ePostcard #65: Tern, Tern Tern!

Turn! Turn! Turn!

To every thing there is a season,

A time to be born, and a time to die.

A time to mourn, and a time to heal.

A time to break down, and a time to build up.

A time to weep, and a time to laugh,

A time to embrace, and a time to refrain from embracing.

A time to gain, and a time to lose.

A time to keep, and a time to cast away.

A time to keep silence, and a time to speak.

A time of love, and a time of hate.

A time of war, and a time of peace.

I swear it’s not too late, turn, turn, turn.

(Adapted courtesy of Pete Seeger and Ecclesiastes )

Special Note: Please forgive the play on words in my title for this ePostcard. I have also taken several liberties with the lyrics of Pete Seeger’s famous Viet Nam-era plea for world peace, the ballad “Turn! Turn! Turn!” The song’s lyrics were drawn directly from biblical text in Ecclesiastes and Seeger simply set those words to music, adding the phrase “I swear it’s not too late” as the final sentence and setting the world in motion with a chorus of the words “turn, turn, turn.” My version of the lyrics is meant to be non-denominational and all inclusive, illuminating the environmental and human challenges we are facing globally—with the world turning, turning, turning beneath our feet.

Antarctic terns are truly grace on the wing—feather-penned calligraphy on a blue sky canvas. In my mind’s eye, I imagine what their elegant flight trails would look like as they hunt for fish, each successful plunge-dive preceded by a hovering blur of wings. These beautiful terns (photo #1 and #7) are easily identified by their all-over gray plumage and blood red, dagger-shaped bill, short legs, and webbed feet. Unlike the Arctic terns, which are legendary for their great looping migratory marathons between their Arctic breeding grounds and their austral spring and summer “wintering” areas in the Southern Ocean and Antarctica, Antarctic terns have a circumpolar subantarctic distribution. Breeding populations (races) are found on the remote islands of Tristan da Cunha (northern limit), Gough Island, Iles Kerguelen, St. Paul and Amsterdam Island, South Georgia, South Sandwich Islands, South Orkney Islands, South Shetland Islands, New Zealand’s subantarctic islands, Macquarie Island and Heard Island and the Antarctic Peninsula.

Some Antarctic tern populations are migratory, while others are not, remaining near their breeding areas throughout the austral winter. Migratory Antarctic tern populations often seek out the edges of the pack ice, and may range north to the southern coastal areas of South America and South Africa. They are the only tern species that breeds on South Georgia (race Sterna vittata georgiae), with an estimated 2,500-5,000 breeding pairs, and most of those are essentially non-migratory and don’t stray far from their breeding areas during the austral winter. These terns are gregarious, often fishing in large flocks just beyond the surf zone. They feed on small fish and various crustacea, and will sometimes scavenge in the intertidal zone for stranded marine organisms.

Tern, tern, tern—to everything there is a season. Antarctic terns return to their breeding colonies on South Georgia in the austral spring (September and October). Most colonies are situated on a gravelly hilltop or a glacial outwash plain that provides an unobstructed view of approaching predators (skuas, petrels, kelp gulls). Described by ornithologists as “loosely colonial,” Antarctic terns prefer sites where their nests can be widely-spaced but still close enough for adults to cooperate in defending the colony. Social-distancing, tern style! These terns are nest minimalists, creating a shallow scrape on the ground that they line with a few pebbles. The female lays 2-3 mottled gray eggs between October and January. As you might imagine, the nests are difficult to spot because the eggs and chicks are so well camouflaged. Fledging of the chicks occurs between January and May, and the parents continue attending the chicks and feeding them intermittently for several weeks after fledging. Even with these defensive adaptations, predators still occasionally manage to take eggs or chicks from unattended nests in the colonies.

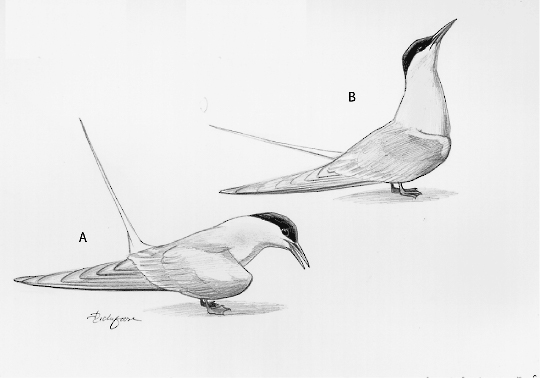

If you have ever observed a tern colony, you know that there is nothing “minimalist” about their courtship and pair-bonding displays—or their shrill kik-kik-kria alarm calls and bombardier responses to a predator or territorial intruder, including humans. I was fascinated to learn from Tim and Pauline Carr, the authors of Antarctic Oasis: Under the Spell of South Georgia, that they often observed Antarctic terns actively engaged in pair-bonding and other displays throughout the austral winter season. Having discovered a small tern colony on a ridge above Stromness Bay, I decided to position myself between the colony and the rocky shoreline, where I could watch but not disturb the terns as they traveled back and forth to the sea to fish. I’m always mesmerized just watching them fly and the surround-sound pleasure of their chit-chit-chit-chirr display calls. I was able to observe an aerial pair-bonding display, which involved the male carrying a small fish in its bill as the pair flew together over the water. I also saw terns apparently defending “contested airspace” over their feeding territories, engaging in a ritualized aggressive display, the so-called “upward flutter.” Following their flight paths with my binoculars, I observed both birds fluttering vertically upwards to great height, the lower bird with its neck twisted and its bill pointing up, the upper bird with its neck arched and its bill pointing down. During non-aerial, low-intensity defense of nesting or feeding territories, both sexes often assume a “bent” (or almost bowing) posture, in which the head and bill are pointed towards the ground, the wings are open and partially spread, and the tail is raised (refer to photo/illustration #2). In aggressive interactions, the bent-posturing male faces the antagonist or intruder and presents its black cap. In courtship, the male faces to one side, turns its black cap away from its mate. The corresponding appeasement display is referred to as the “erect posture.”

My use of the phrase “tern, tern, tern” was inspired by a strangely beautiful display (I assumed it to be a male) that I observed and photographed that day. I’d never seen it before and have not been able to find a description of anything like it in the scientific or birding literature. My photographs #’s 3-6 show segments of the male tern’s display but a video would have shown that it was turning around and around (photo’s #4 and 5) in that slanted posture. It was all alone on that boulder “stage” and flew off shortly thereafter to engage in a dramatic upward flutter display with another tern. It appeared to successfully defend its territorial airspace and flew back to land on the boulder. I would love to understand that twirling display!

Drawing Credit: Bent posture (A) and Erect posture (B). (Redrawn from Cullen 1956 by Julie Zickefoose for Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology’s “Birds of the World”)

To help build global awareness, we would appreciate it if you would share this post with your friends and colleagues. Please choose one of the options below which includes email and print! Thank you.

Wonderful observation and splendid writing.

I love the Turns, specially the Antarctic turns with their dramatic color patterns, Their graceful and elegant bodies. And you have captured their grace and strength so beautifully.

And your explanation of the turns courting dance and flights was so vivid that it felt like I was there.

Thank you thank you and THANK YOU!