ePostcard #114: Nightwatch

ePostcard #114: Nightwatch

“Managing darkness has to be an integral part of future conservation planning and illumination concepts.” Dark Sky Association

The natural world is a busy place at night! As our human viewshed darkens, the mysterious sounds and vocalizations that enliven the nighttime world trigger our primal sensory awareness. The mountains that glowed so beautifully at sunset become sharp-edged silhouettes at twilight. Attuned to the scents that guide their nocturnal travels, scavengers, predators, prey, and pollinators are on the move. It is not surprising that our sense of vulnerability heightens in unfamiliar landscapes at night. Our human lives are daylight-focused, but countless animal species are dependent on darkness, with more than 60% of invertebrates and 30% of vertebrates classified as nocturnal (night-active) or crepuscular (twilight-active). Almost all small rodents and carnivores, 80% of marsupials, and 20% of primates are nocturnal.

With the exception of ocean bottom, subterranean or cave-dwelling creatures, the extraordinary diversity of life on Earth evolved in a 24-hour cycle of daylight and darkness—a circadian rhythm—that repeats with each planetary rotation. Even photosynthesis, the process by which chlorophyll-rich, green plants and microscopic phytoplankton synthesize the “building blocks” that form the base of the food chain, is powered by sunlight. The circadian “clock” also drives the daily and seasonally-dynamic timing of the biological processes and behaviors that sustain life on our planet, which includes everything from cyanobacteria, fungi, plants, invertebrate and vertebrate animals, and humans. These remarkable adaptations, which have evolved over hundreds of millions of years in response to the Earth’s circadian rhythms, are entrained in the DNA of plant and animal species up and down the evolutionary tree. For most animal species, the changing length of the photoperiod (daylight) is the most predictive environmental cue for the seasonal physiological and behavioral changes that are critical for survival, such as the timing of reproduction, migration, hibernation, and torpor.

Light pollution is defined as the excessive and inappropriate use of artificial light. Though it may not be as obviously toxic as a chemical spill, light pollution is now viewed by many biologists, medical professionals and conservationists as one of the fastest growing and most pervasive forms of environmental pollution. There is now little doubt that the relentless global spread of artificial light is impacting the health and well-being of humans, birds, mammals, reptiles, amphibians, and countless species of insects and other invertebrates. We are already seeing a decline in the number of nocturnal and light sensitive species in ecosystems that are in close proximity to urban centers. The four components of light pollution often combine and overlap, and include:

- Urban Sky Glow—the brightening of the night sky (usually bright orange, yellow, or pink) over inhabited areas as a by-product of artificial light being scattered by water droplets or particles in the air.

- Light Trespass—unwanted artificial light, such as that from a floodlight or streetlight, falling where it is not intended or wanted and illuminating areas that would otherwise be dark.

- Glare—excessive brightness which causes visual discomfort and can actually decrease visibility. Ill-designed lighting washes out the darkness and can radically alter the light wavelengths to which many forms of life, including humans, have adapted.

- Clutter & Over-illumination —bright, confusing, and excessive groupings of lights are typical of over-lit urban areas, where the use of artificial light exceeds what is required for a specific activity, including keeping lights on all night in an empty office building or on a cruise ship.

Each year, billions of night-flying migratory birds are forced to find their way through increasingly light-polluted skies. Light is a powerful stimulus for many animals. Some species, such as birds and moths, are compelled to move towards a source of light (a positive phototaxis response), while other species move away from it (a negative phototaxis response). In birds and moths, the positive phototaxis response to artificial light is often referred to as a “fatal light attraction.”

Birds use both visual cues and an internal magnetic compass for navigation and orientation, relying on wavelengths from the blue-green part of the light spectrum for direction. Laboratory studies have shown that birds are only disoriented under specific wavelength conditions and that a shift to greenish tinted outdoor lighting greatly reduces disorientation and associated mortality. About 200 bird species fly their migratory routes at night over North America, with the majority of fatalities occurring during spring and fall migration, when brightly lit buildings, communication towers, and other urban structures lure migrants into an urban maze of light pollution. Each year in New York City alone, about 10,000 migratory birds are injured or killed crashing into skyscrapers and high-rise buildings, according to records kept by the New York City Audubon Society. Nationwide, nearly 600 million birds die every year in collisions with buildings, according to the Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service estimates that as many as 50 million birds die each year from collisions with communication towers.

Saving migratory birds during the week-long Tribute in Light at the National 9/11 Memorial every September is a success story that has caught the attention of conservationists around the world. The twin beams of light that define the dramatic tribute rise more than four miles into the night sky in honor of the nearly 3,000 lives lost in America’s most devastating terrorist attacks. But these same columns of light that so elegantly trace the former outlines of the twin towers also lure thousands of migrating birds to fly through the city’s skyscraper canyons, where many die from exhaustion and from collisions with buildings and windows. Early visitors to the Tribute in Light reported seeing dense flocks of birds circling, swooping and diving in and out of the beams, not unlike the frenzied clouds of insects drawn to a porch light at night. In this case, however, the twin beams are powered by 88 xenon bulbs, each pumping more than 7,000 watts of bright light into the night sky in columns that can be seen from 60 miles away—or from space.

With thousands of migrants found dead each September on Manhattan streets and sidewalks, New York City Audubon’s Susan Elbin and other ornithologists started working in 2002 with city officials and the producers of the Tribute in Light to forge a conservation solution that would be successful for birds and people. It was not until 2005 that a fruitful partnership arose, with the tribute’s production team agreeing to turn off lights as needed. In 2007, NYC Audubon proposed the official protocol: If one or more birds crashes to the ground, dead; if the birds appear to be trapped (flying low in the beams and calling); or, if 1,000 birds are in the beams for more than a 20-minute period; then the lights are shut off for 20 minutes, to allow them to fly on. To better understand the deadly lure of powerful ground-based light sources on migratory birds and to develop strategies that might mitigate the hazards they pose, Cornell Lab researchers Andrew Farnsworth and Kyle Horton, pioneers in the emerging field of radar aeroecology, analyzed radar data from 143 Nexrad weather stations in order to track millions of migrating birds as they navigate the night skies across the continental United States. Looking specifically at the September radar data for Lower Manhattan, they found that the Tribute in Light attracted birds in densities up to 150 times their normal migration levels. The researcher’s reported that during one 7-night tribute event in 2010 at least 1.1 million migrants had been adversely affected by the illuminated memorial.

Susan Elbin, Farnsworth, Horton and other Cornell Lab-affiliated researchers gathered data and observations from the Tribute in Light events from 2008 to 2016, and after analysis, published their findings in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in 2017. The action plan that they set in motion for monitoring migratory activity during the annual event required that the researchers and an enthusiastic team of volunteers spend the night counting the numbers of migratory birds attracted to the twin beams of light using binoculars, radar and the naked eye. Every 20 minutes, team leaders take a photograph of the sky above them and count the number of birds they see in the beams of light. When the number of migrants approaches 1,000, the tribute’s lights are switched off for 20 minutes to give the birds enough time and darkness to resume their natural migrations. According to radar studies by Audubon’s Susan Elbin and other researchers, the 20-minute darkness intervals stopped the migrant’s abnormal behaviors within minutes—including circling at decreased speeds and lower altitudes, increased vocalization and aggregation at the lights. “These migrants only have enough energy to get where they need to go; the fatter you are the more energy it takes to fly, so it’s a fine balance,” said Elbin, “Light lures them in, and glass finishes them off. ”

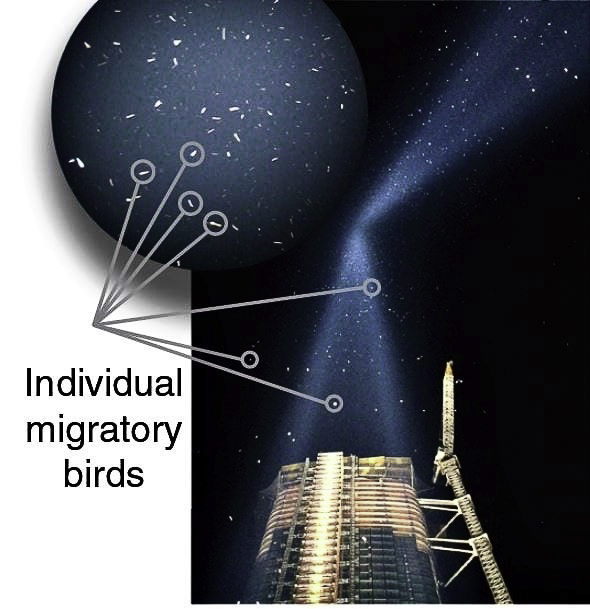

Photos, Credits and Captions:

#1. Photo Credit for the photo above: Courtesy of the New York Times (Gary Hershorn/Getty Images).

Caption: Birds and moths twinkle as they fly through the beams of lights as part of the Sept. 11 anniversary. Susan Elbin, an ornithologist and the director of conservation and science at New York City Audubon, finds herself awed by the vigil. “It’s very solemn,” she said. “The beams just sort of appear in the darkness and go on forever”— four miles up — “and when the sun rises the next morning it just disappears.” Unfortunately for the birds, the disorienting effect of the twin light beams has been found to cause exhaustion, injury and death. Many of the migrants fly straight from the light beams into nearby glass buildings.

click images to enlarge

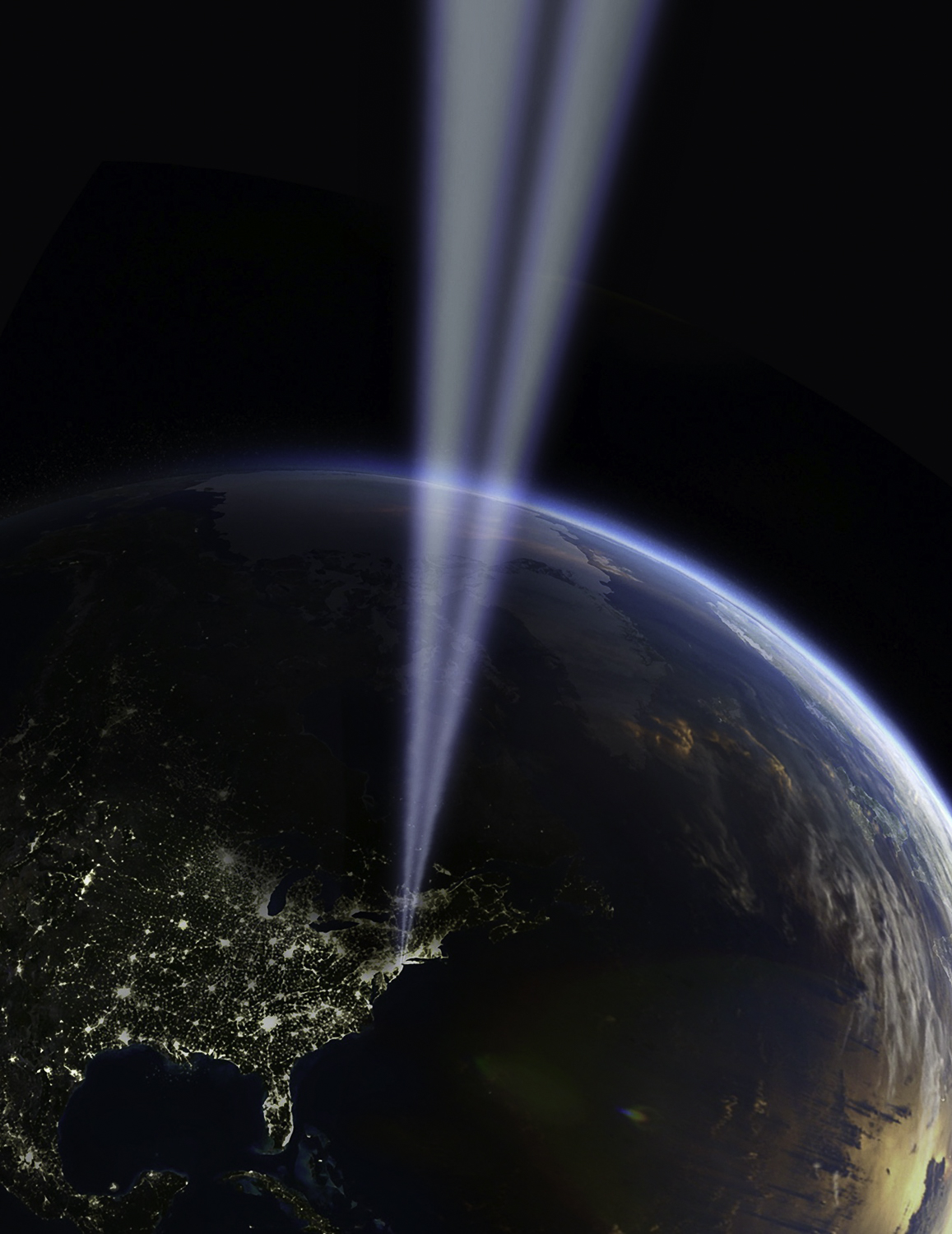

#2. Photo Credit: Courtesy of NASA Earth Observatory.

Caption: This view from space shows the twin beams that create the Tribute in Light at the 9/11 Memorial for an anniversary week each year.

#3. Photo Credit: Courtesy of Nazimayal Design Blog (2011).

Caption: This stunning image illustrates the two symbolic light towers that are integral to the Tribute in Light

#4. Photo Credit: Courtesy of the New York Times (Andrew Kelly/Reuters).

Caption: Members of the New York City Audubon Society monitor birds that are attracted to the Tribute in Light installation. Memorial organizers work with volunteers and ornithologists to keep an eye on bird activity while the lights are on. Once more than 1,000 birds are spotted in the twin beams, they shut down the installation for 20 minutes while the birds disperse.

#5. Graphic Credit: Courtesy of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Caption: Birds congregate in the beams of the 9/11 tribute lights in New York in 2015. New York is also one of several North American cities, including Chicago, San Francisco, and Toronto, with a “lights-out” policy, dimming illumination during migrating seasons in towers like the Chrysler Building and Rockefeller Center.

click images to enlarge

To help build global awareness, we would appreciate it if you would share this post with your friends and colleagues. Please choose one of the options below which includes email and print! Thank you.

Beautifully written coverage of this important topic. Thank you.

Thank you so much! I’m currently working on a light pollution-related sea turtle Nightwatch piece and one on moths before I finish the series on human health issues caused by light pollution. In the Cloud Ridge camping years, I offered several 4-day seminars that focused on nocturnally-active species (bats, flammulated owls, moths etc) and always built in night activities on our desert, ocean, river, tundra, and forest general ecosystem trips. No headlamps (unless we were in difficult terrain) and limited talking. Every sunset dinner I served ended in full darkness because few people allow themselves that luxury.

Thank you, Audrey! This is fascinating! I didn’t know about that Tribute in Light week and its devastating effect on migrating birds. One of my most wonderful experiences at night with no lights was in the Amazon in Peru, in a dugout canoe on a narrow river, seeing the Southern Cross in the sky for the first time and red crocodile eyes on the banks! I look forward to your sea turtle Nightwatch piece! Tortuguero in Costa Rica is where I saw a sea turtle lay her many eggs, all silent and in the dark, on my stomach in the Sand. Preserving the dark is necessary to all creatures on this earth!

I had no understanding of how many birds are lost to the lit-up sky and equally amazed at one solution by NYC AudubonSociety. Beautifully written as always!