ePostcard #156: Raven-Walking

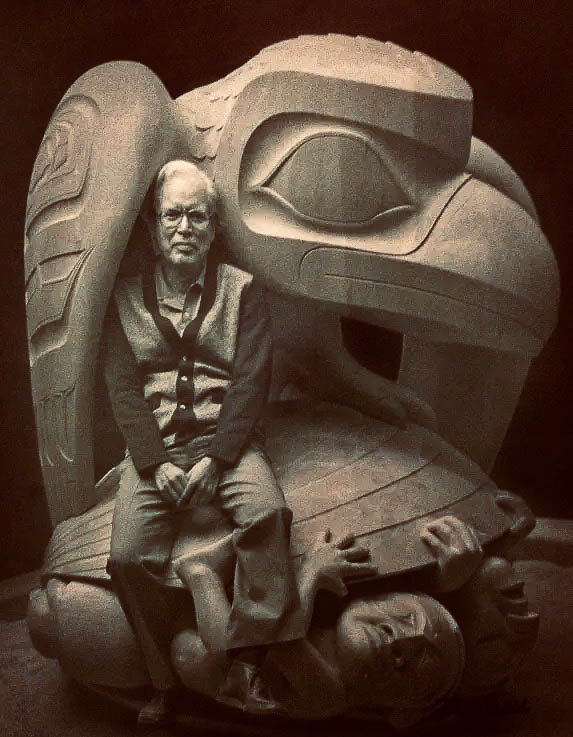

Photo Credits: Haida artist Bill Reid’s cedar sculpture, The Raven and the First Men, shows Raven releasing humans from a cockle shell. The image is courtesy of photographer Kimon Berlin (CC BY-SA 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0>, via Wikimedia Commons) and the Museum of Anthropology at the University of British Columbia. The image of Bill Reid below is also courtesy of the MOA at the University of British Columbia (BillReidMOA.jpg).

RAVEN-WALKING STORIES

The Haida have a rich oral history that has been passed down through the generations over thousands of years. The collection of “Raven-Walking” stories, or Xuuya Kaagang.ngas in the Skidegate dialect of the Haida language, tell of Raven traveling the Earth and changing it to make it fit for humans. The Haida name for Raven is Nang Kilslas, which means The-One-Whose-Voice-is-Obeyed. In the Haida view, Raven-Walking made the world the way it is – and created Haida Gwaii.

By the end of the 19th century, nine-tenths of the Haida had fallen victim to the impacts of exploitive colonization and European-introduced diseases, especially smallpox. By 1900, the ancient villages, some of the largest pre-agricultural settlements in history, were cemeteries of fallen house-poles and rotting cedar-plank lodges. The survivors of this tragedy lived in two clapboard missionary towns. John Swanton, a young Harvard-educated ethnographer employed by the Bureau of American Ethnology, arrived on Haida Gwaii in 1900 to study the culture of the islands and collect artifacts for the American Museum of Natural History.

Thankfully John Swanton met a young Haida, fluent in English, named Henry Moody, who would act as his translator and entrée into Haida society. Swanton quickly realized that transcribing Haida stories was the most important task he could set himself to while on the islands. Henry Moody introduced John Swanton to two Haida poets named Ghandl of the Qayahl Llaanas, baptized in English as Walter McGregor, and Skaay of the Qquuna Qiighawaay, called by the missionaries John Sky. Swanton spent more than a month with each of them, and collected long works from both. It quickly became clear to the ethnographer that the stories ought to be recorded exactly as they were told, in the original language, preserving the storyteller’s vocabulary and syntax.

Swanton believed that there was a single original version for each myth in a culture; and that a storyteller’s variations on a story were conscious artistic choices, not mere corruptions of the original. In this he differed from Franz Boas (a pioneer of modern anthropology credited with developing the linguistic and cultural components for recording indigenous stories and rituals) and his ethnographer colleagues, who preferred to make English prose reductions of the myths, trying to distill some elusive standard version of each story. Swanton’s Haida texts are thus some of the only unadulterated storytellers’ works to survive the eclipse of classical North American Indian culture.

The congruence of Haida oral histories with ongoing archeological, geological and paleoecological research efforts is truly remarkable. Skil Hiilans Allan Davidson, a Haida hereditary chief and archaeologist who took part in the excavations at three karst caves, emphasizes that artifacts and animal remains are more than just ancient discoveries. Whether it’s a bear mandible or a fossilized human footprint, archaeological and paleontological findings have meaning for Indigenous people. According to Davidson, Haida people have lived on and cared for Haida Gwaii for thousands of years. His nation’s oral histories recount Haida people’s deep history in this region, and archeologists are just now starting to catch up.

“Then Raven-Walking told only the black bear, marten and land otter to be on Haida Gwaii. And the strip of ocean between the mainland and [Haida Gwaii] was narrow. The tide flowed back and forth in this, and he pushed the islands apart with his feet […] at the time there was no tree to be seen.”

From John Swanton (1908) Haida Texts — Masset Dialect

This quote describes the ancient landscape of Haida Gwaii and to the presence of certain mammals on the islands. In the Haida Gwaii-Hecate Strait area, environmental change was rapid and substantial in early post-glacial time (Fedje and Josenhans, 2000; Lacourse and Mathewes, 2005). In fact, Rolf Mathewes’ use of the term ‘Lost World’ for Haida Gwaii is quite appropriate for an ancient landscape where climate, vegetation communities, distribution of animal species, and even the nature and configuration of the physical landscape was quite unlike that of today (Fedje and Mathewes, 2005; Koppel, 2005). At 15,000 years ago there was an 80-km-wide grassy plain (Hecate Plain per Fladmark, 1979) in the area of present-day Hecate Strait. By 10,700 years ago the plain was drowned and dense spruce-hemlock forests had risen to encompass all but the highest elevation areas of the archipelago.

Northwest coastal peoples were skilled mariners without equal in the indigenous world. Haida Gwaii is the most isolated archipelago on the west coast of the Americas, and more than three decades ago Knut Fladmark and Phil Hobler suggested that these islands might well provide the key to a more complete understanding of the earliest human occupation of the North Pacific coastline. The story continues …

Our next ePostcard will share the exciting scientific research efforts by Haida and non-native experts that are revealing the history of Haida Gwaii and the archeological evidence in support of at least 13,000 years of human presence on the archipelago. Stay tuned!

Reference Source: Quaternary Science Reviews

Volume 272, 15 November 2021, 107221(https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2021.107221)

Karst caves in Haida Gwaii: Archaeology and paleontology at the Pleistocene-Holocene transition

To help build global awareness, we would appreciate it if you would share this post with your friends and colleagues. Please choose one of the options below which includes email and print! Thank you.

Fascinating.

I remember seeing Reid’s sculpture while at the museum while marooned in Vancouver in the 2011 chaos. Creation stories, like those of the Navajo too, are insights into early mans dealings with the meaning of life. Now we search the heavens for particles of exploded Nova stars to understand were humans evolved.

Audrey, Thank you for another very interesting post card! When first looking at the colored photo of the wooden sculpture I immediately began wondering about its size. Of course, as soon as I clicked on to the additional information, the b & w photo with Bill Reid sitting on it gave me the answer:) It must be very impressive to view it in person. Even more compelling is the legend of Raven-Walking and the ethnographer’s attempt to preserve the Haida people’s language and heritage that you have described in your epostcard. I look forward to learning more.