ePostcard #165: Eavesdropping on the Brain: Whales, Dolphins and Porpoises

SLEEP PATTERNS IN WHALES, DOLPHINS AND PORPOISES

The Cetacea—whales, dolphins and porpoises—are obligate water dwellers and must make a conscious effort to surface and breathe. How do cetaceans manage to get any sleep in the water or while swimming? We know that cetaceans have several mechanisms that prevent water from flowing into their blowholes while they sleep, but this doesn’t answer the question. Humans are unconscious breathers, which means that we breathe automatically when we are awake or asleep (unless we suffer from sleep apnea). Whales and dolphins are conscious breathers, which means they have to actively decide when to breathe, which can be tricky for an animal that spends all of its time underwater.

When humans sleep, their entire brain (both hemispheres) is engaged in restorative sleep. Cetaceans, on the other hand, sleep by “resting” one hemisphere of their brain at a time, with the opposite hemisphere functioning normally for breathing and danger awareness. As we learned in ePostcard #163, this is called unihemispheric slow-wave sleep because only one brain hemisphere sleeps at a time. Interestingly, whales do not appear to have REM sleep (rapid eye movement), which is also characteristic of humans. Whales and dolphins periodically alternate which side is sleeping so they can get the required amount of rest. The amount of sleep and the way that cetaceans sleep, however, can vary greatly between species. Some cetaceans sleep with on eye open as well, changing to the other eye when the brain hemispheres change their activation during sleep.

When sleeping, whales typically stay in a horizontal or vertical position close to the surface of the water, often in groups. The muscles around the whale’s eye bend it into position so that they can focus on objects or potential threats above and below the water. Their eyes are also suited to see in low-light conditions underwater.

Resting or sleeping in the water requires certain behavioral adaptations to maintain adequate thermogenesis. Whales and dolphins can lose a great deal of body heat when not active or moving, so some species keep swimming even while they are sleeping. Humpback Whales have been found resting motionless on the surface of the water, but for only 30 minutes so they can start moving again to keep warm. Studies of dolphins, in the ocean and in captivity, show that they shut down half of their brain for short durations of time while they continue to swim and breathe. They will continue to switch the hemisphere that gets rest and can sleep for a couple of hours at a time, usually at night. The bottlenose dolphin was reported to sleep for approximately 33% of the day, where sperm whales are estimated to sleep for just 7% of the day!

Newborn whales and dolphins need a lot of sleep and motherly care. During their first month, calves don’t leave their mother’s side. They eat, sleep, and swim in the mother’s slipstream. In fact, if the mother stopped moving, the calf would sink and possibly drown. Adult whales keep afloat because of the thickness of their layer of blubber which is is a combination of fibrous and fatty connective tissues, and large oil-filled cells. The blubber layer isn’t just for insulation in cold waters; it also stores energy when the whale isn’t eating, and it helps keep the whale buoyant. The young calves’ are born with a layer of baby-fat, but it is not enough to keep them buoyant. For mom, this means non-stop swimming and alertness during the first weeks. Meanwhile, the newborn can enjoy the once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to have a long sleep and rest both brain-halves simultaneously.

NORTH PACIFIC GRAY WHALES

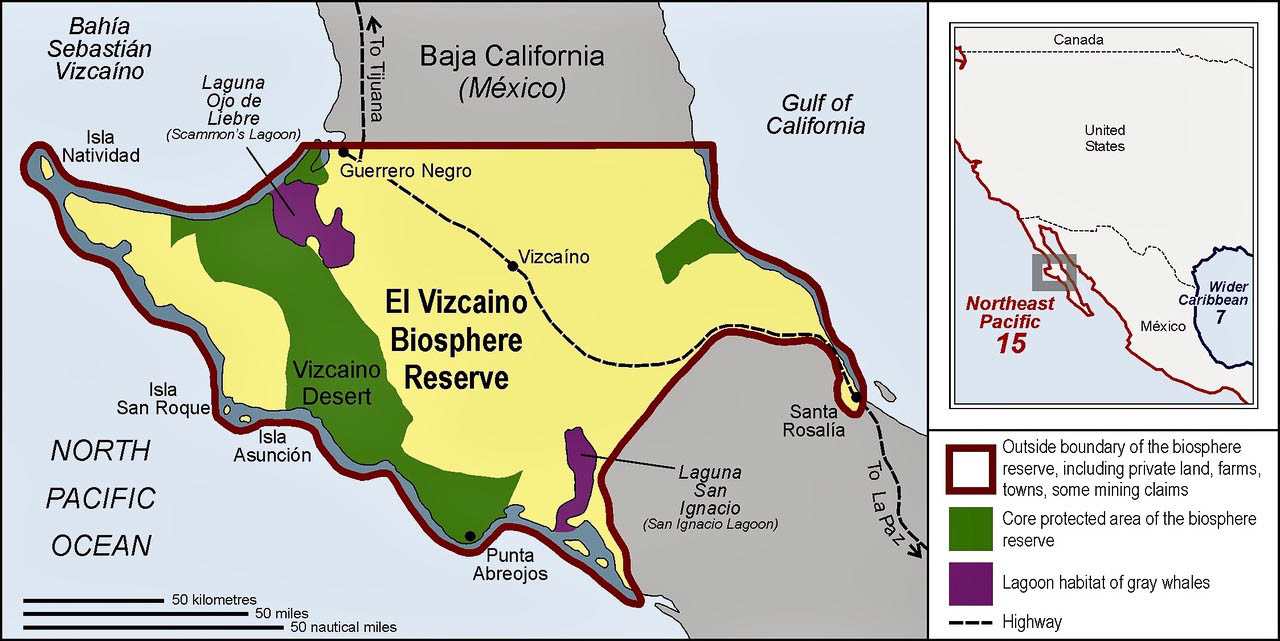

It was one of those lovely February days in western Baja’s Laguna San Ignacio, one of two huge coastal lagoons in the Whale Sanctuary of El Vizcaíno. Laguna San Ignacio and Laguna Ojo de Liebre (once known as Scammons Lagoon) are critically important reproduction and wintering waters for the North Pacific gray whale. The sanctuary is encompassed within the El Vizcaíno Biosphere Reserve, which is a World Heritage Site and the largest Biosphere Reserve in Latin America. Mexico’s protection of these winter breeding grounds has been paramount in the remarkable recovery of this species after near-extinction as a result of commercial whaling, which once focused on these very lagoons.

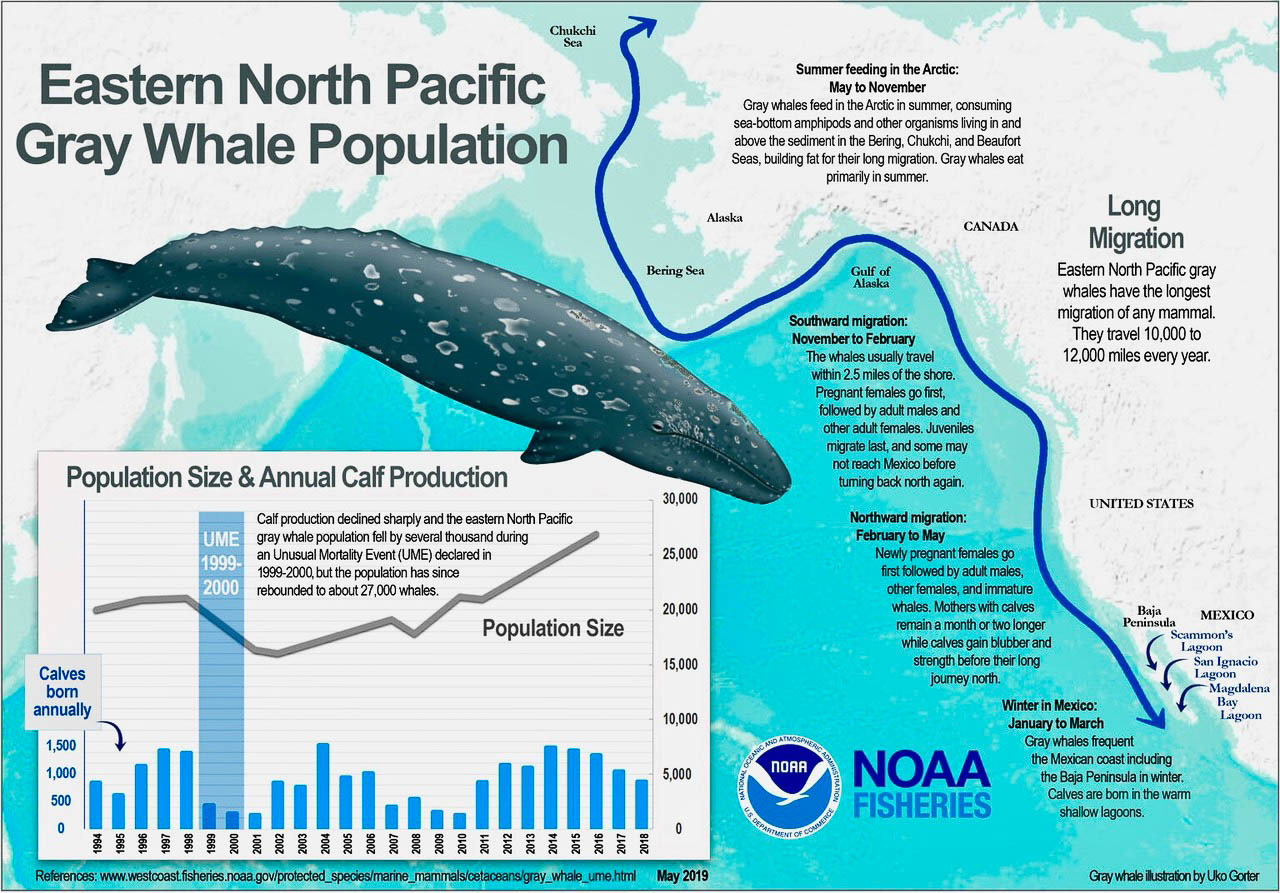

The majority of the gray whales that breed and overwinter in these lagoons will migrate north in the spring to their summer feeding grounds in the Chukchi, Beaufort and Northwestern Bering Seas. The female gray whales that arrived here in early December had given birth and now focused on getting their calf ready for their perilous migratory journey north to their summer feeding grounds.

The winds had settled into a gentle riff on the water and we were drifting in the panga, with the outboard motor silenced. Sitting in a panga surrounded by jade green water and watching gray whales is a prescription for happiness that knows no bounds. We could see whale spouts in the distance wherever we looked. The perfect decision on that afternoon was simply to sit and watch in silence, letting the whales come to us if they chose to do so—and they did.

To be fortunate enough to drift close one sleeping at the surface, seemingly undisturbed by our presence in the panga, was a brief immersion into a whale’s world that I never expected. This gray whale (below) seemed young, perhaps a few years short of breeding age, and it was floating just below the surface with its eyes shut and its twin blowholes exposed above the water. To be close enough to look into the eye of this whale once it woke and approached our panga, was truly one of life’s most moving experiences. It didn’t appear to perceive our presence as a threat. Given the commercial whaling that decimated gray whale populations here in the late 1800’s, I remain humbled in every way by these whales.

At birth, a gray whale calf is dark, its skin wrinkled and barnacle-free. In the warm calving lagoons in Baja California, the calf remains in close contact with its mother, often swimming onto her back or tail flukes. The calf will rest, eat and sleep while their mother swims, towing them along in her slipstream, which is referred to as echelon swimming. At times, the mother will sleep on the move because she cannot stop swimming for the first several weeks of a newborn’s life. If she does stop for any length of time the calf will begin to sink, this is because the calf is born without enough body fat or blubber to float easily. The blubber on an adult gray whale can be up to 10 inches thick. This might explain why mother whales in the nursery lagoons at San Ignacio are often observed with their calves semi-supported by their mother’s flipper as they come alongside the pangas. Before making the trip north, the baby grows and fattens on about 50 gallons of its mother’s milk a day. In the three photos below you can see three different gray whale mothers and their calves.

SLEEPING AND MIGRATION

Illustration Credit: Courtesy of NOAA Fisheries

Gray whales undertake one of the longest migrations of any animal on earth. They travel 12,000 miles round trip, from the icy waters of the Arctic to the warm lagoons of Mexico’s Baja California. Like other baleen whales, gray whales spend summers feeding in productive northern waters and then mostly fast during winter in their equatorial breeding grounds.

When underway, a migrating gray whale has a predictable breathing pattern, generally blowing 3-5 times in 15-30 second intervals before raising its fluke and submerging for 3-5 minutes. A gray whale can stay submerged up to 15 minutes, and travel at 3-6 miles per hour.

Mothers are very protective of their calves, and earned the name “Devilfish” from early whalers in the lagoons because of their violent defensive behaviors. Killer whales are a leading cause of gray whale deaths, especially juveniles, and many gray whales have orca teeth scars on their flukes. Bigg’s killer whales (also known as transients) are the primary predator of gray whales, and killer whale attacks on gray whale calves are common along the US west coast.

To help build global awareness, we would appreciate it if you would share this post with your friends and colleagues. Please choose one of the options below which includes email and print! Thank you.

I’ve got some catching up to do on your postcards! They all are so wonderful. But this is so fascinating and it touches my heart. I am in love with these gray whales – thank you for educating those of us who have never seen them but love them anyway. Someday I hope…

Learning how they sleep only generates more wonder and awe for me.

I worry about the fossil fuel export and plans to drill in the Arctic. I hope we can stop each and every one of these destructive things that endangers gray whales and the rest of the wildlife in the Arctic -including those who make the long migration. Thanks for your wonder-generating articles and gorgeous photography, as always.

Sadie, I thank you, as always, for your very kind words! I wanted you to know that I haven’t forgotten sending you books. I’ve been working through a major snarl with Sasquatch Books/Random House and they are currently reprinting the Salish Sea: Jewel of the Pacific Northwest. It should be back in print late this spring. Spread the word!

Audrey,

As I work here in my corporate office, I thoroughly enjoyed taking a break to read your wonderful Postcard about the whales and their sleeping patterns today! I learned so much that I never knew about! I thank you for enlightening me, as you always do! I so look forward to future excursions and continuing our own migratory journeys alongside you and the Cloud Ridge pods!

Thank you for making this day so special! – Lynn Cooper

Wonderful comments like yours are what keep me inspired and exploring the world around me! Thank you!

Thank you Audrey. I really enjoyed learning more about the whales, especially the mothering of the babies. Please keep writing to us. Ruth Salter