ePostcard #124: The Plastic Tsunami

Photo Credit: Courtesy of Florida Sea Grant.

THE PLASTIC TSUNAMI

Sea turtles have spent the past 100 million years roaming seas free of plastics. Today, the global impacts of plastic pollution on marine biodiversity are among the greatest environmental challenges of the Anthropocene. Over 600 marine species, including sea turtles, seabirds, seals, sea lions, whales, fish and countless invertebrates have experienced the toxic legacy of our throwaway society. Sea turtles, our most imperiled ocean sentinels, are especially vulnerable because both adults and juveniles are lured into consuming floating plastic bags that resemble jellyfish and algae-coated plastic fragments that look and smell like food—deadly attractions for hungry turtles.

Photo Credit: Courtesy of Chris Jordan. Seabirds that depend on food from the sea, like this Laysan albatross on Midway Atoll in the North Pacific, often mistake plastic for food with deadly consequences. It is estimated that 99% of seabirds will have ingested plastic by 2050

Plastic, one of the most useful materials ever invented, ranks among the most pervasive and persistent pollutants on Earth. Each year, more than 10 million tons of plastic waste ends up in the ocean—that’s a rate of almost 15 tons every minute. Today, millions of tons of plastic trash are found in all five ocean basins, and from the Arctic to the Antarctic. How does all this trash get into the sea?The majority of ocean-based plastic originates with commercial fisheries, aquaculture, and maritime activities and the rest comes from land-based sources such as beach litter, urban and storm runoff, construction, inadequate waste disposal and management, and illegal dumping. Of the 400 million tons of plastic products manufactured worldwide each year, nearly half are classed as single-use. It’s estimated that more than 1 trillion plastic bags are discarded worldwide each year. The environmental toll of single-use plastics — bags, straws, cups, packaging, utensils — is difficult to grasp because the vast majority of these products are not recyclable and end up in landfills, incinerators or as litter.

It is increasingly common to see wave-deposited accumulations of non-biodegradable plastic flotsam on remote beaches around the world. Even when recycling is an option for our discarded plastics, if you assess the environmental impacts of recycling a plastic container, for instance — the collection, sorting, chemical processing and associated emissions, and eventual end of life treatment — it doesn’t often pay off ecologically. The high costs of these steps, the low commercial value of recycled plastic, and the low cost of readily available virgin material mean that plastic recycling is rarely profitable and requires considerable government subsidies. Scientists estimate that only 9% of the 9 billion tons of plastic the world has produced since the 1950’s has been recycled. The remaining plastic has been buried or ended up in open dumps for burning, in oceans and other waterways, and scattered across human and natural landscapes worldwide. At current rates of consumption and recycling, there will be around 12 billion tons of plastic waste to contend with by 2050.

UNDERSTANDING THE ROLE OF OCEAN GYRES

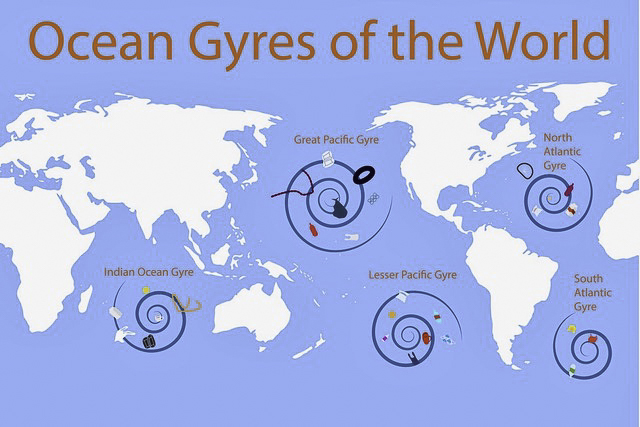

The story of what happens to plastic products that end up in our oceans, either by accident or by intention, will take us on a wild ride along the large systems of rotating ocean currents called gyres. There are five major subdivisions of the world ocean recognized by oceanographers: the Pacific Ocean, Atlantic Ocean, Indian Ocean, Southern Ocean, and Arctic Ocean. Wind, tides, and differences in temperature and salinity drive ocean currents. The ocean churns up different types of currents, such as eddies, whirlpools, or deep ocean currents. Larger, sustained currents—the Gulf Stream, for example—go by proper names. These larger and more permanent currents make up the systems of currents known as gyres. There are five major gyres: the North and South Pacific Subtropical Gyres, the North and South Atlantic Subtropical Gyres, and the Indian Ocean Subtropical Gyre. Currents don’t just move water. They move people and goods, as well as plastic pollution and debris. In each of these five gyres there are major concentration zones (garbage patches) of floating plastics in a variety of sizes.

To get a perspective on the magnitude of our plastic crisis, I want to take you on a voyage to the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. This patch is undeniably the most notorious, and spans waters from the West Coast of North America to Japan, and is bounded by the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre. The GPGP is actually comprised of the Western Garbage Patch, located near Japan, and the Eastern Garbage Patch, located between the U.S. states of Hawaii and California. In most cases when people talk about the “Great Pacific Garbage Patch,” they are referring to the Eastern Garbage Patch (EGP). This constantly rotating ocean current is situated in an atmospheric area known as the North Pacific Subtropical High. These two rotating collections of marine garbage (the WGP and EGP) are linked together by the North Pacific Subtropical Convergence Zone, which is located a few hundred miles north of Hawaii. This convergence zone is where warm water from the South Pacific meets up with cooler water from the Arctic. The zone acts like a highway that moves debris from one patch to another across the vast expanse of the Pacific Ocean.

Map Credit: Science in the News (SITN); Harvard University (Graduate School of Arts and Sciences). This simplified map shows the five major gyres, which are large systems of rotating ocean currents that drive global ocean circulation.

Map Credit: Courtesy of the NOAA Marine Debris Program. This map is an oversimplification of the major ocean currents and areas of marine debris accumulation (including “garbage patches”) in the Pacific Ocean. There are numerous factors that affect the location, size, and strength of all of these features throughout the year, including seasonality and El Niño/La Niña phenomena.

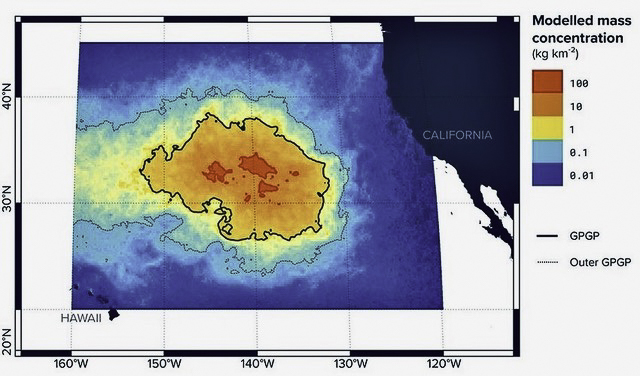

Photo Credit: Courtesy of Laurent Lebreton, the nonprofit Ocean Cleanup Foundation and an international team of scientists.

The North Pacific Subtropical Gyre, a slowly moving, clockwise spiral of currents created by a high-pressure system of air currents, is essentially an oceanic desert, filled with tiny plankton (phytoplankton and zooplankton) but few big fish or marine mammals. This giant circulating ocean current is home to far more than plankton, however, and is estimated to contain 1.8 trillion plastic items weighing well over 80,000 tons. Covering an expanse of ocean three-times the size of France, the Great Pacific Garbage Patch lies between Hawaii and California. Researchers have recently identified “microplastic hotspots” in places where deep-ocean currents serve as “conveyor belts” in transporting microplastics and depositing them on the seafloor in large sediment-rich accumulations. These hotspots are essentially the deep-sea counterparts of “garbage patches” that collect on the ocean surface and spinoff to wind up on the world’s beaches.

Imagine, for a moment, being a gyre “hitchhiker” aboard a floating raft of plastic trash in the midst of the Eastern Pacific Garbage Patch. Watch how the current collects its load of trash. The area in the center of a gyre tends to be very calm and stable. You can see how the circular rotation of the gyre draws debris into this stable center, where it becomes trapped. For example, a plastic water bottle discarded off the coast of California, for instance, takes the California Current south toward Mexico. There, it may catch the North Equatorial Current, which crosses the vast Pacific. Near the coast of Japan, the bottle may travel north on the powerful Kuroshiro Current. Finally, the bottle travels westward on the North Pacific Current. The gently rolling vortices of the Eastern and Western Garbage Patches gradually draw in the bottle.

Once these plastics enter the giant vortex of the patch, they generally degrade into smaller microplastics under the effects of sun, waves and marine life. As more and more plastics are discarded and find their way to the gyre, the concentrations of both macro- and microplastics in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch will continue to increase.

Map Diagram Credit: The Ocean Cleanup and the Ocean Voyages Institute.

This diagram of illustrates the concentration zones of marine trash in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. Much of the floating plastic consists of fragments and tiny bits called microplastic. In that sense, the garbage patch is really more like a garbage soup. Though soupy, the collection of plastic can be a deadly trap for the marine creatures who encounter it. The debris found in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch patch comes primarily from the Pacific coasts of North and South America and Asian areas along the Pacific Rim. According to a recent article in the journal Nature, “Evidence that the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is rapidly accumulating plastic,” the patch is actually not a solid mass of plastic but is made up of an estimated 1.8 trillion small pieces weighing over 88,000 tons. That figure puts the amount of GPGP plastics possibly 16 times greater than previously thought. As much as 75 percent of the debris was larger than five centimeters and at least half of the GPGP plastics collected in the study were from marine-based sources. The preponderance of marine-sourced plastics in the patch, which included strong nets, traps, ropes and floats used by fisheries and other marine industries, is attributed to their purposely-engineered durability in the marine environment.

Plastics are completely foreign to life, so animals have been unable to mount any evolutionary defense against them. Our final ePostcard in this series, Deadly Attraction, will explore what scientists are discovering about why sea turtles and other marine animals consume plastic and what happens when they do. Stay tuned!

To help build global awareness, we would appreciate it if you would share this post with your friends and colleagues. Please choose one of the options below which includes email and print! Thank you.

Thank you for the work you do, for your gorgeous photography, and for trying to educate us about plastic and these garbage gyres. It is truly heartbreaking to see these picures – these creatures don’t deserve this kind of death from our throwaway society worldwide.

Thank you for your comments! The last ePostcard in this series will focus on why marine animals–from plankton to whales–eat plastic.

It’s heartbreaking… but people need to know about these garbage gyres so we can collectively do better. I will spread the word. Thank you for all that you do to make the world a better and more beautiful place through your eyes and lens, as well as your writings.

Hi Audrey; tried to share this on facebook and they said cloudridge.org is spam! Any other way to share your ePostcards there? Thanks.

We are trying to solve this problem, which originates with Facebook and not with Constant Contact. Obviously, we are not spam and are being targeted for our conservation messaging. For now, I would encourage you to forward any of our ePostcards that resonate with you and your family to friends and colleagues who might be interested.

Audrey,

As it was mentioned by Captain B, it is so heart breaking.

The explanations of the gyres, the visuals are so effective to understand how this plastic trash soup happens and how it travels…so frightening and sad what we have done to our beautiful and fascinating world and not to forget our precious resources.

On a personal level so many of us are trying to live without using plastics which is a huge challenge, but what can be done with the existing amounts?!

Trying to spread the words, will share the link via emails.

Thank you for your work educating and reminding us.