ePostcard #168: There She Blows!

Photo Credit: Courtesy of Audrey DeLella Benedict. A mother gray whale and her calf rest and breathe at the surface in Laguna San Ignacio.

THERE SHE BLOWS!

“All my means are sane, my motive and my object mad.”

― A reckoning quote from Captain Ahab in

Herman Melville’s novel Moby Dick

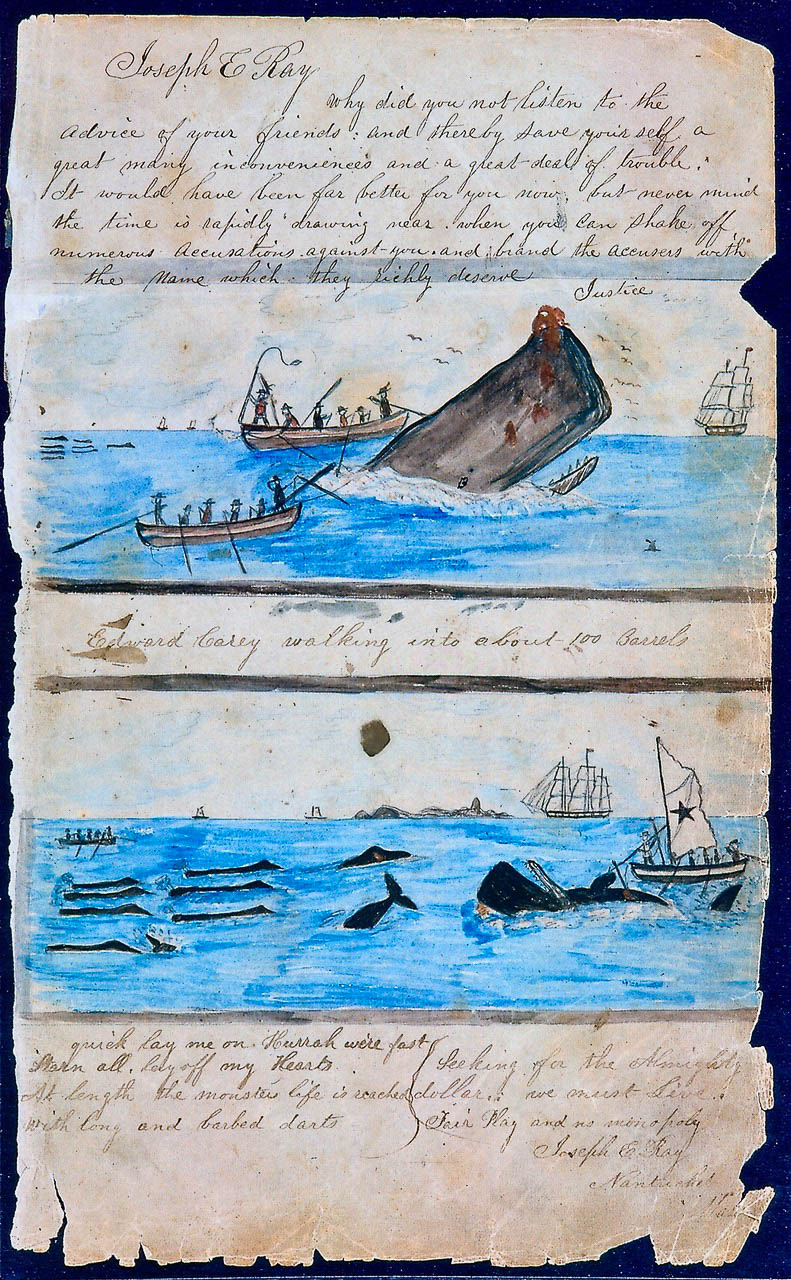

Illustration Credit: This page, courtesy of the NPS and the New Bedford Whaling Museum, is from Nantucket Captain Joseph Ray’s whaling logbook.

In early December of 1846, the American whaler Hibernia, with Captain Smith at the helm, sought a safe anchorage beyond the reach of a fierce winter storm and sailed into the entrance of Bahía Magdalena along the west coast of the Baja Peninsula. The bay was exactly as described in the ship’s logs from previous voyages. The sandy barrier islands of Isla Magdalena and Isla Santa Margarita effectively buffered the bay from the vast fetch of the Pacific Ocean, and the mountainous backbone of the Baja Peninsula blunted the passage of storms from the east. Magdalena Bay, in fact, was well-known as early as 1837 by Pacific whalers who took advantage of the bay for temporary layovers to cooper (repair) their oil barrels and as a brief staging area for hunting migrating sperm whales.

Setting anchor firmly in the mud-bottomed seabed, Captain Smith made the decision to rest his crew and take advantage of the layover to repair the whale boats and gear that should give them a head start on the spring whaling season. The men would certainly welcome a break from the rigors of shipboard life, and they’d be able to gather driftwood ashore, catch fish and sea turtles, and harvest oysters in the mangroves to replenish the ship’s food stores.

At dawn, crew members woke to sunshine and gathered on the foredeck to await their captain’s orders. As was normal procedure on anchor watch, a crew member climbed the foremast rigging to the crow’s nest to scan the horizon for other ships or unforeseen dangers. Without uttering a sound, the lookout quickly got the men’s attention and pointed west. A light breeze was already magnifying the distant but unmistakable sound of whale spouts, the cetacean background score for what turned out to be an armada-like procession of gray whales entering the bay. The whalers had never seen so many grays together like this before. They had discovered, purely by the accident of their timing, one of the major overwintering birthing and breeding grounds for the gray whale.

As we now know, the eastern Pacific population of gray whales migrates south along the coast in autumn to their winter breeding grounds along the west coast of Baja California Sur (Mexico) and the southeastern edge of the Gulf of California. It is entirely possible that the whalers arrival in the bay coincided with the leading edge of the southbound grays’ migration to their winter home. Sensing a windfall of opportunity, the captain ordered the men to quietly lower the whaling boats and the harpooners began their deadly work.

Gray whales have the longest migration of any mammal on Earth, traveling between 10,000-12,000 miles round-trip each year from their Arctic feeding grounds to their overwintering and breeding grounds along the Baja Peninsula. Recent telemetry reports of humpback whale migrations are catching up. Grays are considered the most ‘primitive’ whale, which simply means that they’re most like the common ancestor of all whales, and they’re the only whale species to traverse the comparatively shallow waters of the continental shelves.

For thousands of years, gray whales have congregated in large numbers during the months of December to April in three shallow, warm-water lagoons along the Baja Peninsula: Bahía Magdalena, Laguna San Ignacio, and Laguna Ojo de Liebre (known by Americans as Scammon’s Lagoon). In these sheltered waters, the whales are able to give birth, nurse their calves and mate without fear of predators. Sadly, that situation may be changing as reports of marine mammal-eating killer whales making successful predatory forays into the lagoons are increasing. Killer whales and humans have long been the gray whales only predators in the open ocean.

During the heyday of deep-water whaling, gray whales were not a commercially prized species. The blubber from a single gray yielded no more than forty barrels of oil—half the yield of a sperm whale or a bowhead; and their blubber was dark colored when rendered and their baleen was too coarse to be used commercially as whalebone for corsets and buggy whips. As the whalers would soon learn, hunting the gray whale had its advantages.

Most large whale species, retreating in late fall from their summer feeding grounds in the polar seas, steered clear of the relatively shallow coastal waters on the Continental Shelf and headed instead for off-island breeding grounds in the open ocean: the Azores, Madagascar, or Micronesia. As a result, whalers were forced to pursue the deep-water species, which were faster and larger than their own ships, through storm gales, dead calms, and uncharted seas. The gray whale, on the other hand, headed south along a 6,000 mile and somewhat predictable route from the Arctic to breed in the warm coastal lagoons of Baja California, an almost idyllic hunting setting by whaling standards.

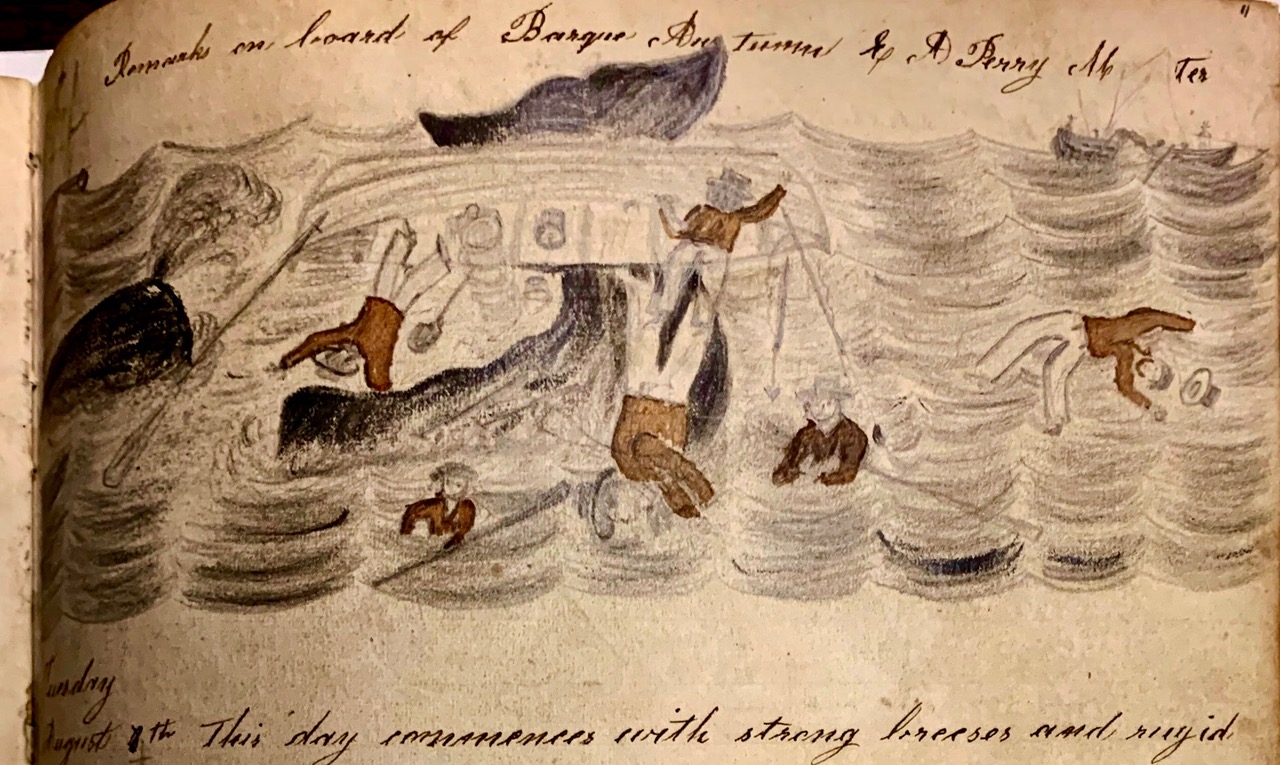

Illustration Credit: Courtesy of The Clements Library (University of Michigan). The Clements Library acquired a volume of extracted whale log entries from the Barque Autumn. This page from the captain’s whaling “abstract logbook” documents events during a voyage from Stonington, Connecticut, to the Indian Ocean and South Pacific between 1845 and 1849. Captain Edwin Augustus Perry commanded the vessel. Abstract logs are portions of the full logbook recorded as a separate volume, a condensed linear narrative of all instances of the crew’s encounters with whales. The risks to life and limb were a daily reality for whalers, and this page from the captain’s logbook records the flipping of a whale boat and its crew by a sperm whale. The whales on the receiving end of the harpoon, when finally cornered, were not passive in accepting their fate.

At sea, a harpooned whale tended to run and “sound,” that is, dive for the bottom, in the hope of shaking loose the whaleboat at the end of the harpoon line. The shallow waters of the Baja lagoons thwarted this tactic and forced gray whales to meet their human adversaries head on. Since the grays could maneuver much more quickly than the whaleboats, their pursuers often found themselves to be the object of a counterattack by an angry gray. Wounded whales sometimes cornered their tormentors in the shallows, up-ending the whaler’s boats or ramming them with their heads until the boats broke into pieces. In the havoc that ensued during such an attack, crew members were often seriously injured or might die in the mêlée by drowning.

The gray’s most deadly tactic was “lob-tailing,” a maneuver in which their powerful flukes would clear the water in a classic arc and then come crashing down on the luckless crew in the whaling boat. Deep-water whale species resorted to these counter offensive only occasionally, but the lagoon-confined grays had to rely on what Charles Melville Scammon would later refer to as their “sagacity” in adopting successful defensive strategies.

Photo Credits: All historic photographs are courtesy of the National Park Service and New Bedford Whaling Museum. The first shows lookout crew members on the crow’s nest platform. The second shows men overboard after their whaleboat is stoved in by a sperm whale (1922). The third shows crew members rendering blubber for oil onboard their ship. The fourth shows hundreds of barrels of whale oil offloaded on the dock in New Bedford, Massachusetts.

To help build global awareness, we would appreciate it if you would share this post with your friends and colleagues. Please choose one of the options below which includes email and print! Thank you.

What a great article; thanks for sharing.

David Attenborough: “Our blind assault on the planet has now come to alter the very fundamentals of the living world.”

Reading this post card and have watched a documentary about the fate of the turtles trying to survive the oceans full of plastic, paints a very grim picture what we are doing to the natural world.