ePostcard #118: Nightwatch: Hatchlings Away (Part 4)

Cover Photo (above) Credit and Caption: Having finally reached the wet, surf-hardened sand, this hatchling is in fast-forward mode on its final sprint to the sea. (Photo courtesy of Courtesy of Boca de Tomates Turtle Camp and Red Tortuguera A.C.)

ePostcard #118: Nightwatch: Hatchlings Away (Part 4)

click images to enlarge

#2. Photo Credit and Caption: Courtesy of Travel + Leisure India and the Velas Turtle Festival organizers.

Caption: The lefthand photo shows female olive ridleys arriving and departing their nesting beach as part of the mass nesting event known as an arribada. On the right you see freshly emerged olive ridley hatchlings heading towards the sea. Females reach sexual maturity at about 15 years of age and nesting activity occurs in many coastal locations around India. The beaches at Odisha are famous for hosting one of the largest arribada aggregations in the world. During an arribada, thousands of females may nest over the course of a few days to a few weeks. Arribadas occur in Mexico, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Panama, Australia, India and parts of Africa. The largest ones occur in Costa Rica, Mexico, and India. Nicaragua has a significant beach in La Flor Wildlife Refuge. Other solitary nesting areas include Guatemala, Brazil, Myanmar, Malaysia, and Pakistan. Worldwide, olive ridleys nest in approximately 40 countries.

A student volunteer in India, a member of the Students Sea Turtle Conservation Network (SSTNC), carefully disentangles an olive ridley hatchling from a discarded fishing net on Rushikulya Beach near the village of Podampetta. It’s estimated that commercial fisheries in the Indian Ocean contribute to the deaths of thousands of sea turtles each year, most of which become entangled in discarded fishing gear or trapped in longlines, gill nets and shrimp trawls. Throughout the world, even in countries where sea turtles are protected under laws, they continue to be killed and traded on the global market for their meat and eggs, oil for traditional medicines, as a source of exotic leather (leatherbacks), and for their beautiful shells (hawksbills).

Photo Credits for #6 and #7: Courtesy of Kate O’Hara, Conservation Coordinator at the Loggerhead MarineLife Center.

Photo Credit #8: Courtesy of Elise Peterson.

Caption: The mass emergence behavior of turtle hatchlings—a “boil” of leatherbacks in these photos—is an effective strategy (called “predation dilution) that appears to improve hatchling survival rates in areas with higher densities of predators.

#9. Photo Credit and Caption: Courtesy of Magdalena Paluchowska.

Photo Credits for #’s 10-12: Photos courtesy of Dawn and Blair Witherington.

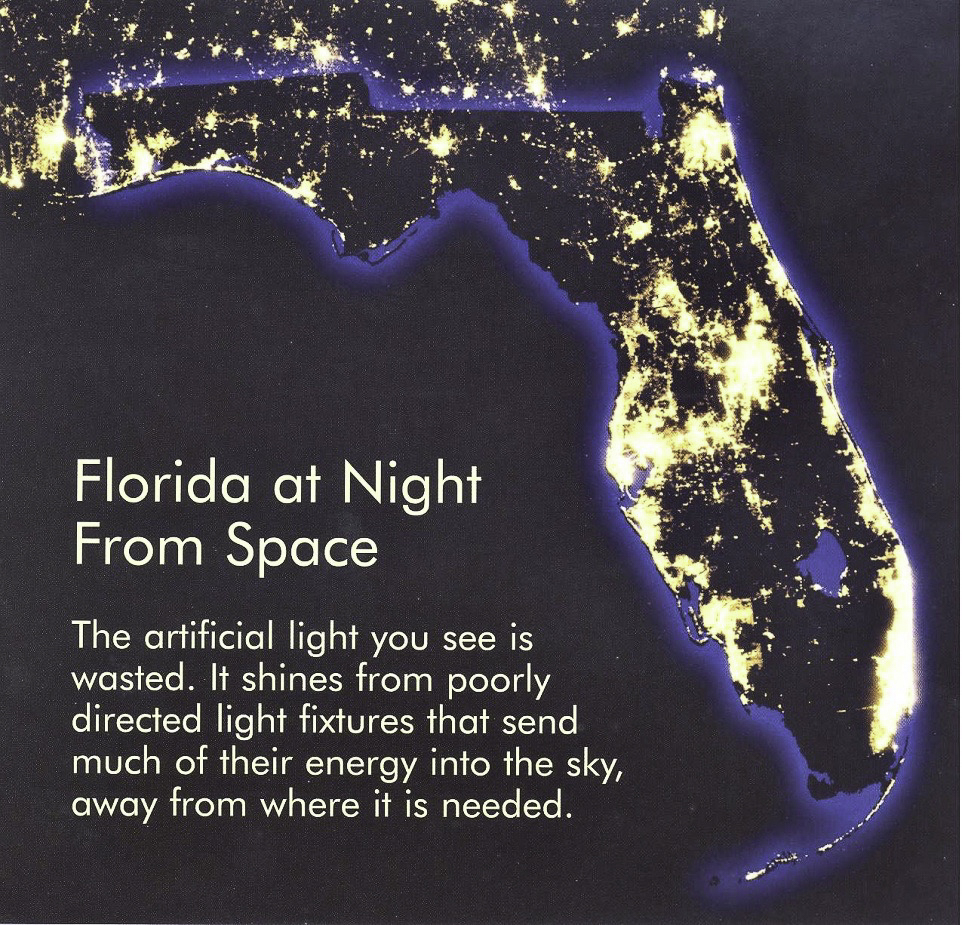

Artificial lights cause problems for hatchlings as they emerge from their nests and instinctively crawl toward the brightest direction, which would be towards the ocean on a naturally dark beach. Bright artificial lights attract and disorient hatchlings, causing them to crawl inland and away from the ocean or to wander aimlessly on the beach, all the while burning up vital stored energy that is crucial for survival if they do ever manage to reach the sea. Disoriented hatchlings often die from dehydration, exhaustion, terrestrial predation and as roadkill. If they do manage to eventually make it to the ocean, disoriented hatchlings have a lower chance of survival due to energy loss, which makes it harder for them to reach important off-shore habitats for feeding and increases their susceptibility to marine predators.

click images to enlarge

To help build global awareness, we would appreciate it if you would share this post with your friends and colleagues. Please choose one of the options below which includes email and print! Thank you.

Great postcard, never had thought about the impact of lights on turtles. it surely affects other species as well.

Carol, thank you! Light pollution is a huge problem throughout the world. Paul Bogard has written a fine book, called “The End of Night:Searching for Natural Darkness in an Age of Artificial Light” (2013), that speaks to this situation for humans and other animals. The ePostcard I did that inspired the turtle series was the one that concerned the role of artificial light in disrupting bird migration. I will return to the subject of light pollution in future ePostcards looking at impacts on humans, moths, bats, etc.

Thank you Audrey once again for such wealth of knoweldge and amazing images you gather and share with us. I am blown away especially by photo #9 and its explanation.

Thank you for this wonderful article, bringing together sea turtle research from around the world. It brought back memories of my turtle surveys in the village of Ostional in 1973 (article in National Geographic by Paul Zahl). Well done.