Yes, they certainly do. Several Nicaraguan conservationists, in fact, have been murdered for their efforts. Culturally, sea turtle eggs have long been a food source for communities living around the protected areas and nesting beaches throughout Central America. As is true for many countries in the world where extreme poverty is the common denominator for illegal activities, conservation action is quickly abandoned in the face of human misery.

PASO PACÍFICO

Photo Credits: All photographs in this section courtesy of Paso Pacífico and its founder, and director Dr. Sarah Otterstrom, Liza González, the Nicaraguan-based head of Paso Pacífico, Monica Pelliccia, and conservation scientist Dr. Kim Williams-Guillén.

Paso Pacífico, a nonprofit research and conservation organization founded in 2005 (with offices in California, Nicaragua, and El Salvador), focuses its efforts on Mesoamerica’s Pacific Slope with the longterm goal of connecting land and sea through a regional network of biological corridors, In Nicaragua their efforts are centered on the Paso del Istmo biological corridor, the strip of land that sits between Lake Nicaragua and the Pacific Ocean. Its founder and executive director, Dr. Sarah Otterstrom, a conservation scientist with over 20 years of experience in Central America, has dedicated her career to protecting the region’s tropical dry forests and Pacific coast habitats. The organization’s success comes from recognizing the need for collaborative and inclusive conservation efforts that enable community members to make their own livelihood choices more environmentally, economically and socially sustainable.

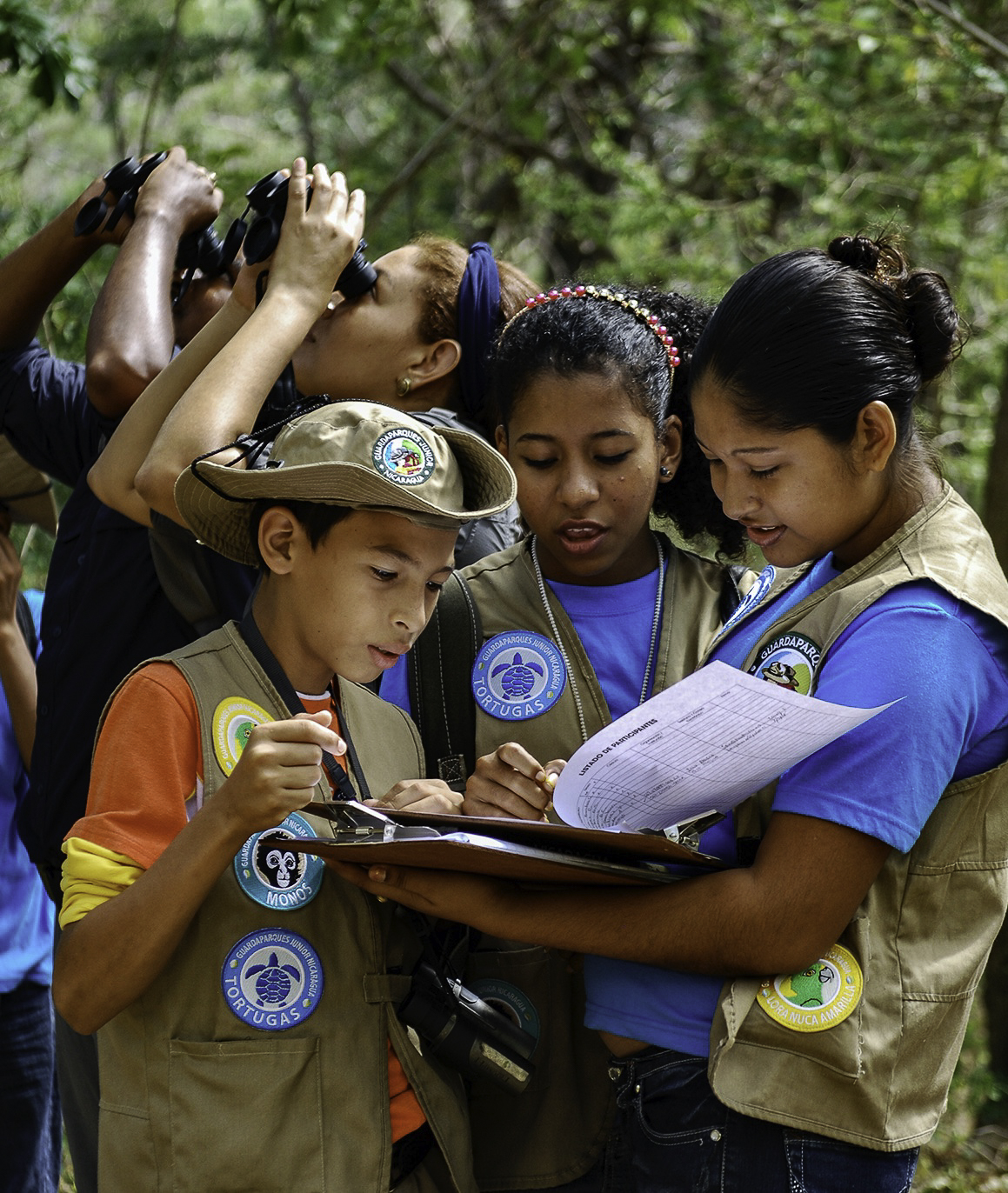

Educational outreach plays a key role in Paso Pacífico’s approach to preserving Nicaragua’s biodiversity. In 2012, they launched the Junior Ranger program for children ages eight to thirteen. This rigorous program uses engaging classroom instruction, experiential field trips, and community service projects to teach principles of biology, ecology, and environmental citizenship. After school and on weekends, these children learn about and come face to face with sea turtles, endangered monkeys, plastic pollution, mangroves, and more. To date, over 400 Junior Rangers have graduated! The life-changing experiences they have gained from this program are helping them be better stewards of nature and better members of their communities. They share what they learn with their families and friends, and many Junior Rangers continue to stay involved with the program and help mentor younger children.

How do you catch an egg thief? By building a tracking device that looks like an egg and fools the thief. Paso Pacífico-affiliated scientist Dr. Kim Williams-Guillén initially conceived and designed the decoy eggs in response to a call for proposals from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) for the Wildlife Crime Tech Challenge. They were looking for projects using technological advances to fight wildlife poaching. Paso Pacifico’s decoy turtle egg—the InvestEGGator—began with Dr. Williams-Guillén designing the eggshell on her computer. Thanks to a 3-D printer, she was able to replicate the shape of a sea turtle egg out of a soft type of plastic. Getting the egg shell texture right was tricky. With the help of a special effects makeup artist from Hollywood, Lauren Wilde, they first coated the eggs with waterproof glue to protect the hardware inside and then perfected the right shade of paint and texture to make the egg look realistic. A lightweight GPS tracking device fits neatly inside the decoy egg.

Paso Pacífico, working in collaboration with researcher Dr. Helen Pheasey and her colleagues at the University of Kent, tested the InvestEGGator on several nesting beaches in Costa Rica. Working in the middle of the night, researchers buried the decoy eggs in nests along with the real eggs, covered their tracks on the beach, and waited. Inside each egg, a GPS device was ready to track the movements of poachers. The study was published in the journal Current Biology in 2020 (see the citation below). “Our research showed that placing a decoy into a turtle nest did not damage the incubating embryos and that the decoys work,” says lead author Helen Pheasey. “We showed that it was possible to track illegally removed eggs from beach to end consumer. From a law enforcement perspective, the critical thing is to identify those who are trafficking and selling the eggs, often door to door.”

Now, back in Ventura, Paso Pacífico is working with a local California company, True Parts Manufacturing, and a San Diego engineering firm, to improve the decoy egg. They’re trying to reduce the decoy’s cost and improve the design, including a longer-lasting GPS battery. The researchers say they’d like to see more sea turtle conservation projects using the decoys on their nesting beaches. Such efforts could potentially shed light on differences in the turtle egg trade in different countries. In addition to continuing to improve the technology and its deployment, they’re also interested in expanding the technology to other species—for example, Paso Pacifico plans to work with Costa Rican scientists to adapt the transmitter for use in tracking shipments of shark fins. They are also considering its use in tracking the theft of eggs from parrot nests.

You see—there is reason for HOPE!

Source: Current Biology, Pheasey et al.: “Using GPS enabled decoy turtle eggs to track illegal trade” https://www.cell.com/current-biology/fulltext/S0960-9822(20)31255-0 DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2020.08.065

click images to enlarge

To help build global awareness, we would appreciate it if you would share this post with your friends and colleagues. Please choose one of the options below which includes email and print! Thank you.

Beautiful. Thank you for this ray of sunshine and hope!