ePostcard #122: Fisheries Bycatch

Photo Credit: Courtesy of NOAA.

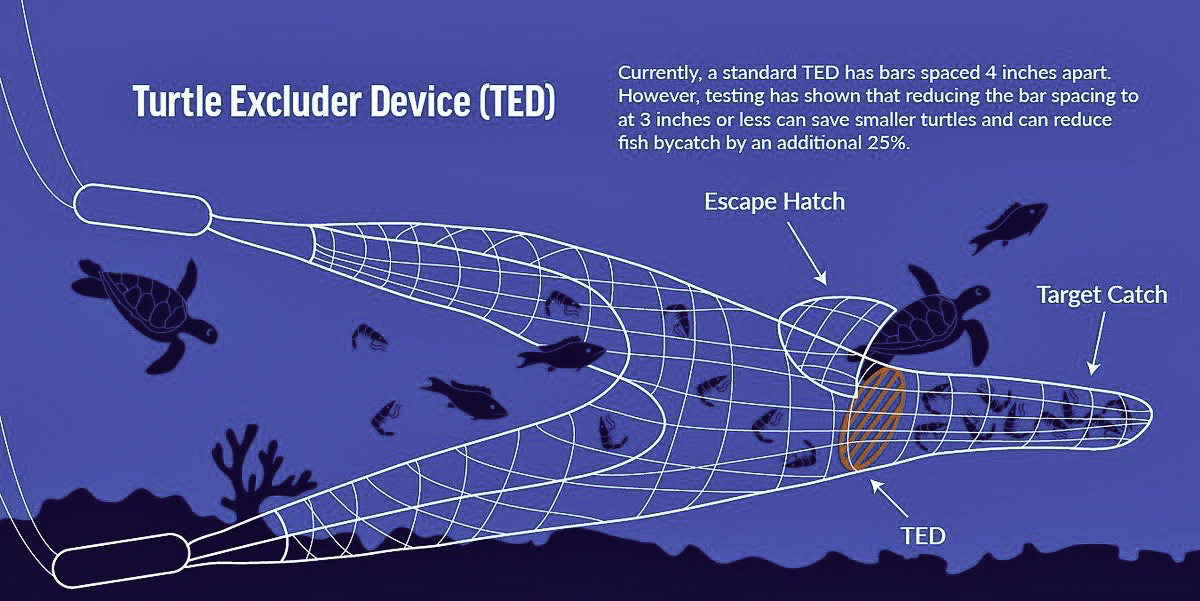

A juvenile loggerhead sea turtle escapes a trawler net that has been quipped with a Turtle Excluder Device (TED). These sea turtle “escape hatches” were originally developed to benefit both the commercial shrimp fishery and the marine environment. Prior to TEDs, an estimated 44,000 loggerheads died each year in commercial fishing gear in the Northwest Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico, more than ten times current numbers.

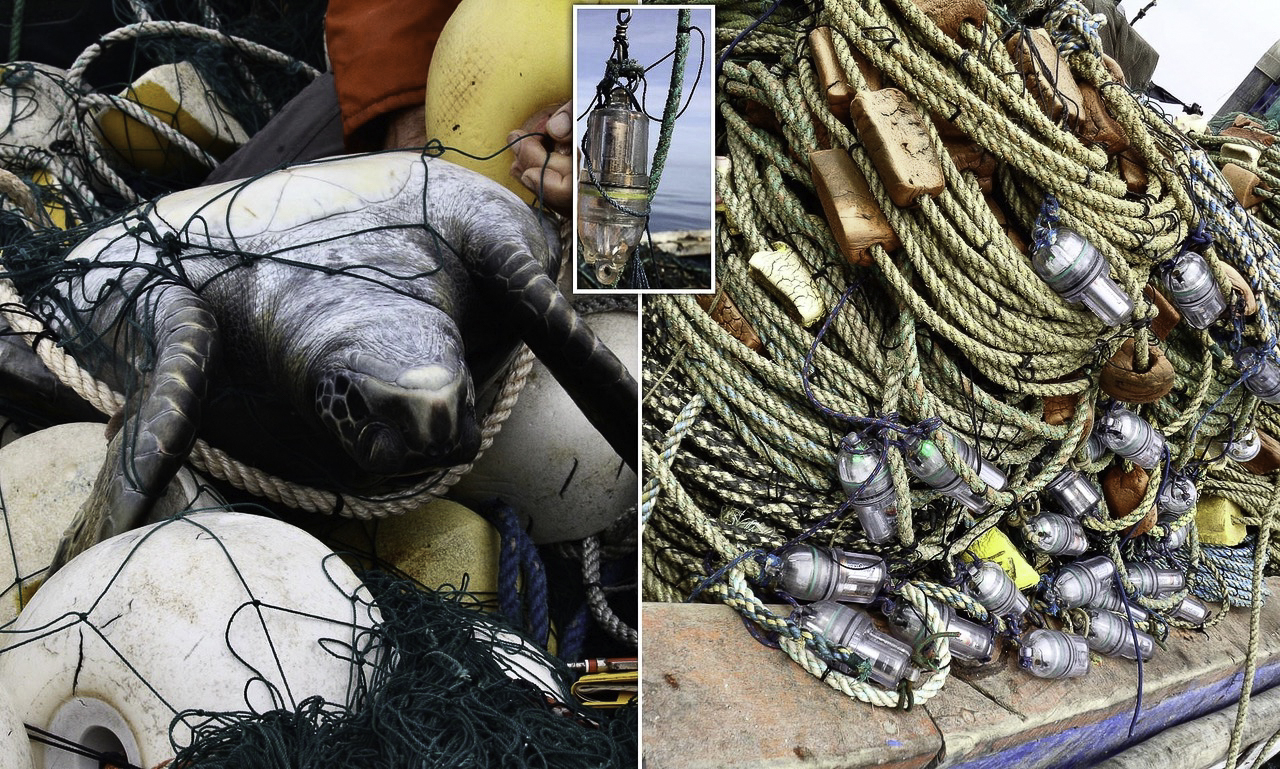

Photo Credit: Courtesy of Nation Swell and Monica Humphries.

Adult sea turtles have few natural predators — unless you factor in human beings. The leading cause of sea turtle mortality worldwide has been their unintentional capture—called bycatch—by three commercial fisheries: shrimp trawling, gillnetting, and longline fishing. Global estimates of the annual capture, injury and mortality of adult and juvenile turtles are staggering — 150,000 turtles of all species killed in shrimp trawls, more than 200,000 loggerheads and 50,000 leatherbacks captured, injured or killed by longline hook fisheries. The numbers of all turtle species drowned in gillnets may well exceed those of trawl and longline fisheries combined because these nets are used by countless numbers of local fishermen in tropical waters around the world. Those sea turtles that manage to escape from fishery gear on their own are often left with amputated flippers, large hooks lodged in their bodies, and other debilitating injuries. With nearly all sea turtle species endangered, it has become a priority for scientists and conservationists to find solutions to reduce sea turtle bycatch.

The bycatch of sea turtles and other “non-target” species that are not sought for human consumption is a complex global issue that threatens the sustainability and resiliency of our fishing communities, economies, and the marine ecosystems we all depend on. Approximately 40% of all the animals caught in these three commercial fisheries are actually non-target bycatch, a biodiverse group that includes invertebrates, fishes, marine mammals, sea turtles, and seabirds. For protected species, such as sea turtles, albatrosses and many marine mammals, bycatch remains a significant threat to the recovery of at risk populations worldwide.

click images to enlarge

The global proliferation of both industrially-mechanized and small-scale commercial fisheries in areas where sea turtles concentrate their foraging activities during their yearly migrations clearly plays a central role in their mortality. Sea turtles cannot breathe underwater, but they can hold their breath for long periods of time—between 4 to 7 hours when resting. While holding their breath, their heart rate slows significantly to conserve oxygen—up to 9 minutes can pass between heartbeats. Because of this, sea turtles can stay underwater for an extended period of time when not stressed. When actively swimming or foraging, however, sea turtles must surface periodically to breathe. If they are forcibly submerged by fishing gear for more than about 90 minutes, their blood oxygen falls to essentially zero and they drown in the net or on the hook. Even after a submergence of only 30 minutes or so, a sea turtle’s blood can remain dangerously acidic for more than 10 hours. It will die if it is immediately released back into the sea before recovering from the physiological consequences of its entrapment.

Photo Credit: Tom Doeppner, Wikimedia Commons. This is a closeup of a hawksbill turtle.

What attracts the sea turtles to the nets and other fishing gear? Sea turtles rely primarily on visual cues in searching for food. Within the eye, cells called rods detect movement in dim light conditions and cells called cones detect colored light. Animals that see well in the dark tend to have more rods than cones. Another trait that enables some animals to see well in dim light are large eyes with large pupils. Sea turtles have fairly evenly distributed rods and cones and their eyes are small in comparison to their body size. They see best in bright light. So, how do they feed at depth or at night when light is limited? Sea turtles might very well be relying on their ability to see bioluminescence. The pupil of a sea turtle’s eye is large enough to detect the point-source light of bioluminescent prey, and turtles likely track this glow to locate food items.

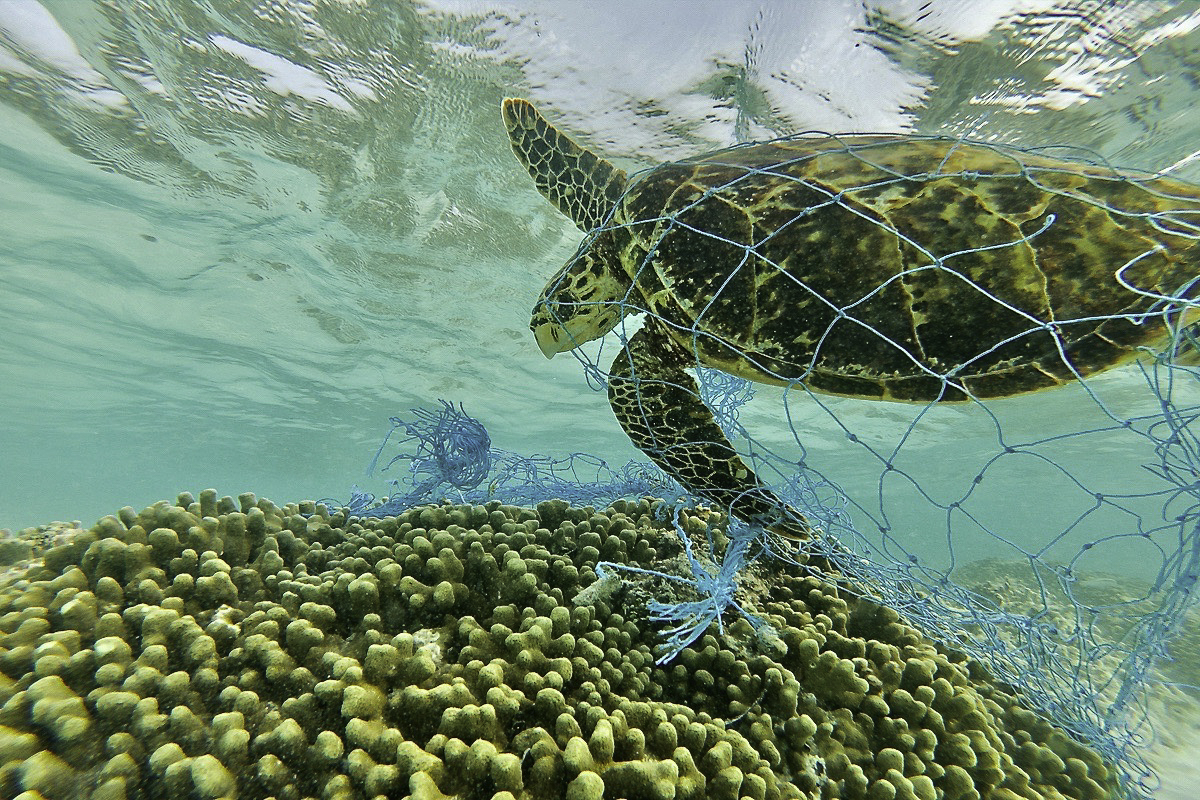

Photo Credit: Courtesy of Healthy Seas (healthy seas.org). A leatherback sea turtle bound up in derelict (or ghost) fishing gear.

“Ghost gear” refers to any fishing gear that is lost, abandoned or purposely discarded at sea. This includes fishing nets, longlines, fish traps, crab/lobster pots or any other human-made device used to catch fish, shrimp, crabs, and lobsters. All fishing gear is designed to efficiently catch or entrap so-called “target species,” and it can continue to do so long after the gear is lost or discarded in the ocean. When lost or abandoned fishing gear keeps on catching and killing fish, the phenomenon is called “ghost fishing.” Globally, about 6.4 million tons of derelict fishing gear — “ghost gear” — end up in our oceans each year. Injuries and deaths associated with discarded fishing gear, plastic ingestion, and fouling from gas and other petroleum products associated with commercial fisheries are on the rise.

Ghost gear pollutes the ocean, threatens marine ecosystems and and impacts the sustainability of our fisheries worldwide. Conservative estimates suggest that 640,000 to 800,000 tons of fishing gear is lost annually worldwide, which could account for at least 10% of all plastic pollution and perhaps as much as 70% of all macro plastic pollution in the global ocean. Recent studies show that ghost gear is four times more likely to harm marine life through entanglement than all other forms of marine debris combined. In the infamous Great Pacific Garbage Patch, an estimated 46% of the garbage consists of ghost gear and fishing related plastics. Fishing nets account for about 1% of the total mass of all marine macroplastics larger than about 8 inches, and plastic fishing gear constitutes over two-thirds of the total mass.

Photo Credits: Both photographs courtesy of Ocean Voyages Institute.

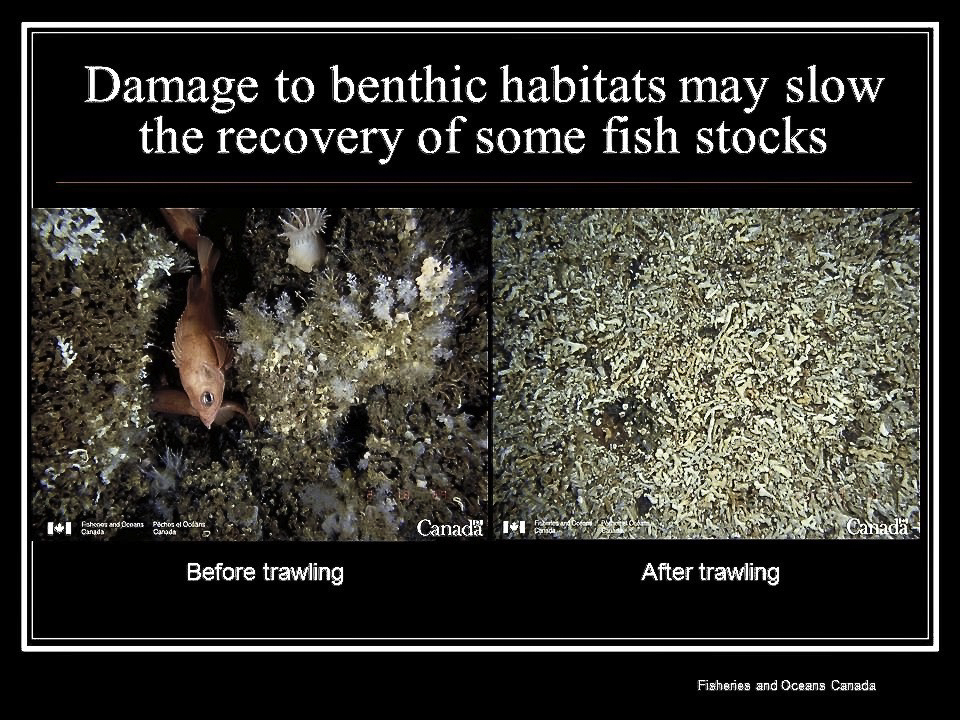

Photo Credit & Source: Courtesy of The Fish Site (thefishsite.com), and the research article “Global analysis of depletion and recovery of seabed biota after bottom trawling disturbance.” PNAS (Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, first published July 17, 2017); https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1618858114.

Bottom trawling is the most widespread source of physical disturbance to seafloor ecosystems. The vessel shown above is a relatively small bottom trawler when compared to the industrial scale trawlers that also ply the oceans. According to the global study cited above, bottom trawling removes an average of 41% of the benthic biota per pass.

Photo Credit (above): Courtesy of photographer Ricardo Braham and sevenseasmedia.org (ricardo-braham-xYVRzube0iM-unsplash.jpg). This unusual photo shows a group of juvenile sea turtles foraging together along the seafloor. You can easily imagine their vulnerability to bottom trawling gear.

Bottom trawling involves dragging heavy nets, large metal doors and chains over the seafloor to catch fish and shellfish. The trawling gear essentially destroys the existing seabed habitat by rototilling or scraping the substrate, which eliminates bottom-dwelling plants and animals that play a vital role in the marine food web. Species diversity and habitat complexity are directly affected by any changes to the physical environment. Depending on the type of trawler gear, the depth of penetration, water depth and substrate composition, it can take anywhere from 2-7 years for these ecosystems to recover.

Shrimp trawling remains one of the most significant threats facing sea turtles worldwide, with annual bycatch deaths of juvenile and adult turtles numbering in the tens of thousands. In U.S. coastal waters, loggerheads are caught in shrimp trawls in greater numbers than other species, but Kemp’s ridleys, greens, leatherbacks and hawksbills are also captured. According to Marydele Donnelly, Sea Turtle Conservancy’s director of international policy. “Shrimp trawls kill more sea turtles than all other sources of mortality in U.S. waters combined,”

Nearly 30 years ago, with shrimpers facing the potential closure of the shrimp trawl fishery in U.S. waters because of sea turtle bycatch, fishing industry leaders joined forces with NOAA biologists to develop a device that would allow sea turtles to escape from the shrimp nets. The initial design was a modification of a device developed to exclude marine trash and cannonball jellyfish (the favorite food of leatherbacks), from their shrimp nets. The Turtle Exclusion Devices (TEDs) used today continue to evolve and, as you can see in the diagram above, the device is basically an inexpensive net insert consisting of metal bars surrounded by a frame. The shrimp trawl net itself is wide-mouthed at the entrance and tapers gradually towards the catch bag at the end of the net. The TED is positioned to allow shrimp or target fish species to pass through the bars and into the catch bag. When a turtle enters the net, the TED “gate” opens and redirects the turtle out of the net through a top or bottom exit hatch.

While TEDs are required by law for shrimp trawlers in the U.S. and Mexico, many fisheries around the world lack similar regulations. Despite their success in the shrimp fleet, TEDs are not yet legally required by the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) for thousands of other U.S. trawler fisheries that operate in the Atlantic and the Gulf of Mexico, targeting fish species such as black sea bass, tilefish, Atlantic bluefish and herring, mackerel, squid, butterfish, Mid-Atlantic sea scallops, blue and horseshoe crabs, cannonball jellyfish, monkfish, skates, and spiny dogfish. These commercial fisheries land millions of pounds of catch each year, and many operate in areas where sea turtle bycatch is likely, but they are not required to fit their nets with TEDs.

In 2019, the Trump administration accelerated its efforts to de-regulate the U.S. shrimp fishery. Consistent with their other attempts to overturn a wide range of environmental and Endangered Species protections, the administration amended the law requiring TEDs on all shrimp trawlers in the Gulf of Mexico and South Atlantic regions. The new ruling allows trawler vessels smaller than 40 feet to operate without using TEDs. Boats larger than 40 feet must have turtle excluders installed by April 2021. In January 2021, environmental organizations led by Earthjustice’s legal team notified U.S. Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross, NOAA Administrator Neil Jacobs, and NOAA Assistant Administrator for Fisheries Chris Oliver (all Trump administration appointees) that the U.S. would be in violation of the Endangered Species Act by amending the law. Environmentalists and turtle biologists remain hopeful that the Biden administration will be able to rescind the amendment and avoid a protracted lawsuit battle.

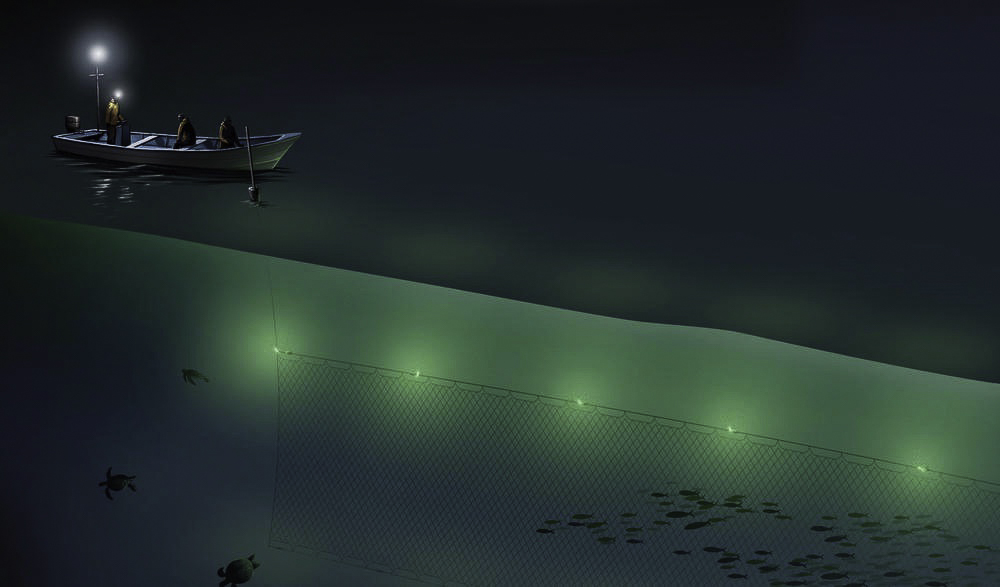

Photo Credit and Caption: Courtesy of the World Wildlife Fund , NOAA, Arizona State University, and artist Matt Twombly/WWF-US. To address fisheries bycatch-related sea turtle deaths, the World Wildlife Fund partnered with NOAA and scientist Jesse Senko of Arizona State University, to design the world’s first solar-powered LED fishing net.

Photo Credit: Courtesy of NOAA Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center. The sun sets as fishermen deploys nets with green LED lights attached.

Photo Credit: Courtesy of the NOAA-PIFSC. By attaching an LED light every 30 feet on the net’s float line, turtles are able to see the gillnets more easily.

Imagine, for a moment, a tennis net strung across the bottom of the ocean for several miles, and you begin to understand the long and deadly reach of a gillnet fishery. A gillnet is a wall of mesh netting suspended from regularly spaced floaters on the surface and is designed to trap target fish, not other marine animals, but the nets don’t discriminate. The size of the mesh openings correspond to the target fish species, with an opening that allows the fish to get its head through the netting but not its body. The fish’s gills get caught in the mesh as it tries to back out of the net. The sheer number of gillnet fishers underscores the problem: Off the coast of Indonesia, an estimated 300,000 small-scale vessels fish those waters. In Peru, an estimated 100,000 miles of gillnet are set annually along the coast. In North America, U.S. and Canadian gillnet fisheries have proliferated exponentially along both coasts.

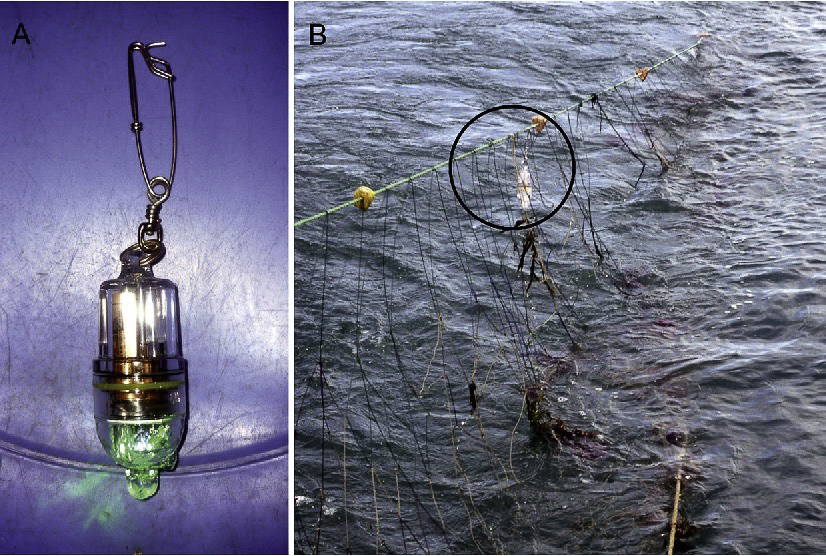

High rates of gillnet bycatch threaten not only sea turtles, but also whales, dolphins, sharks, rays and seabirds. Sea turtles rely on visual cues when foraging for food, and scientists are now turning to LED lights to illuminate gillnets as a promising bycatch reduction technology. Illuminating fishing nets appears to deter turtles and other species from approaching and becoming entangled, decreasing bycatch by 60% to 95%—without reducing the overall harvest of target fish species. In addition to sea turtles, illuminated gillnets can potentially reduce bycatch threats to other non-target marine animals. Studies in Mexico found green sea turtle bycatch reductions between 40% and 60%. Researchers in Indonesia showed that green, olive ridley and hawksbill sea turtle bycatch was reduced by 60% and the target catch increased. And in Peru, illuminated nets have reduced green sea turtle bycatch between 65% and 80%. Collaborators have also expanded research to areas in Pakistan, Ecuador, Italy, Slovenia and Ghana.

Photo Credits: WWF-Peru / Julia Maturrano.

Peru hosts five species of sea turtles that feed in its nutrient-rich waters, which have been identified as a globally significant high-risk zone for sea turtle bycatch. Peruvian fisheries are estimated to catch tens of thousands of turtles per year, mainly in their gillnet fishery, posing a significant threat to Eastern Pacific leatherbacks, South Pacific loggerheads and the critically endangered Eastern Pacific hawksbills. Small-scale fishing activity in Peru represents a major source of income for more than 500,000 people in coastal communities with few economic resources other than those related to fishing. Any changes to target species catch rates can affect their livelihoods.

A study by the University of Exeter and the Peruvian nonprofit ProDelphinus, showed that green LED lights mounted along the top of floating gillnets cut accidental bycatch of sea turtles by more than 70%, and that of small cetaceans (including dolphins and porpoises) by more than 66%. In Sechura Bay, 114 pairs of control and illuminated nets were deployed to estimate the costs of bycatch prevention measures. Understanding these cost challenges ($34 USD for a single turtle and $9200 for the entire gillnet fishery in the bay) illustrated the need for institutional support from national ministries, international non-governmental organizations and the broader fisheries industry to make possible widespread implementation of net illumination as a sea turtle bycatch reduction strategy.

Scientists also successfully tested a prototype in Baja California Sur, Mexico, where an average of six to eight turtles are accidentally caught per boat per day, which translates to thousands of turtles saved every year in that region alone. To address fisheries bycatch in the most remote areas, the World Wildlife Fund partnered with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and scientist Jesse Senko of Arizona State University, to design the world’s first solar-powered LED fishing net.

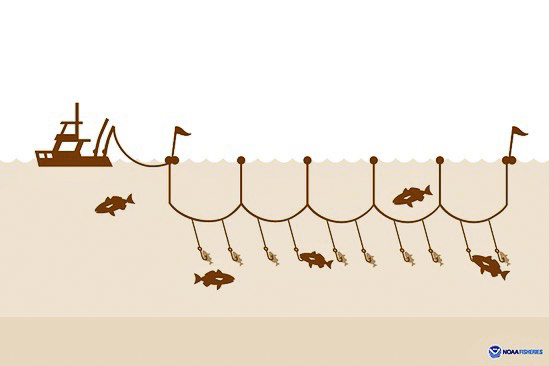

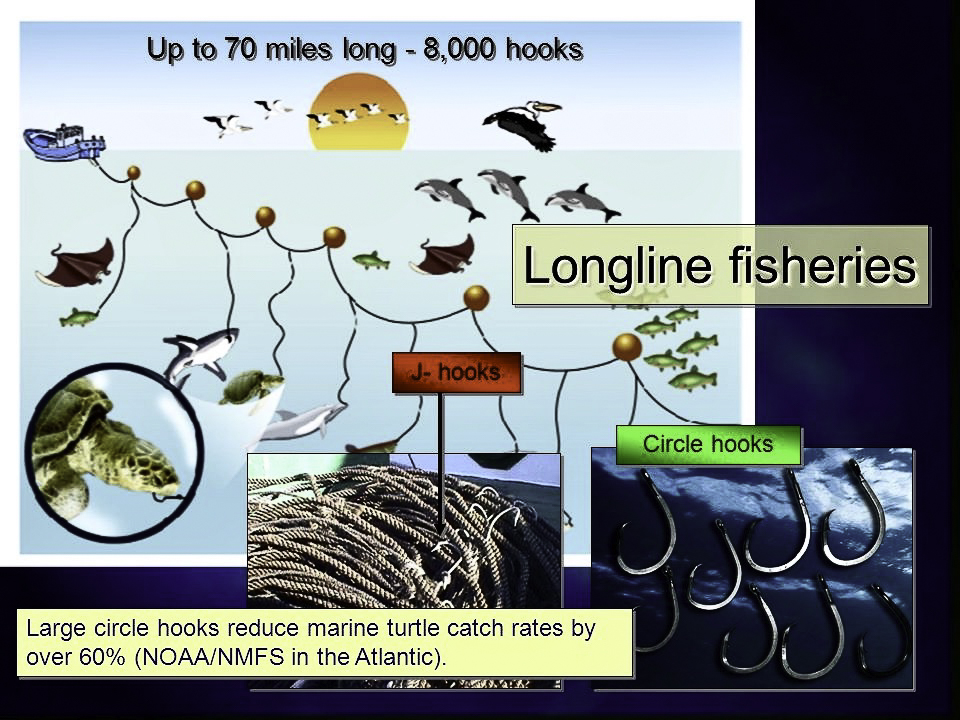

The longline fishery uses hooks rather than nets or other mesh entrapment devices. Drifting longlines are used in pelagic fisheries targeting tuna, swordfish and other billfish. The longline, or mainline, is suspended horizontally at a pre-determined depth in the water column by buoy lines attached to regularly spaced surface floats. Baited hooks are attached to the mainline by means of thinner branch lines, also called leaders, snoods or gangions. Hook type and size varies with different target species, but J-hooks and “circle” hooks are both used in longlining.

Once deployed, longline sets can soak for hours, and are typically baited with squid, mackerel, and sardines. The hooks fish at different depths, depending on their position and the curve of the mainline between floats. A radio beacon is attached to the mainline so that the vessel can keep track of it. A high-flyer buoy is used to monitor gear position while fishing, and lightsticks are often used to target certain fish species. Unfortunately, lightsticks attract sea turtles (mostly loggerheads and leatherbacks) to the baited hooks. The average U.S. longline set is 28 miles (45 km) long. There are limits on longline length in certain areas. Longline fisheries range from local small-scale operations to large-scale industrial fishing fleets.

The traditional use of J-hooks in longlining pose the greatest risk to sea turtles because they are large and can easily penetrate the turtle’s flippers, head, mouth, or neck. If a turtle swallows an entire hook, it can become lodged in the turtle’s digestive track, thereby hindering normal feeding and digestion, resulting in starvation and possibly death. Loggerheads are most often hooked in the mouth or esophagus, and leatherbacks are commonly hooked around the front flippers. Entanglements may also lead to severe lacerations and infections caused by constriction of the branch lines on the turtle’s soft parts. Turtles entangled or hooked at depth typically drown because they cannot reach the surface to breathe.

Current bycatch reduction measures for longline fisheries include the use of circle hooks, with the shape and smaller opening reducing the likelihood of turtles and marine mammals ingesting hooks or being caught. When hookings do occur, they are superficial and primarily in the mouth, which reduces internal injury and allows for safer release. Circle hooks used in combination with finfish bait like mackerel also significantly reduce sea turtle bycatch. The World Wildlife Fund collaborated with the Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission (IATTC) and other partners in introducing the circle hook in eastern Pacific longline fisheries. As a result, marine turtle deaths may be reduced by as much as 90 percent without adversely affecting catches of swordfish and tuna. Circle hooks are now required in Atlantic pelagic longline fisheries.

Proven solutions do exist to reduce bycatch threats to sea turtles, seabirds and other marine animals. Although the challenges are daunting, it is exciting to see how much research is currently underway to reduce mortality. The World Wildlife Fund is among many nonprofits working to develop, test, and implement alternative fishing gear and to integrate conservation science into effective fisheries management throughout the global ocean. Bycatch mortalities can often be reduced by modifying fishing gear so that fewer non-target species are caught or so that non-target species can escape. In many cases, as we saw with TEDs and circle hooks, these modifications are relatively simple and inexpensive. WWF, for example, created the International Smart Gear Competition to promote the development of innovative fisheries technology, offering more than $50,000 in prize money to attract new ideas that might provide valuable solutions to reducing bycatch mortality in the world’s troubles fisheries.

Yes, there is cause for hope!

The Marine Stewardship Council (MSC; logo shown above) is an international, science-based nonprofit dedicated to ending overfishing worldwide. For over 20 years, the MSC has been committed to protecting the last major food resource that is truly wild: seafood. Among several top priority projects is their commitment to reducing the incidental catch of sea turtles, dolphins, and other marine animals. MSC’s over-arching vision is one in which the world’s one shared ocean is teeming with life and seafood supplies are safeguarded for this and future generations. They work with fisheries, retailers, restaurants, and other companies to change the way that the ocean is fished, address and combat seafood fraud, and make it easier than ever for consumers to identify and purchase wild-caught seafood that is sustainable and traceable through the supply chain.

In recent years many governments have responded by funding basic research, requiring better data collection, and adopting time and area closures, gear restrictions, and onboard fishery observer programs. Conservation advocates, fishers, gear manufacturers, researchers, and other stakeholders have put forth similar efforts to quantify the extent of the problem, identify hot spots, forge solution-oriented partnerships, develop “cleaner” fishing techniques, certify and market sustainable seafood, and so on.

What can you do as a seafood consumer? Recent research reveals that concerns for our global ocean are driving a new wave of consumer activism. North American shoppers are increasingly ‘voting with their forks’ for sustainable seafood. The next time you shop for seafood look for the MSC fish logo on seafood in your grocery store fish counters, on packaged seafood, and on restaurant menus to ensure that the wild-caught seafood you buy was is certified as sustainable.

VIDEO: Reducing Bycatch Helps Restore Sea Turtle Populations (NOAA Fisheries)

https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/video/reducing-bycatch-helps-restore-sea-turtle-populations

click images to enlarge

To help build global awareness, we would appreciate it if you would share this post with your friends and colleagues. Please choose one of the options below which includes email and print! Thank you.

Sad and hopeful the same time!

Reading and learning about how our appetite for sea food and maybe the greed of some fishing companies, has created such disasterous outcome, makesme want to learn more and share the informations.