ePostcard #155: A Voyage to Haida Gwaii

Note of Acknowledgment: Cloud Ridge’s May 2022 voyage to Haida Gwaii—the traditional, ancestral, and unceded territory of the Haida people—enriched our understanding of the uniqueness of Haida Gwaii and the Haida culture. Visitors to the archipelago are asked to sign the Haida Gwaii Pledge and honor the “Haida Ways of Being.” We extend our deep gratitude to the Haida Nation for their hospitality and support during our visit. I’ve attached the key elements of this pledge at the end of this ePostcard as a reminder that we are all stewards of our homeland—wherever that might be.

HAIDA GWAII

Travel with Cloud Ridge to a remote island world—the beautiful and storm-battered archipelago of Haida Gwaii (formerly the Queen Charlotte Islands)—the ancestral home of the Haida people (pronounced “Hydah”). “Haida Gwaii” means “Islands of the People” in the Haida language. In 2010, in accordance with the historic Haida Gwaii Reconciliation Act, the entire archipelago was renamed as part of the Kunst’aa guu – Kunst’aayah Reconciliation Protocol between the provincial government of British Columbia and the Haida people.

Rising dramatically along the Pacific Northwest edge of the North American continental shelf, this mountainous archipelago is located more than 80 nautical miles west of the British Columbian mainland encompasses more than 150 islands and islets. The archipelago is separated from the mainland to the east by the notoriously rough waters of Hecate Strait, Queen Charlotte Sound to the southeast, and Vancouver Island further to the south. To the north, Dixon Entrance separates Haida Gwaii from the Alexander Archipelago in the U.S. state of Alaska.

Gwaii Haanas National Park Reserve is located in the southernmost part of the Haida Gwaii archipelago. The only way to travel to Haida Gwaii is by boat or by air, and the sense of isolation is palpable. It is a wild place like no other. Our voyage was made possible by BC-based Bluewater Adventures’ Island Solitude, a 12-passenger motorsailer, her stellar crew, and my Pacific Flyway: Waterbird Migration from the Arctic to Tierra del Fuego (2020) co-author and trip leader, Dr. Rob Butler.

In preparing for the trip, I read Elizabeth May’s Paradise Won, which recounts the struggle by the Haida and non-native activists alike to create Gwaii Haanas National Park Reserve. In my early years of guiding in Alaska, my first introduction to the Queen Charlottes (as they were known then) was flying over them and looking down on ravaged, clearcut patches of forest. I felt an overwhelming sadness. I would soon become aware of similar environmental struggles going on in Alaska’s Tongass National Forest, which is located in the state’s southeastern panhandle and on islands in the Alexander Archipelago. The Tongass is the largest US national forest and was the focus of bitter disputes over logging in the 1990s. Canada and the United States share a dismal history when it comes to indigenous cultural survival and the devastating environmental impacts imposed on tribal homelands throughout North America.

Elizabeth May’s book reminds us that those who love their land and want to hold it in trust for future generations will always be stronger than those who are only intent on extraction and exploitation, all in the name of economic development and the old lie that flies in the face of realities on the ground. The book was originally published 32 years ago, in 1990, and the Forward to the 2020 Edition of the book begins with a quote from Dr. Wade Davis, which I include here because it so eloquently expresses the extraordinary and historic achievements of the Haida.

A New Dream of the Earth

“Forty years ago in a remote archipelago known then as the Queen Charlotte Islands, multinational timber companies dominated the economy, dictated public policy, and determined the very mood and civic culture of a place visited by few. Today these companies are gone, more than half of the land is protected, and what timber production remains is in the hands of the Haida, who are today in control of their destiny in a manner that would have been unimaginable when I lived on the islands in the 1970s. Haida Gwaii has emerged as one of the iconic travel destinations in the world. What was achieved in a single generation only happened because those who loved that land—Haida and non-Haida alike—took to the barricades and called for a new geography of hope, a new dream of the earth.”

—Wade Davis (reflection on the significance of the creation of Gwaii Haanas National Park reserve), January 2020

B.C. Leadership Chair in Cultures and Ecosystems at Risk

Professor of Anthropology University of British Columbia

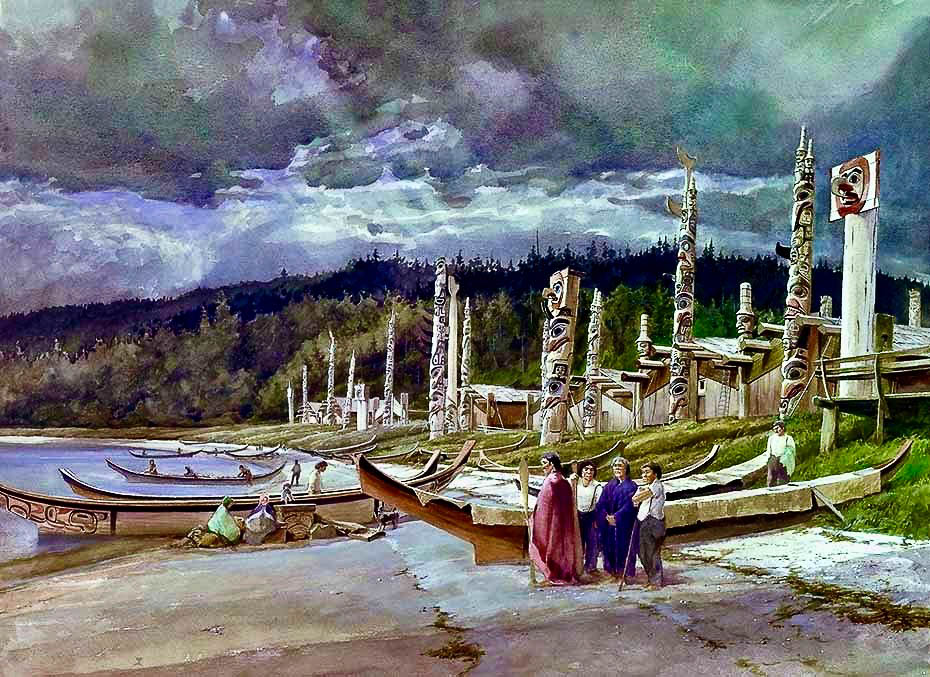

Painting Credit: “Skidegate — circa 1878, southwest end,” original watercolor 22″ x 29” by Gordon Miller © 1986. Miller’s painting gives you a sense of what a Haida village would have looked like at the time of European contact. The painting is based on two archival photographs (Dawson, 1878) and (Dossetter, 1881) curated at the Canadian Museum of History.

“To the Haida, their world was the edge of a knife cutting between the depths of the sea, which to them symbolized the underworld, and the forested mountainsides, which marked the transition to the upper world. Perhaps because of their precarious position, they embellished the narrow human zone of their villages with a profusion of boldly carved monuments and brightly painted emblems signifying their identity. Throughout their villages these representations of the creatures of the upper and lower worlds presented a balanced statement of the forces of their universe. Animals and birds represented the upper world of the forest and the heavens, while sea mammals, particularly killer whales, and fishes symbolized the underworld. The transition between realms was bridged by frogs, beavers, and otters. Hybrid mythological creatures, such as sea grizzlies and sea wolves, symbolized a merging of several cosmic zones.”

Quote Credit: Dr. George F. MacDonald, from Haida Monumental Art: Villages of the Queen Charlotte Islands (University of British Columbia Press, 1983, 1994; University of Washington Press, 1995). The quote above is by Dr. George F. MacDonald, the renowned Canadian ethnologist and archeologist, and is excerpted from his remarkable book, Haida Monumental Art: Villages of the Queen Charlotte Islands. MacDonald’s book, an ethnographic monument in itself, is graced by hundreds of archival quality images by the earliest photographers to visit the Haida villages.

Skidegate was a large Haida village with over thirty houses. The village was first visited by fur traders in 1787 and for three decades was an important center of sea otter trade. A short period of whaling and a brief gold rush in 1850 increased the village’s wealth and led to a flurry of building and totem pole raising. In 1853 five hundred villagers canoed to Victoria on the first of twenty-five annual trading expeditions. These families returned with European diseases; only the survivors of other towns abandoned in the 1860s kept Skidegate alive. By 1883 the last totem poles had been raised and European-style structures began to replace the traditional Haida houses.

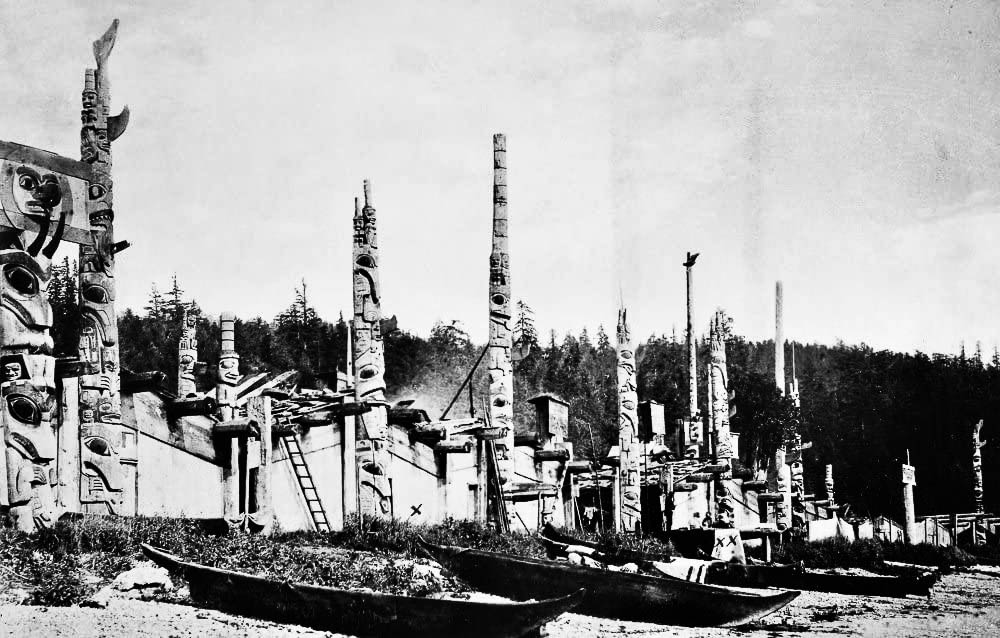

ARCHIVAL IMAGES

Photo Credit (above): Archival photograph by Charles F. Newcombe and taken in the Haida village of Tanu, located on the island of the same name. Courtesy of Newcombe and the British Columbia Provincial Museum (BCPM). Note that the eagle is situated at the top of the Eagle House pole and that the central roof beams are carved to resemble sea lion heads. The entry pole for Eagle House was sent by Newcombe to the British Museum and the sea lion central beams were sent to the British Columbia Provincial Museum in Victoria. In fact, many of the house totems were removed from the villages ravaged by small pox and abandoned and transported to museums in Europe and North America for preservation.

The contemporary Windy Bay pole (a portion is shown below) was carved and erected to honor the protesters who locked arms and blockaded the Lyell Island logging operations. The carved figures below recognize the “watchmen” locking arms. The lower image shows a contemporary Haida community house at Windy Bay.

IMAGES OF HAIDA GWAII &

GWAII HAANAS NATIONAL PARK RESERVE

Bluewater Adventures’ graceful MS Island Solitude at anchor (above) as we head out to explore.

The three images above portray sections of contemporary Haida poles carved from cedar on the grounds of the Haida Heritage Center at Skidegate. The Haida divided themselves into two groups (the anthropological term for this is “moiety”) called the Ravens and the Eagles. The moieties functioned primarily in the regulation of marriage, and all marriage partners had to be chosen from the opposite moiety. Descent was reckoned through the female line, so that the house chief might be an Eagle, while his wife and their children would be Ravens.

FROM THE FORESTS TO THE SEA

MY PERSONAL FAVORITES—ANCIENT MURRELETS

Illustration Credits: The symbolic artwork by Iljuuwaas Tyson Brown of an ancient murrelet (above) and the salmon being eaten by a killer whale (below) are courtesy of the Haida Gwaii Pledge document that visitors are asked to sign when they come to Haida Gwaii.

HAIDA GWAII PLEDGE FOR VISITORS

The Haida Nation is the rightful heir to Haida Gwaii. Haida citizens carry the inherent right to govern and steward our homeland. All people in Haida Territories hold a responsibility to protect this place for future generations. In return for your respectful actions, we will welcome you as guests to experience our Air, Ocean, Land and People.

Haida language is represented in the order of Xaayda Kil (Skidegate Haida) • Xaad Kíl (Old Massett Haida)

XaaydaGa Xaaynang.ngaay, yaahgudang dang ad Xaayda Gwaay guu hll k’awkaa

Xaads Xíináangaa: Xaayda Gwáay díi .ahl stúujuus dluu díi an yahgúudángáasaang

I will respect Haida Gwaii and Haida Ways of Being during my visit

I will honour these Haida Ways of Being by…

Yahguudang

Yahgudáng

Respect for all beings

Ad kyaanang

.Ahl kyáanáng tláagang

Ask permission first

Tll yahda

Tll yahda

Making it right

“Being mindful of my environmental footprint and my impacts on the earth, air and water.”

Gina ‘waadluxan gud ad kwaagid

Ginn ‘wáadluwaan gud .ahl kwáagíidang

“Everything depends on everything else. “

To help build global awareness, we would appreciate it if you would share this post with your friends and colleagues. Please choose one of the options below which includes email and print! Thank you.

Wow! What a way to begin my Sunday morning. Thank you for the inspiration as I set out on my morning walk.

Thank you for your kind words! This ePostcard (#155) celebrates the end of a much-needed sabbatical from writing that allowed me to restore my spirit and mental energy for the ongoing environmental challenges we face. These are difficult times to navigate for all of us who care about the world around us. Sometimes we simply need time to think and grieve for what we have lost. As a science writer, I also needed time to explore new approaches to inspiring and educating the next generation of conservation activists.

Joining you on the voyage to Haida Gwaii was an incredible experience. It is a pleasure to revisit the place in this ePostcard and to dive deeper into key points.

The scenic beauty of Haida Gwaii and rare moments with wildlife were somewhat expected components of the voyage. To my surprise and delight, we had many cultural experiences that gave new meaning to the place, to Haida Gwaii and to the world. Here are people who are reclaiming, restoring their connection to the Earth, to their sacred places. They are a new addition to my inspirations!

Thank you, Audrey, for the visit to this place, to the introduction to this culture, both in person and in this writing! Háw’aa!

Bravo!

It’s wonderful to be greeted by morning postcards again!

And though I may have seen the very same eagle, or anemone, or sunset, I always see it more clearly, more vividly, more completely through your photos. Thanks for both viewings!

Thank you Audrey for shedding light with your gorgeous photography and comprehensive account of another part of the native world. It is wonderful to learn that with their effort and naturalists like you getting the words out, hopefully the Haida people can preserve their heritage.

Thank you Audrey! I have missed your epostcards and was very happy to get this one, a wonderful trip. Ruth

Audrey, after having the privilege to hear your account of visiting this special place and its people, it was a treat open my email to the return of your ePostcards and this wonderful account of Haida Gwaii and the Haida people accompanied by your stunning photographs! Jim and I are especially glad you included the pledge; imagine if visitors were asked to sign and honor such a pledge in all of our sacred natural places, Thank you for once again opening our eyes and hearts to a land and culture about which we were previously unaware.

Dear Audrey, Sunday’s “epostcard” is the first of your series that I have had the pleasure of reading and viewing. Before reading your post I had only the vaguest idea of that area. In May, when Clyde was making plans to go there with you, and intrigued by the name “Haida Gwaii”, I had located the area on the map, but still did not have a sense of the place. Now, after looking at your wonderful photos and reading all of the information about the people who lived and still live there I am deeply impressed by their culture, creativity and their struggles. Your photos of the totems show what is there now and the contrast, as depicted in the watercolor painting by Gordon Miller of what it must have looked like about 1878, is striking. Thank you so much for all of the interesting, enriching information!

Melissa, thank you very much for your interest and your kind words. As you might imagine, describing the experience in the usual “sound bites” that seem to be the cultural norm these days is difficult to do in any meaningful way. So, the next several ePostcards will explore the prehistory, the Haida’s amazingly seaworthy canoes, and the extraordinary cultural and artistic depictions of a life path very much in tune with the natural world.

I became interested in Haida Gwaii when I read John Vallient’s book The Golden Spruce. Reading this and seeing these images has further inspired me … now I know I need to visit one day. Thank you!

Thank you all for your kind words! These comments help keep me inspired to continue writing. Sometimes, when I despair at the state of the world and the fragility of the environment we all depend on, I really need to hear from readers out there who enjoy these ePostcards. You are the wind in my sails!