ePostcard #41 (Mawson’s Australian Antarctic Expedition (1911-1914)

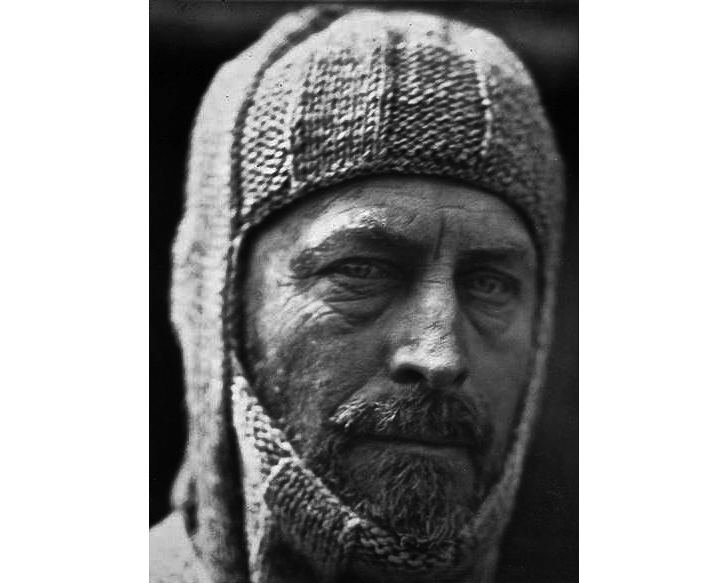

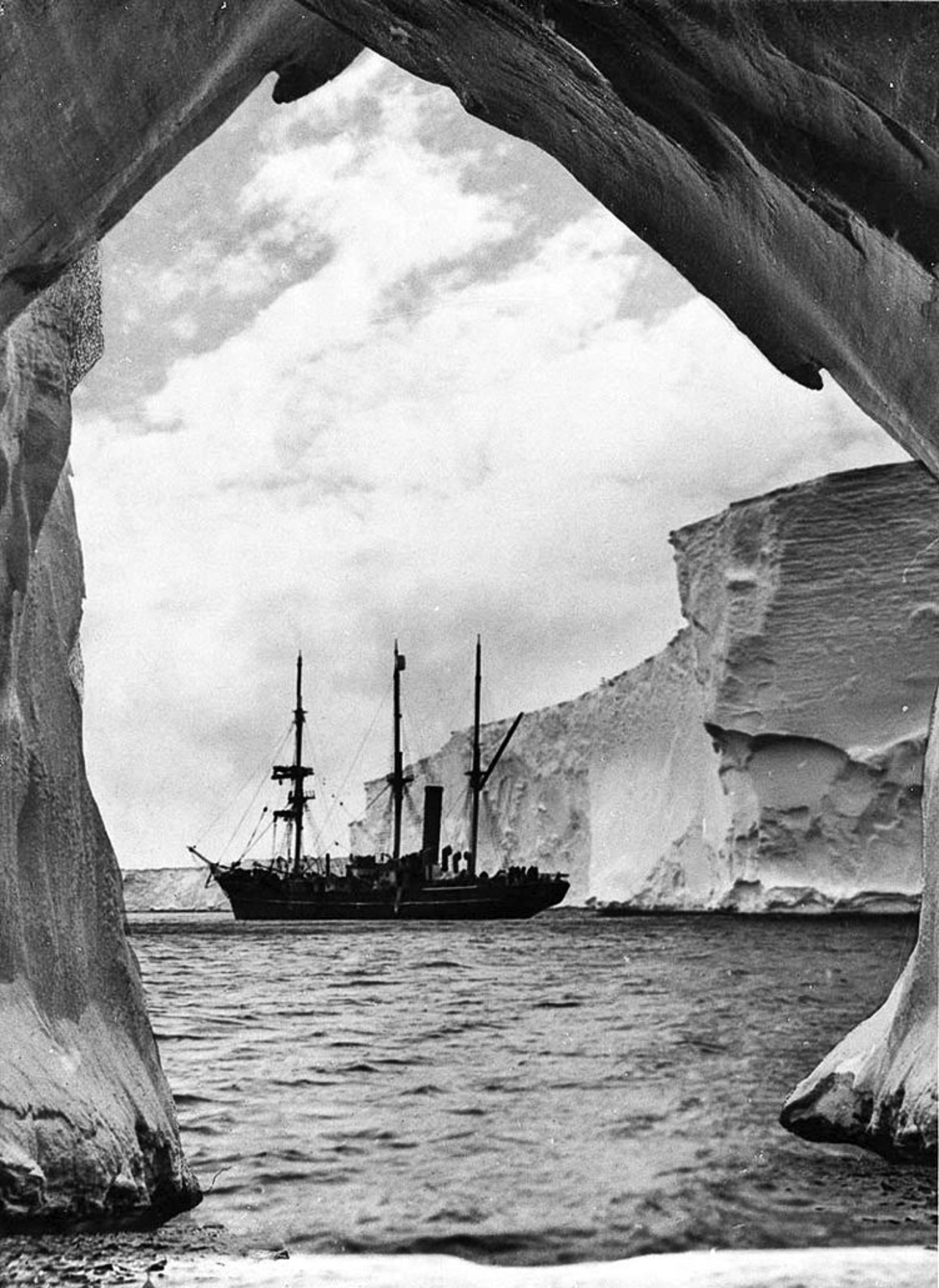

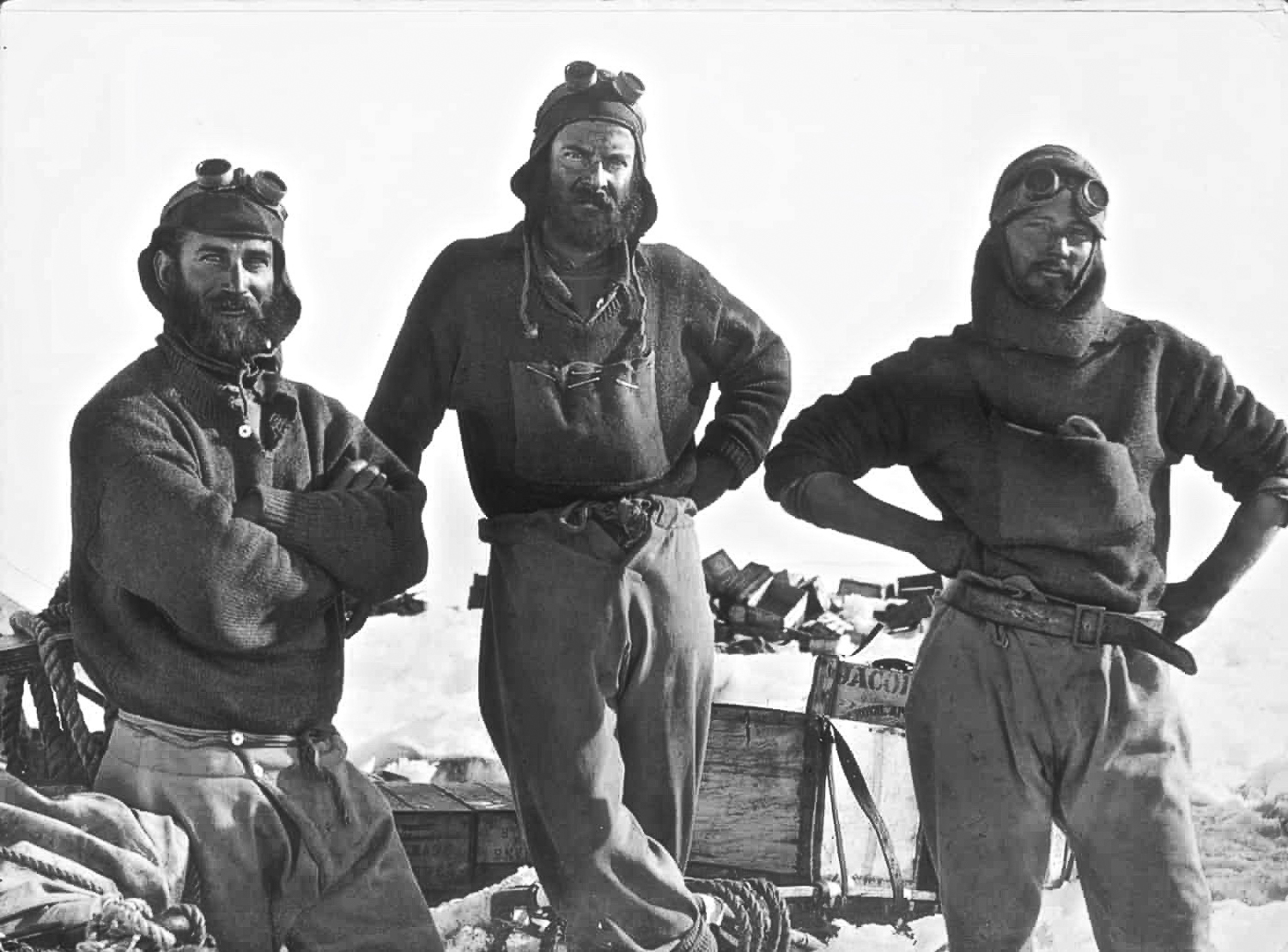

Dedication and Biographical Notes: This ePostcard is dedicated to the extraordinary Antarctic exploration legacy of Sir Douglas Mawson (above) and expedition photographer Frank Hurley (photo #3, center). All the photographs you see here are Frank Hurley’s.

Sir Douglas Mawson (1882-1958) was an Australian geologist, Antarctic explorer, and professor of geology. Along with Amundsen, Scott, and Shackleton, Mawson was a key expedition leader during the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration. Mawson proved his mettle with his first Antarctic experience, when he was chosen as the geologist with Ernest Shackleton’s 1907-1909 British Antarctic Expedition (Nimrod). On that expedition, Mawson completed the longest Antarctic man-hauling sledge journey ever undertaken (122 days) and was one of the team to first climb Mount Erebus and to reach the Magnetic South Pole. Undaunted by hunger, hidden crevasses, frostbite and exhaustion, the team returned home to a hero’s welcome. Douglas Mawson returned to his university post in Adelaide in 1909 and immediately began planning his own expedition to Antarctica to chart the Antarctic coastline directly south of Australia, turning down a place on Scott’s British Antarctic Expedition to the South Pole. The story of the Australian Antarctic Expedition defined Mawson’s place in Antarctic history. The Mawson Station in the Australian Antarctic Territory is named in his honor.

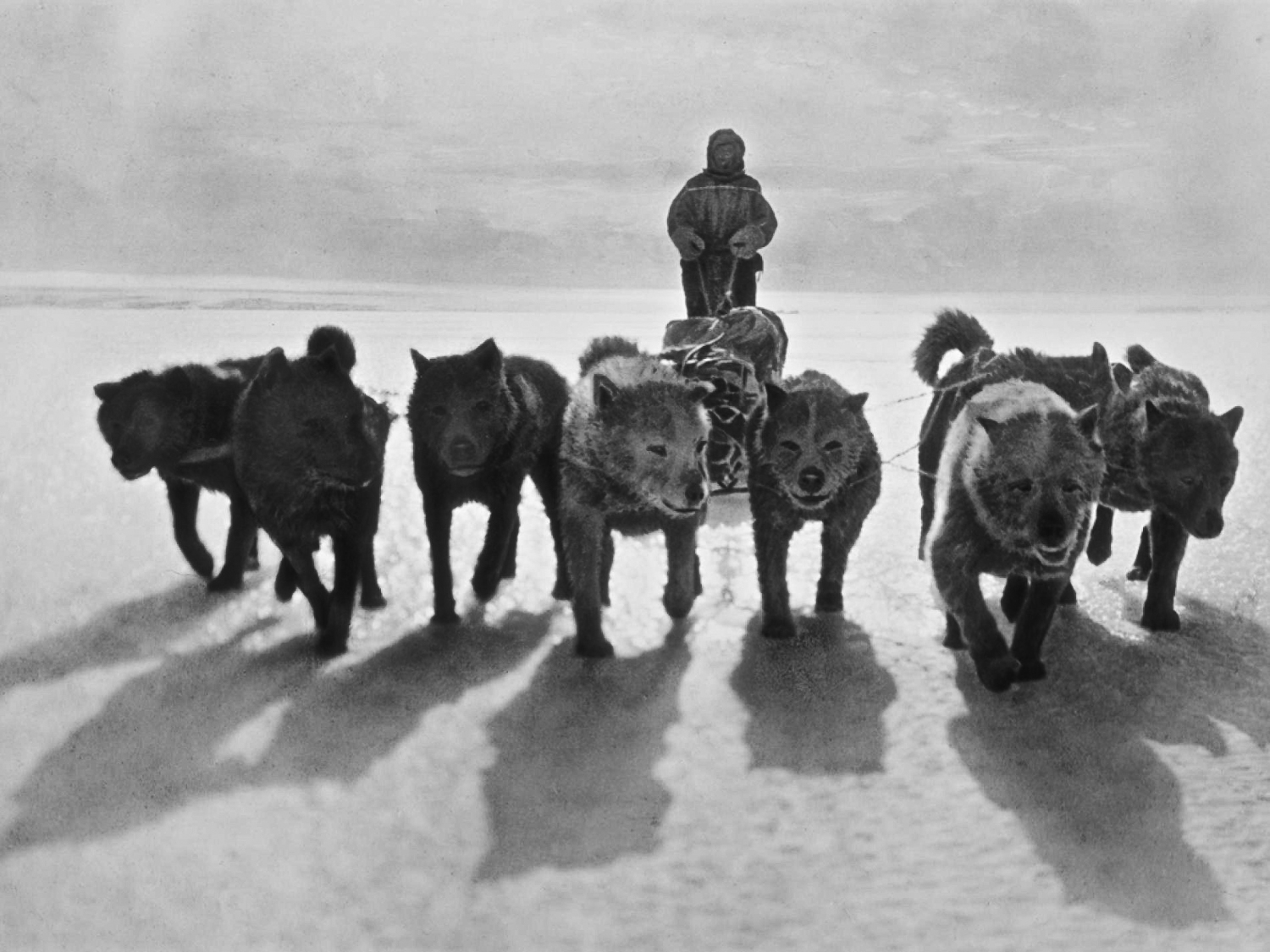

James Francis “Frank” Hurley (1885-1962) was an Australian photographer and adventurer. In 1908, at the age of 23, Frank Hurley learned from his mentor, Henri Mallard, that Australian explorer Douglas Mawson was planning an expedition to Antarctica. Hurley sought out Mawson directly to apply for the job as expedition photographer. Hurley’s passion and Mallard’s recommendation earned him the job. Mallard, who operated the first Kodak franchise in Sydney (to which Hurley was in debt), would ultimately provide the photographic equipment for the expedition. Among many exceptional images, Hurley’s motion pictures of expeditioners being driven backwards by the katabatic winds at Cape Denison captured the day-to-day hardships and heroism of life in the Antarctic. He used a hand-crank movie camera, the Debrie Parvo L 35 mm, to document expedition activities. He also took part in a record-breaking sledging journey to locate the South Magnetic Pole (averaging about 41 miles/66 km a day), filming key events along the way. Frank Hurley would spend more than 10 years in the Antarctic as the photographer for several Antarctic expeditions and also served as the official photographer with Australian forces during both world wars. He understood the magic of light in photography and his artistic style produced many memorable images, some of which he “ staged” or created from combining images in the darkroom. I encourage you to find a copy of the book “South With Endurance: The Photographs of Frank Hurley” (Bloomsbury, 2004).

To grasp the full magnitude of the extraordinary story of the Australian Antarctic Expedition, you need to read Mawson’s book “Home of the Blizzard.” I can’t do justice to either the heroism, the tragedies or the achievements in an ePostcard. Decades ago my late husband, Jim, gave me a First Edition copy of Mawson’s book (dated 1930) and the expedition’s story has haunted me all these years. After our first landing at Mawson’s Hut in 2006 was cut short a blizzard, I had a dream that night that I remember quite clearly. Perhaps it was the combination of opioids and wine prescribed by the New Zealand doctor for my broken ribs, but my dream allowed me to look through the hut window as Mawson’s men gathered around him after he had returned alone to the hut in February 1913. Whatever I write seems a trivial rendering of their story—so, forgive my attempt below and read Mawson’s “Home of the Blizzard” for yourself.

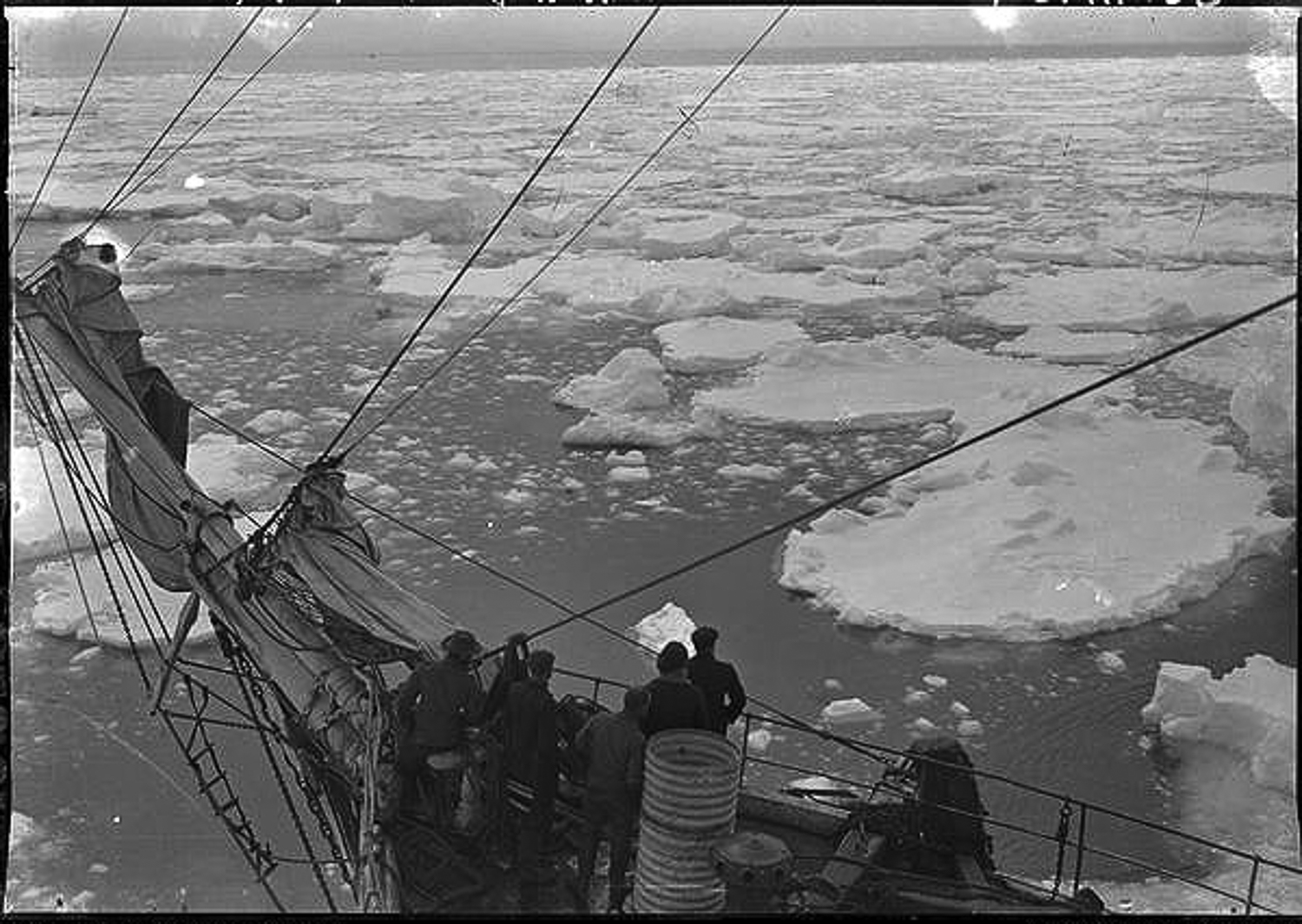

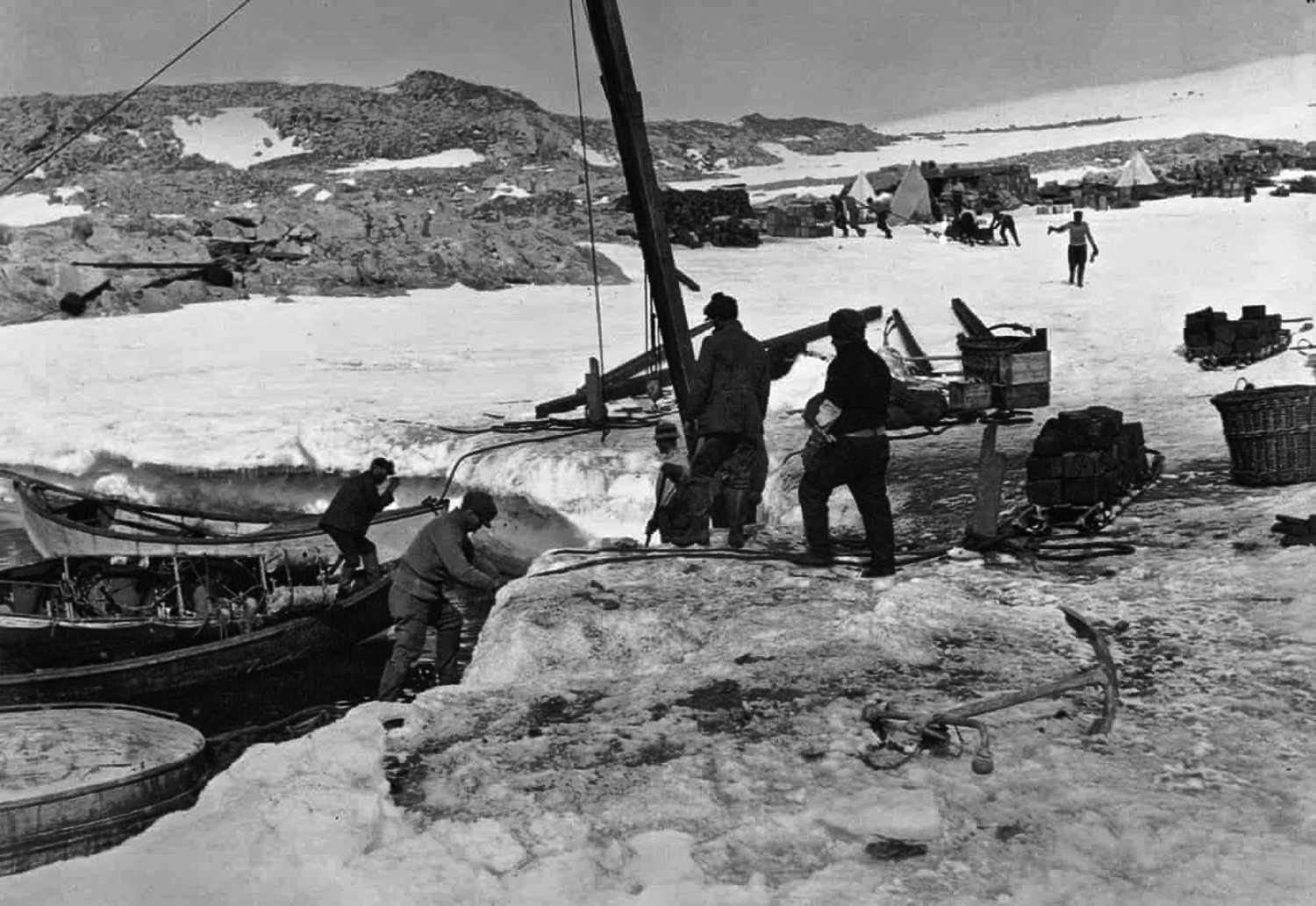

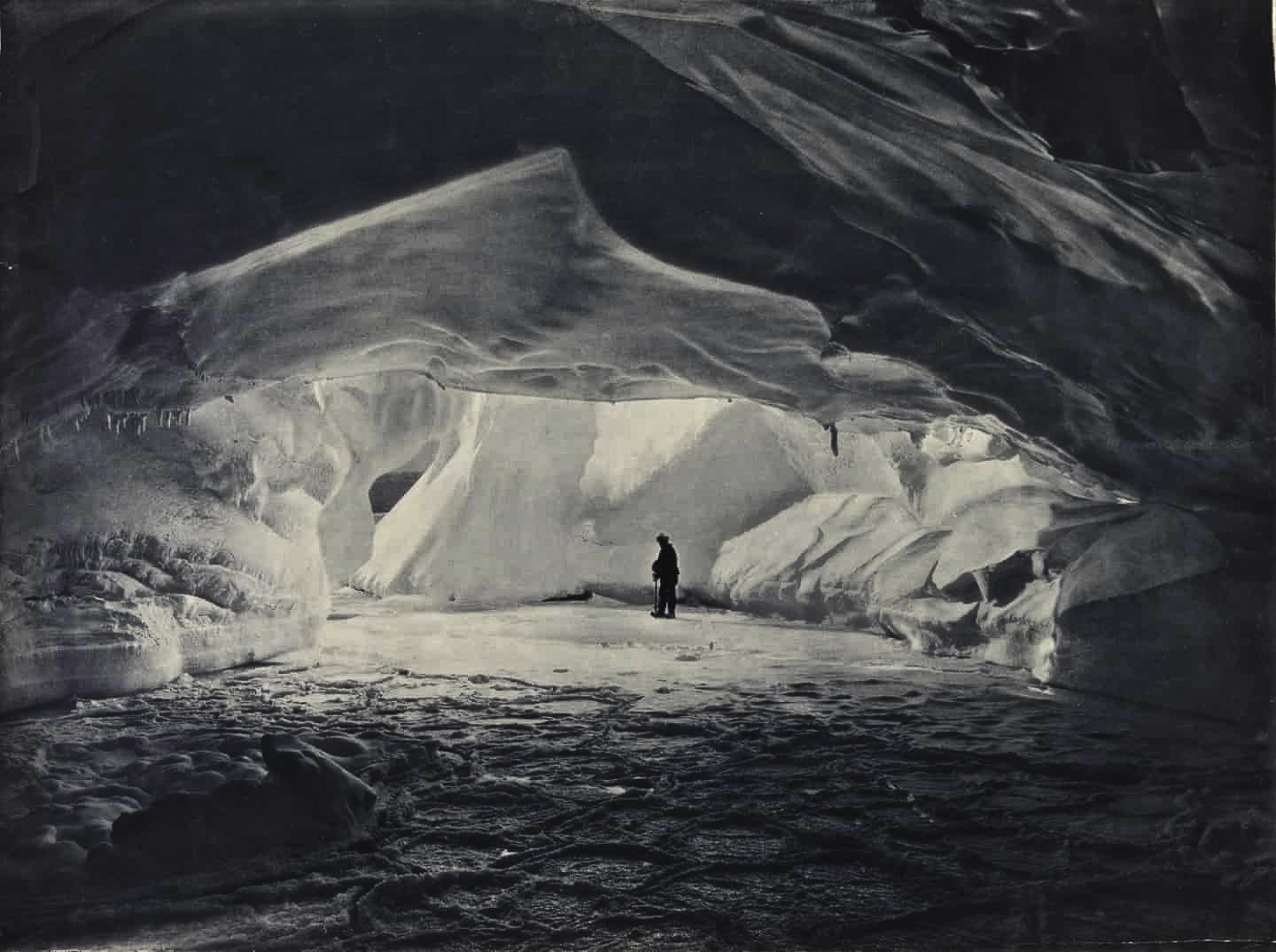

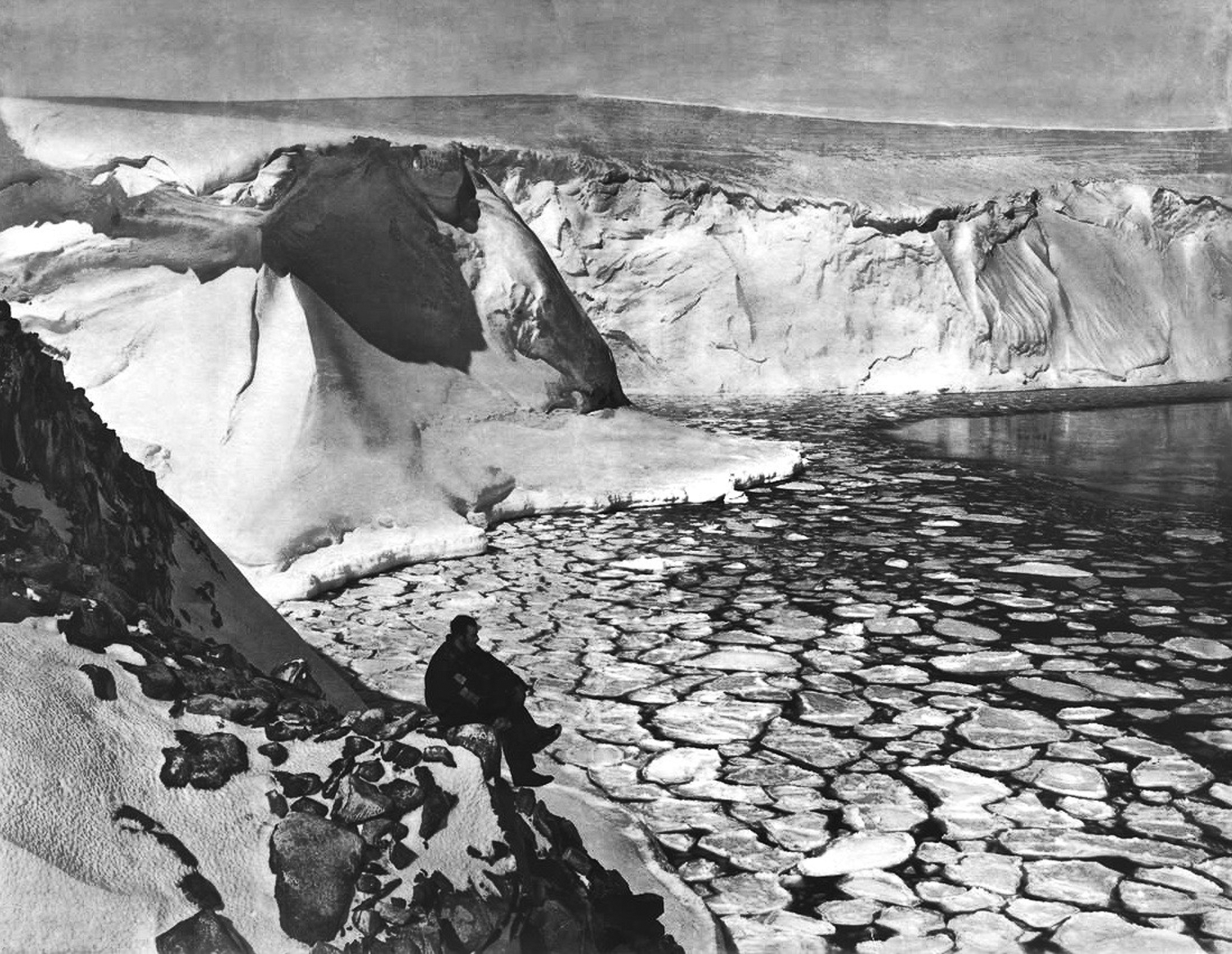

Into the unknown—31 men at the bottom of the world exploring uncharted territory. Given Mawson’s spirit and passion for science, I can only imagine what he might have been thinking as stood on the bow of the supply ship Aurora as they approached Cape Denison. Only 30 years old, uninterested in joining the race to the South Pole that so obsessed Scott, Shackleton and Amundsen, Mawson’s goal was to explore an unknown 2,000-mile-long (3,200 km) swath of the southern continent and to bring back the best scientific results yet to be wrung from Antarctica. Sailing from Tasmania, the Australasian Antarctic Expedition established three bases in Antarctica; one on Macquarie Island, one at Cape Denison and one on the Shackleton Ice Shelf at Queen Mary Land, each with the aim of carrying out survey and exploratory work as well as extensive scientific research. Building their research base hut (Mawson’s Hut) on the shore of a cove they named Commonwealth Bay, the men experienced their first winter in what was later proven to be the windiest place on Earth. At times, the gales were so strong they knocked the men off their feet and sent them sliding across the ice.

In November 1912, Mawson’s sledging party, one of eight teams with three men each, set off to explore in all possible directions from their base hut. Mawson chose 29-year-old Swiss ski champion Xavier Mertz and 25-year-old Belgrave Ninnis, a determined Englishman serving in the Royal Fusiliers, for his sledging team. Mawson’s party intended to make the deepest push into the unknown, connecting the unmapped interior with far-off Oates Land, which was discovered by Scott’s party only the year before. What ultimately happened to Mawson, Mertz and Ninnis remains one of the most powerful but also terrifying sagas of exploration. Alone and long overdue, Mawson limped and crawled down the final slope towards the base hut on February 8, 1913—only to see the Aurora well underway back to Australia. He had missed the Aurora’s necessary departure from Commonwealth Bay before the winter’s sea ice closed in by five hours. Thinking himself abandoned, he was stunned when the six men who stayed behind to mount a search party spotted him on the horizon. As the men rushed up the icy slope and embraced the gaunt, ravaged man who staggered toward them they could barely identify their leader. Ten long winter months passed before the Aurora could return to retrieve the men.

The Australian Antarctic Expedition had achieved the impossible, exploring almost four thousand miles of land, outlining the geology of the country, identifying the characteristic features of the continental ice shelf, discovering new biological species on land and at sea, recording meteorological data simultaneously at three bases, making field observations to define the location of the South Magnetic Pole, the first to use radio communication in Antarctica, and finding the first meteorite in Antarctica. When Mawson finally got back to Australia in February 1914, he was greeted as a national hero and knighted by King George V. Although Douglas Mawson spent the rest of his career as a professor at the University of Adelaide and led two more Antarctic expeditions, his life’s work became the production of 96 published reports that embodied the scientific results of the Australian Antarctic Expedition.

If you would like to view more video, please follow these links:

The Home of The Blizzard

https://www.youtube.com/watch?

Australian Screen

Australian Screen is part of the National Film and Sound Archive of Australia

Clips from Home of the Blizzard 1998

https://aso.gov.au/titles/documentaries/home-blizzard-1998/clip1/

https://aso.gov.au/titles/documentaries/home-blizzard-1998/clip2/

https://aso.gov.au/titles/documentaries/home-blizzard-1998/clip3/

To help build global awareness, we would appreciate it if you would share this post with your friends and colleagues. Please choose one of the options below which includes email and print! Thank you.

I’ve been fascinated by the arctic and antarctic explorations as well, I might have gone into glaciation had the planetary exploration job not fallen in my lap! I’ve a whole row of the books but have not read this Blizzard one; what a present of a first edition – he really knew your heart! These videos are wonderful. Thank you for the introduction to Mawson.

I am amazed at you too Audrey : broken ribs at the start of your trip and yet you carried on just like these earlier explorers.

And I am waiting very patiently, yes enjoying the lead up, to the Darwin trips pictures. Have you seen Rob Wesson’s Book “Darwin’s First Theory”? Good geology.

What a dream! who knows, maybe somehow somewhere you were connected to that time and the group!