ePostcard #123: On Thin Ice!

ON THIN ICE!

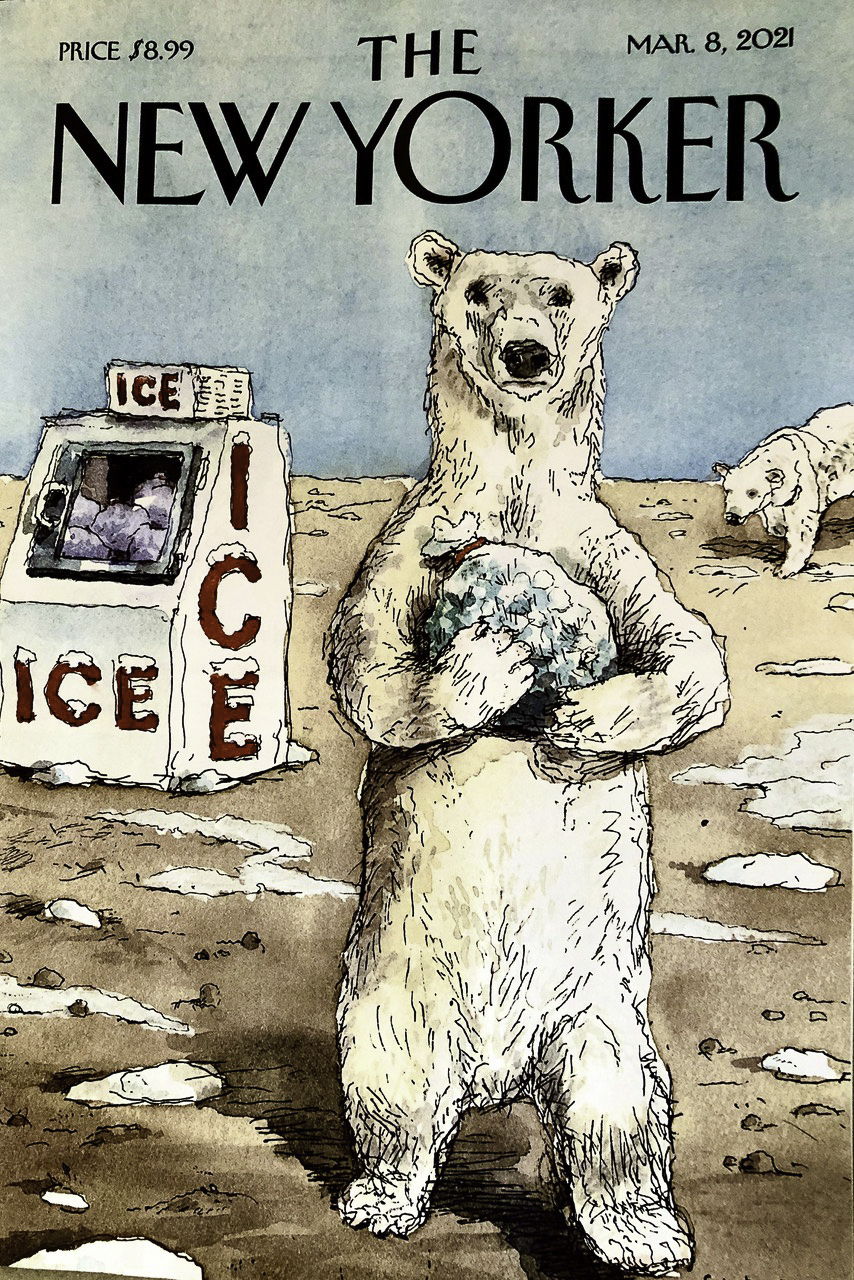

When I need to recover my bearings as a science writer, I often circle back to my fascination with polar regions. Sea ice has been very much on my mind lately, and especially the prospect of an ice-free Arctic in the not so distant future. The extent and thickness of Arctic sea ice has declined rapidly over the last several decades, an irreversible trend with far-reaching consequences for global climate and one that poses significant challenges to Arctic ecosystems, including the loss of habitat for Arctic animals such as polar bears and increases in coastal erosion that may directly impact Arctic people. A recent cover of The New Yorker magazine caught my attention with the portrayal of a polar bear, perhaps the most iconic symbol of the climate crisis, lugging home a bag of ice from a vending machine. The cover, purposefully cartoonish, speaks directly and poignantly to the plight of sea ice-adapted polar bears in a changing Arctic. The New Yorker often spotlights—with a single powerful cover image—the current events or issues that shape our world. Science writers often rely on stunning photographs to inspire environmental activism, but this cover got me back to my desk and ready to get to work. (See my Note to Readers at the end of this ePostcard.)

Cover Art: John Cuneo (Courtesy of The New Yorker)

What is sea ice and why is it important?

Sea ice forms, grows, and melts in the ocean. In contrast, icebergs, glaciers, and ice shelves float in the ocean but originate on land. For most of the year, sea ice is typically covered with snow. The Arctic Ocean is a semi-enclosed marine system, almost completely surrounded by land. As a result, Arctic sea ice is not as mobile as that in the Antarctic. Although sea ice moves around the Arctic basin, it tends to stay in cold Arctic waters. Arctic ice floes are more prone to converge, or bump into each other, and pile up into thick ridges. These converging floes make Arctic ice thicker. The presence of ridge ice and its longer life cycle leads to ice that stays frozen longer during the summer melt. Some Arctic sea ice remains through the summer and continues to grow the following autumn.

Arctic sea ice keeps the polar regions cool and helps moderate global climate. Sea ice has a bright surface; 80 percent of the sunlight that strikes it is reflected back into space. As sea ice melts in the summer, it exposes the dark ocean surface. Instead of reflecting 80 percent of the sunlight, the ocean absorbs 90 percent of the sunlight. The oceans heat up, and Arctic temperatures rise further. A small temperature increase at the poles leads to still greater warming over time, making the poles the most sensitive regions to climate change on Earth. According to scientific measurements, both the thickness and extent of summer sea ice in the Arctic have shown a dramatic decline over the past thirty years. This is consistent with observations of a warming Arctic. The loss of sea ice also has the potential to accelerate global warming trends and to change climate patterns.

Sea ice formation in the Antarctic contrasts sharply with that in the Arctic because Antarctica is a continental land mass surrounded by an ocean. The open ocean allows the forming sea ice to move more freely, resulting in higher drift speeds. However, Antarctic sea ice forms ridges much less often than sea ice in the Arctic. Also, because there is no land boundary to the north, the sea ice is free to float northward into warmer waters where it eventually melts. As a result, almost all of the sea ice that forms during the Antarctic winter melts during the summer.

Video Credit: Courtesy of NASA.

2018 Arctic Sea Ice Ties for Sixth Lowest Minimum Extent on NASA Record

https://youtu.be/pyIdwDbtcGs

Photo Credit: USGS image collection.

Why is Arctic sea ice important to polar bears and ringed seals?

Polar bears are formidable predators and powerful swimmers, and are perfectly adapted to the harsh demands of the Arctic environment. They prefer multiyear sea ice for protective cover and for a platform from which to hunt their favorite food, ringed seals. During the summer months, polar bears eat very little while they wait for the ocean to freeze. In areas such as eastern Baffin Island and Hudson Bay, where most or all of the pack ice melts by mid- to late summer, the entire bear population must come ashore for two to four months in summer and early fall to wait for the ice to freeze again.

Global warming is weakening the edges of the sea ice and shortening the season during which it is close enough to shore for polar bears to move easily between floes and onshore denning areas. Many bears find themselves stranded either on land, where fat-rich prey is hard to find, or on ice miles out to sea. Although polar bears are considered capable swimmers, they have not often been observed swimming far from land. A study in Polar Biology concluded that poor sea ice cover in the Arctic may contribute to increased polar bear mortality by forcing them to swim excessive distances between land and the pack ice edge. Since the start of the continuous satellite record in 1979, Arctic sea ice has declined in all seasons, particularly in summer. However, sea ice hasn’t declined the same way in all places, and polar bear populations have experienced different fates in different parts of the Arctic.

Photo Credit: Courtesy of Churchill Wildlife Guide/Natural Habitat Tours

Ringed seals, which are the most abundant seals in the Arctic, rely on stable sea ice to survive. The sea ice is where they rest, molt and reproduce. The most recent NOAA Arctic Report Card revealed that, due to persistent warming, the Arctic has now lost 95% of its sturdier ‘old ice’ (ice that is at least 5 years old). Consequently, only 1% of the Arctic ice pack is old ice, and the remaining ice is younger, and weaker. With perennial sea ice shrinking, some ringed seals have been observed adapting as best they can by seeking out land, and using rocks and mudflats as places to rest. Nevertheless, they still need stable ice because this is primarily where they give birth to their pups and raise them.

Ringed seals need stable sea ice but also plenty of snow. Sufficient snow accumulation sets the stage for the formation of deep snow drifts, which is where the seals dig their lairs. These little snow caves provide insulation and protection from predators, keeping the pups safe from polar bears, as well as killer whales, walruses, wolves, wolverines, sharks and even seagulls. The adult seals also claw ‘breathing holes’ into the bases of their lairs in order to gain access to the water below, which allows them safer access for hunting their own food. When snow cover is insufficient, unweaned pups are exposed to predation. Indeed, studies have revealed a link between decreased snow depth and seal pup mortality.

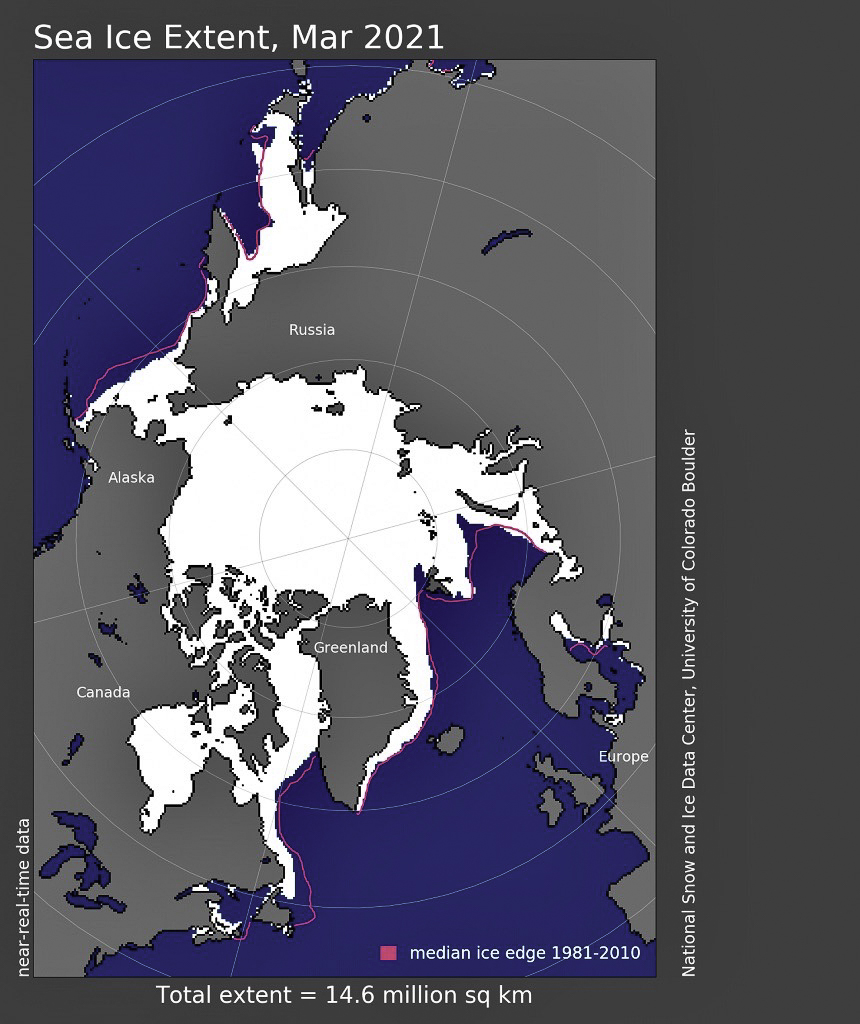

March 2021 Sea Ice Map Credit: National Snow and Ice Data Center.

The seasonal maximum extent of Arctic sea ice has passed, and with the passing of the vernal equinox, the sun has risen at the north pole. While there are plenty of cold days ahead, the long polar night is over. Arctic sea ice extent averaged for March 2021 was 5.65 million square miles. This was 135,000 square miles above the record minimum set in 2017 and 305,000 square miles below the 1981 to 2010 average. The average extent ranks ninth lowest in the satellite record, which began in 1979. The magenta line shows the 1981 to 2010 average extent for that month.

A Note to Readers: First, I’d like to extend my thanks for your expressions of concern and best wishes for my recovery! My apologies for being absent from my desk for the past couple months. I’ve been slowly working through some unfortunate side effects resulting from a MAKO total knee replacement on March 10, a surgery necessitated by injuries I suffered in a fall on an icy night in mid-February. Any illusions I had about aging gracefully have been humbly set aside as I have struggled to recover functional range of motion. Between ongoing physical therapies and pain medication, I’ve not had the mental energy or concentration to write my weekly Cloud Ridge ePostcards.

To help build global awareness, we would appreciate it if you would share this post with your friends and colleagues. Please choose one of the options below which includes email and print! Thank you.

Hi Audrey! I’m so glad you are feeling well enough to send these ePostcards again. Although I’m a chemistry major as you know, I am taking a geoscience senior seminar this semester called The Cryosphere — and we just a unit on sea ice, so I particularly enjoyed reading this postcard! Lots of love.

Dear Audrey,

I was happy to see your e-postcard today and to hear that you are making progress recovering from your fall.

Love, Ruth

Wow ! This was interesting- especially the difference between the two regions’ ice, the reflection of ice in relationship to the temperature of the ocean, and the loss of “old ice” in the Arctic. I loved the illustrations: cartoon, maps, and pictures, but most of all I am glad to hear that you are feeling better.