ePostcard #91: Tierra del Fuego: The View from Space

ePostcard #91: Tierra del Fuego: The View from Space

I am the albatross that waits for you

at the end of the world.

I am the forgotten souls of dead mariners

who passed Cape Horn

from all the oceans of the earth.

But they did not die

in the furious waves.

Today they sail on my wings

toward eternity,

in the last crack

of Antarctic winds.

Chilean Poet: Sara Vial

Note to Readers: Our next few ePostcards will explore the natural and human history of this amazing archipelago. They will also set the stage for our next ePostcard series, which features natural history highlights from multiple Cloud Ridge Naturalists’ explorations along both the Atlantic and Pacific coasts of South America—“In Darwin’s Footsteps.” These incredible trips would have been impossible without the guiding expertise, logistical support and collaborative efforts of my Argentinian naturalist friends and colleagues, Carol and Carlos Passera, and their company Causana Viajes.

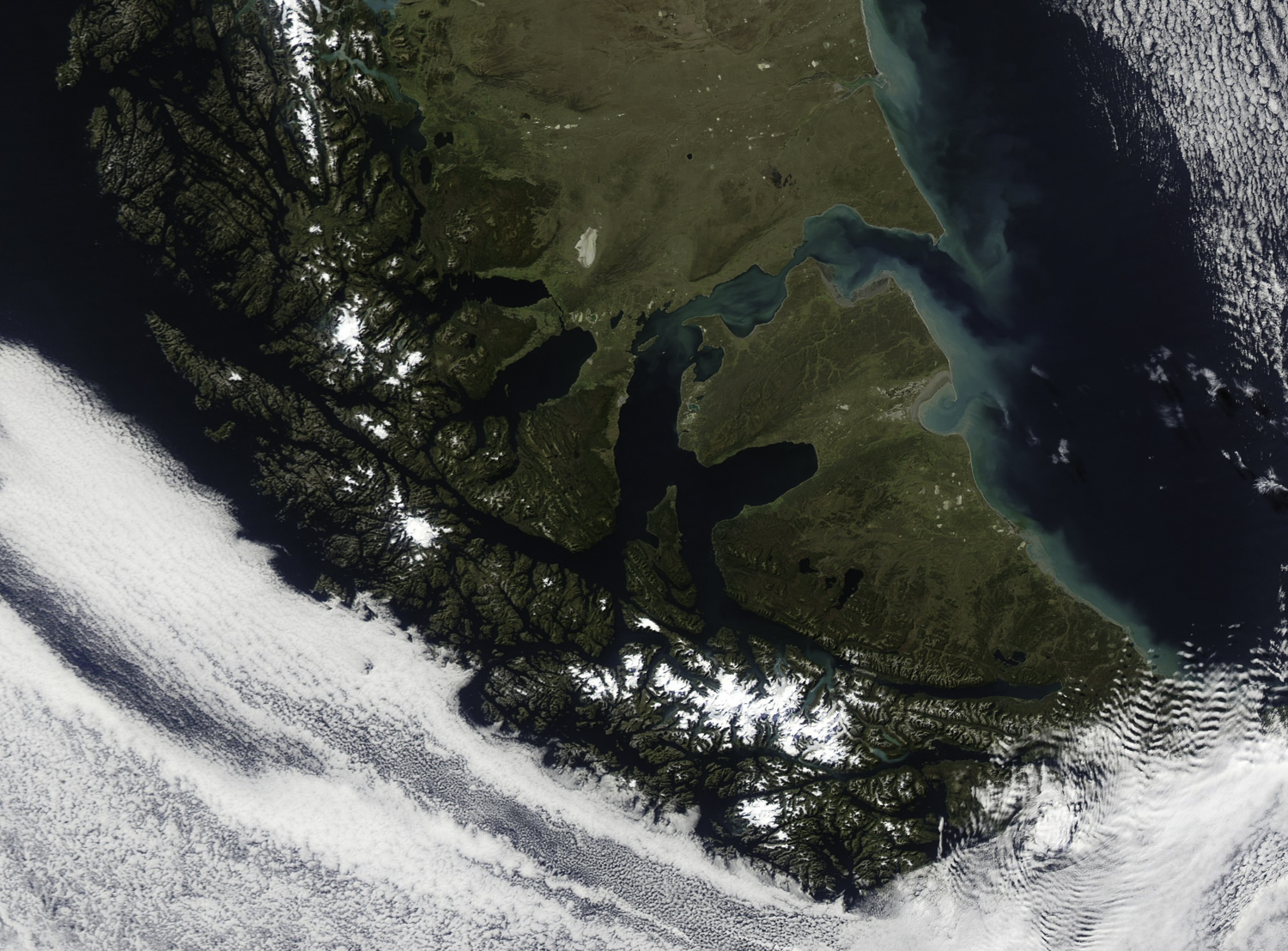

This NASA satellite photograph of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago gives us a “space-eye” view of one the most extraordinary wilderness regions on Earth—the southern tip of the South American continent. The pale green swirls you see as you move up the Atlantic coast of Tierra del Fuego reveal an austral spring “bloom” of phytoplankton (diatoms and other photosynthetic microorganisms), which form the all-important base of the marine food web. As you follow the green swirls inland, you have entered the legendary Strait of Magellan, the 350-mile navigable passage between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans located at the southern extremity of South America. The strait separates the mainland (Argentinian and Chilean Patagonia) from the archipelago of Tierra del Fuego, the eastern part of which today belongs to Argentina, the western and southern parts, including Cape Horn and its surrounding islands, to Chile.

When Ferdinand Magellan (Fernão de Magalhães) set sail from Spain in 1519 with five ships, he had been charged by King Charles I with discovering a commercial route to the Spice Islands via South America, and securing exclusive European rights to the spice trade. At the beginning of his journey, his contemporaries suspected it was impossible to sail around the entire globe—and feared that everything from sea monsters to killer fogs awaited anyone foolhardy enough to try. Magellan’s discovery in 1520 of the strait that would later bear his name and his expedition’s ultimate circumnavigation of the world has become one of the greatest exploration stories of all time. For mapmakers, the true size and scope of the planet had been revealed. There was, indeed, a passage to the Pacific, and a vast uncharted ocean now awaited the pursuit of European explorers. I’ll devote our next ePostcard to the story of Magellan’s voyage and the sad legacy of European adventurism and greed in the New World.

As you look down on the snowy mountains and glaciers (near the photo’s center), note the slender linear waterway crossing diagonally from east to west below the largest snowy range—this is the Beagle Channel (named in honor of the HMS Beagle), a 700-foot-deep glaciated gouge that links the Atlantic to the Pacific. Isla Navarino forms the southern shore of the Beagle Channel, and is claimed by Chile. Where the channel opens into the Pacific, it endures the full brunt of westerly storms, splintering into a maze of largely uncharted fjords. Standing on the deck of the HMS Beagle as Captain Fitzroy approached the channel’s western entrance, Charles Darwin would later describe watching in awe as the waves exploded against the 200-foot high cliffs. In contrast to the perilous, fjord-riven west coast of Tierra del Fuego, the Atlantic coast lures the unwary with the promise of benign seas. The alpine ranges between the Pacific Ocean and the modern city of Ushuaia tend to dampen the power of the hurricane-like storms before they reach outer coast. With its high sides and east-west axis, the Beagle Channel is a natural wind tunnel and gusts of up to 100 knots aren’t a rarity. The influence of wind is etched on the landscape, with beech trees restricted to the lee side of ravines and ridges, and those exposed are permanently bent to leeward.

The wind-rippled clouds (photo #1, lower right corner) obscure our view of Tierra del Fuego’s southernmost islands, including Isla Navarino, Isla Hoste, Isla Horno and Islas Diego Ramírez, and the infamous high seas of the Drake Passage. I have provided two maps (photos #2 and #3) to help with the geography. Cape Horn marks the southern headland of Horn Island, Chile, the southernmost island in the archipelago. The “horn” is essentially a wind-ravaged outcrop of basalt—the infamous “rock in the stream”—where the Atlantic, Pacific and Southern Oceans collide in a tempestuous maelstrom. No land to the east, none to the west—and the winds sweep all the way around the world from the west. The closest arm of Antarctica, Graham Land of the Antarctic Peninsula, lies 600 miles to the south across the roughest stretch of water known on the planet, Drake Passage. I have personally experienced both “Drake Lake” (totally becalmed) and “Drake Hell” (30-35-foot waves) and thanked my lucky sea legs both times!

Cape Horn lore is full of fear and fascination—best expressed in the old sailor’s motto: ‘Below 40 degrees south there is no law and below 50 degrees south there is no God’. In the Southern Ocean, these descriptive terms—Roaring Forties, Furious Fifties and Screaming Sixties—refer to the ever-increasing wind speeds that marine navigators experience with every 10 degrees of latitude as you get closer to Antarctica. These latitudes are notorious for their ferocious storms and powerful westerly winds, and for waves that can build up to the size of a six-story building!

How do these winds form? The circulation of wind in the atmosphere is driven by the rotation of the Earth and incoming energy from the sun. This process sets up global circulation cells, the driving force behind global-scale wind patterns. Wind circulates in each hemisphere in three distinct cells, transporting energy and heat from the equator to the poles. The Roaring Forties take shape as warm air near the equator rises and moves toward the poles. Warm air moving poleward (on both sides of the equator) is the result of nature trying to reduce the temperature difference between the equator and at the poles created by uneven heating from the sun. The Roaring Forties in the Northern Hemisphere don’t pack the same punch that they do in the Southern Hemisphere, largely because the large land masses of North America, Europe, and Asia obstruct the airstream. In the Southern Hemisphere, there are far fewer land masses to interrupt or deflect the winds in South America, Australia, and New Zealand.

Since its discovery by the Dutch mariners Jacques Le Maire and Willem Corneliszoon Schouten in 1616, Cape Horn has become known as the graveyard of ships. Cape Horn was once a critical part of the clipper ship routes that transported much of the world’s trade, marking a gateway between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. As ships got larger, they could not navigate the Strait of Magellan and had to risk “rounding the Horn,” a phrase that has acquired almost mythical status. Over the past four hundred years, the Horn’s cold, tempestuous waters have claimed more than 1,000 ships and 15,000 lives. Even successful passage has often exacted a toll. For example, Captain William Bligh on the HMS Bounty tried for a month in 1788 to round the Horn on his way to Tahiti, but adverse weather forced him to turn around and take the longer route east past Africa and India instead. During the Age of Sail (circa 15th to 19th centuries), these winds propelled ships across the Pacific, often at breakneck speed. Nevertheless, sailing west into heavy seas and strong headwinds could take weeks, especially around Cape Horn at the southern tip of South America, making it one of the most treacherous sailing passages in the world. Since the opening of the Panama Canal in 1914, there has been no need for most commercial ships to run the risk anymore, though adventuring ecotourists, sailors and yacht racing enthusiasts continue to test their luck.

Credit (photo #1): Overview of Tierra del Fuego; Courtesy of NASA.

Poem: In 1992, a monument to the memory of the mariners lost in the waters off Cape Horn was erected on Horn Island (Isla Horno), financed with both public and private funds from Chile and many other countries. The interior outline of the monument’s facing steel sheets form the image of a wandering albatross in flight; a nearby marble plaque is inscribed with the albatross poem (above) by Chilean Sara Vial. (photo #4)

Credit (photo #2; Audrey Benedict): Tierra del Fuego National Park.

Map (photo #3): Geopolitical map of Tierra del Fuego (open source map)

Map & Caption (photo #4): In October 2017, the Government of Chile announced the creation of a marine park that will protect 45,000 square miles of Chile’s southern waters, starting at Cape Horn and encompassing the Diego Ramírez archipelago. This marine park, which includes the southernmost inhabited island outpost in the Americas, will help to protect some of the last remaining intact subantarctic ecosystems, marine mammals (seals, sea lions, and whales) and a diversity of seabirds and their nesting grounds, including black-browed albatrosses, rockhopper penguins and about 80 percent of the world’s population of blue petrels.The waters surrounding the Diego Ramírez host an extraordinarily biodiverse ocean ecosystem that includes the world’s southernmost giant kelp forests. These kelp forests are so dense that they can be seen from satellite images.

Credit (photo #5): Memorial monument atop Cape Horn.

Credit (photo #6): Jordi Planamor; THEMAFOTO2, Crossing the Drake Passage (Dutch Tall Ships)

Credit (photo #7): Watercolor illustration of the HMS Beagle off Cape Horn by Mark Richard Myers, National Geographic

click images to enlarge

click images to enlarge

To help build global awareness, we would appreciate it if you would share this post with your friends and colleagues. Please choose one of the options below which includes email and print! Thank you.

Audrey, Your text and photos are extraordinary. So glad you will continue with another ePostcard series.

Mike, my thanks for your kind words! I’ve been challenged by some medical issues over the past few months that slowed down my ePostcard work. I took a few days off to read and reorganize my thoughts for the shift north to South America. I’m back on track and looking forward to at least another year of ePostcards!

Audrey, I am sure you remember the first time we were standing on the shore of the Strait of Magellan, and I kept asking you to pinch me, that feeling was present when we returned there the second time just 2 years ago. I remember as a young school girl in Tehran reading and learning about Magellan and his discoveries. For some reason it sounded dreamy, magical and out of reach and yet you took me there twice. So huntingly beautiful so other worldy . I loved reading this blog and refresh my memory of some of the history … and Drake passage.. I will never ever forget that crossing!

THANK YOU.

Oh one more thing , loved the poem you have chosen for this blog. Just perfect.