ePostcard #167: A Naturalist’s Bookshelf (Eye of the Whale)

A NATURALIST’S BOOKSHELF

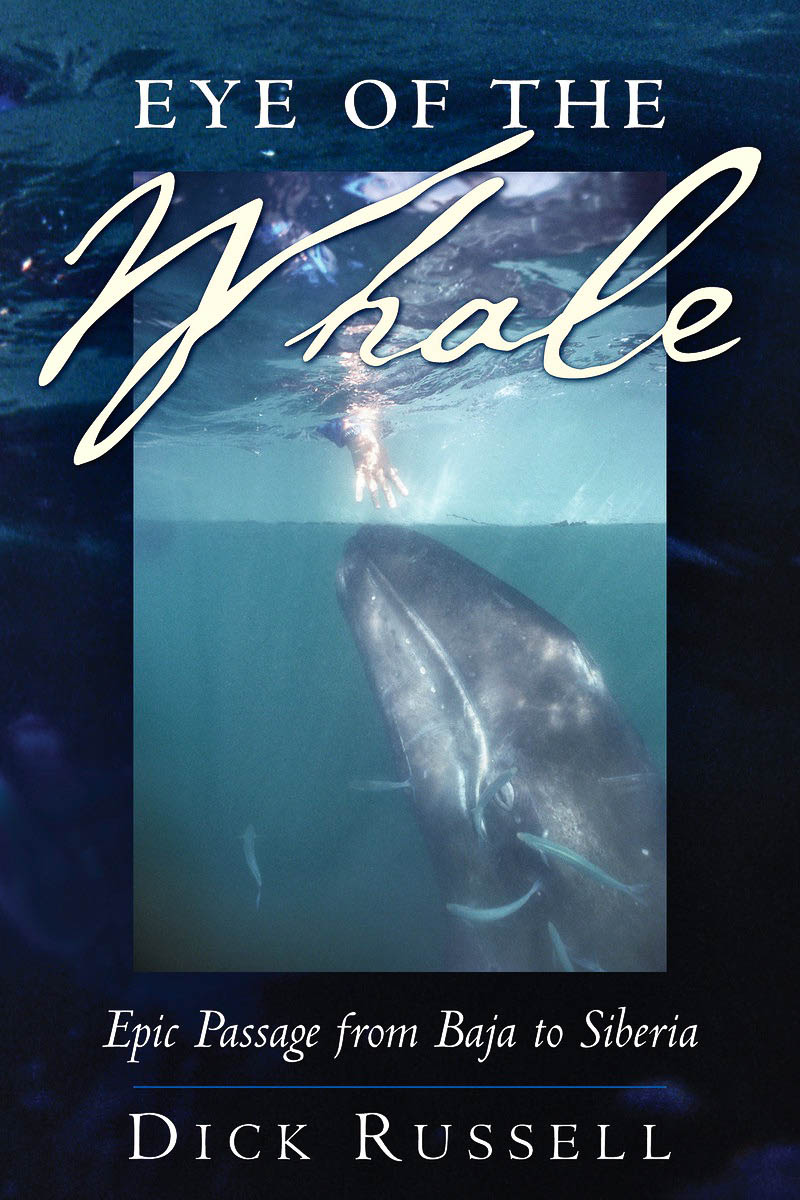

Photo Credits: All photos are courtesy of Audrey DeLella Benedict and are from Baja’s San Ignacio Lagoon, the winter home of he North Pacific gray whales. This is adult gray whale is giving us ‘the eye’ as it drifts alongside our panga.

BOOK OF THE MONTH

—Roger Payne, from Among Whales

EYE OF THE WHALE: Epic Passage from Baja to Siberia

Dick Russell (2001, Simon & Schuster)

Reprinted in 2004 by Shearwater Books/Island Press

Once you look—really look—into the eye of a whale you never forget the experience. The connection is profound and, for some, life changing. As a naturalist guide for the past four decades, I’ve been gifted with many extraordinary encounters with whales. Do I have a favorite whale species? This is an impossible question because whatever whale honors you with a glimpse of its life is certain to breach your consciousness in ways you might never imagine. I have just returned from my fourth visit to San Ignacio Lagoon, which is located halfway down the Pacific coast of Mexico’s Baja Peninsula, and is one of several lagoons along the peninsula where gray whales have been coming for thousands of years—to mate, give birth, and nurse their young within the sheltering embrace of these warm, shallow waters.

When I photographed this ancient petroglyph panel in the Sierra de San Francisco, deep within the mountains and far from the sea, I was stunned by the portrayal of a giant manta ray leaping out of the water and gray whale mothers and their calves swimming close together. This precisely pecked rendering on a canvas of sheer rock captured the moment and the movement perfectly, leaving no doubt that this memory was important to these indigenous peoples’ sense of place. I closed my eyes and tried to imagine what it must have been like for them, thousands of years ago, to see these lagoons and the whales for the first time, possibly on their own migration down the wild coast of the Americas. Whatever symbolic meaning this petroglyph panel held for the first people to live here, it clearly reflects their deep connection to the sea.

I read Dick Russell’s book, Eye of the Whale: Epic Passage from Baja to Siberia, after my very first trip to San Ignacio Lagoon. I wanted to learn everything I could about gray whales. What is it about looking into the eye of a gray whale, or any whale for that matter, that changes you? All I know about myself is that nature has been my touchstone in life. Not a deity I can’t get my mind around—just nature. Russell’s beautiful narrative is a tapestry woven broadly across the span of space and time—a reader’s voyage of discovery.

The book unfolds along the migratory route that gray whales follow each year as they leave their Baja breeding lagoons and head north to the food-rich Arctic waters of the North Pacific. We learn the unique aspects of gray whale natural history, their near extinction at the hands of commercial whalers in the 19th and early 20th centuries, the deluge of human-wrought, environmental threats they now face (including the uncertainties of climate change), and are introduced to the critical network of conservationists and scientists who have devoted their careers to understanding the lives of gray whales and other marine mammals.

Stepping back in time, we also meet Charles Melville Scammon, the whaling captain who became a naturalist and wrote The Marine Mammals of the Northwestern Coast of North America, and Herman Melville, the one-time whaler and the author of the great American novel Moby Dick. Both men exposed the harpoon-wrought devastation and havoc of commercial whaling in different ways, both books banishing any lingering hint of romanticism.

As a constant theme throughout the book, Russell explores the profoundly important and transformative shifts in human consciousness—an ongoing cultural and ecologically-based reckoning that acknowledges the role of humans in degrading the fabric of life that sustains us all. There is a luminous quality at the heart of Eye of the Whale—a ray of light and hope that makes this book a timeless reminder for us all!

Special Note: Dick Russell’s Eye of the Whale was honored as a Best Book of the Year by The New York Times, The Washington Post, and the Los Angeles Times upon its initial publication in 2001. Look online for used copies or check with your local library. It’s well worth the effort!

SAN IGNACIO LAGOON

When I imagine Captain Charles Melville Scammon, I see him standing at the helm of Ocean Bird, at the entrance to San Ignacio Lagoon, and scanning the horizon for the ephemeral sparkle of gray whale spouts. As I prepared for my most recent trip, I searched out a rare reprint of Charles Melville Scammon’s book, The Marine Mammals of the Northwestern Coast of North America, Described and Illustrated: Together with an Account of The American Whale-Fishery (1874). The long title of Scammon’s book suggests that this comprehensive natural history is the seminal work of a very complicated man—a self-educated marine mammal expert whose skills as an observer resembled those of Charles Darwin.

Many of the scientists interviewed by Dick Russell for his book were quick to point out that Scammon’s extraordinary volume was the first of its kind and paved the way for their own research. I wanted to understand why the natural history of marine mammals had become his enduring passion — without judging Captain Scammon for serving at the helm of whaling ships for 11 years. Sadly, his discovery of a navigable portal into one of the gray whales’ principal Baja spawning grounds did not go unnoticed among his whaling contemporaries. Rightly or wrongly, history has blamed Captain Scammon for single-handedly shifting the whaling industry focus to gray whales and pushing the species to the brink of extinction.

FRIENDLY GRAYS

The whales—they are my family.

Francisco “Pachico” Mayoral

HONORING FRANCISCO (PACHICO) MAYORAL

The experience of growing up near these magical lagoons, as Pachico Mayoral did, makes the sea a very real part of who you are. The sea shapes your life and how you make your living. How you balance what you take from the sea, and what you give back. Our modern-day encounters with gray whales in these lagoons are even more remarkable because of what their ancestors endured here historically at the hands of whalers. The gray whales were called ‘devilfish’ by the whalers because they were the most aggressive of all whale species in defending themselves and their calves. Even the bravest of whalers were afraid of adult grays because an attack could quickly turn deadly. Incredibly intelligent, grays learned to capsize the small whaling boats carrying the harpooners, most of whom couldn’t swim or were mortally injured when the whale smashed into their boat. The whaler’s wooden boats were no bigger than the fiberglass skiffs, called pangas, that are used today for whale-watching in the lagoons. Think about this when you read the story of Pachico’s encounter.

Walk along this broad swath of beach at San Ignacio Lagoon and you’ll see the storm-surge array of sun-bleached whale bones edging the high tideline. When I think about what friendly gray whale encounters have meant to me, I often re-read Dick Russell’s conversations with Francisco (Pachico) Mayoral, the fisherman who first experienced the ‘friendly’ approach of a gray whale in San Ignacio Lagoon. I want to share a bit of Pachico’s story of that 1972 encounter, in his own words, from Dick’s book:

“My partner, Luis Pérez, and I were fishing at Punta Piedra for grouper and Cabrillo. Suddenly, we were among many whales. Hundreds of gray whales swimming in this three-mile-long, one-mile wide inlet. They would not leave us alone. They would spy-hop on one side of the boat, raising their heads to look at us. Then they would go under the boat. At first, we were very scared.”

To put their feelings of fear in context, the men explained that a series of crosses mark the graves of several fishermen, who were steaming across the narrowest stretch of the lagoon when their panga accidentally crashed headlong into a gray whale. All the men died as a result of the crash. From that time onwards, fishermen learned to slow down and pound on the hull to alert the whales to stay at a safe distance.

“One of the whales was kind of scratching itself on the front of our little panga, and most of her body was underneath the boat, so we could not move. This continued for almost an hour. I couldn’t fish because we were using landlines, and I had to lift the line so I would not hurt the whale. Or else anything could happen. I don’t know what compelled me to reach out my hand. The moment I touched the whale for the first time, I felt something incredible. I lost my fear. I was amazed. It was like breaking through some invisible wall. And I kept touching. That moment I compare with when my first child was born.”

Pachico went on to explain that he believes that the whales are demonstrating friendship when they approach the pangas. From his perspective, it seems that the whales are very smart and showing humans how to live in some state of harmony with the world around them. This extraordinary man went on to become an ambassador for whales, the first Mexican to offer whale-watching tours in San Ignacio Lagoon and to provide logistical support for several of the leading gray whale researchers in the world. His three sons are all trained naturalists guides. I can sense Pachico’s hand and careful mentoring in the whale-sensitive ways in which the panga drivers and naturalist guides work together to ensure the best possible experience for both the whales and the visitors who come to see them.

The young gray whale (above and below) turned on its side as we watched so that it could see the driver of the panga (notice the dark disk of the eye on the opposite side from the blowholes).

To help build global awareness, we would appreciate it if you would share this post with your friends and colleagues. Please choose one of the options below which includes email and print! Thank you.

So beautifully said about how life-changing it is to look in the eye of a whale. I only experienced it once, at Limekiln Park on San Juan Island. I was down on the lower bank about 10 feet from the water when the Orca L pod came through; some swimming very close to the bank. One of them rolled on its side and made contact and looking into that eye and having it look back into me, I was transported to something timeless and ancient – a connection that we used to have with other intelligent, conscious, sentient creatures when we honored them as our brothers and sisters and valued what they had to teach us. I felt I was looking into the eye of a sage -all knowing and wise in its Is-ness. That kind of conscious contact is beyond anything I ever felt with another human.

Thank you for writing about the grays. and for your always wonderful photography and the book recommendation – I’ll look for it. I hope I see the grays while I am still on this earth. I am deeply concerned about the plans to drill in the Arctic and/or make massive export routes with the huge tankers to go through the Chukchi Sea. I wish and hope and pray we can stop it.

Sadie, as always, thank you for your beautiful words. I’ll hope we get to meet each other one of these days!