ePostcard #98: There Be Giants: Magellan’s Voyage (Part IV)

ePostcard #98: There Be Giants: Magellan’s Voyage (Part IV)

We rejoin Magellan’s Armada de Molucca in late February as it continues south along the coast of Argentina in search of the elusive strait—if it even exists. Magellan has now adopted measures to ensure that he does not mistakenly sail past any bay or opening along the shore that might be the strait. He anchors at night as close to shore as he dares, and remains focused. After more than six months at sea, Magellan is increasingly confident in his navigational skills in uncharted waters, his ability to anticipate the risks posed by rocky reefs and shallows, and in responding to dangers to the ships and crew posed by the malevolent and frequent storms that plague the fleet. As the fleet ventures closer to 40 degrees latitude (the “Roaring Forties), the weather turns steadily colder as they head into waters notorious for sudden, frequent and violent squalls. Right on schedule they are slammed by yet another powerful storm, which toss the ships as if they were toys, damaging Victoria’s keel, and terrifying the sailors with thunder and lightning and torrential downpours. At the storm’s end, Saint Elmo’s fire appeared on the Trinidad’s masts, lighting the way to a sheltering anchorage and reassuring the sailors that they enjoyed divine protection.

The further south the fleet sailed, the more anxious Magellan became that he had missed the strait altogether. As they sailed into the expansive mouth of Golfo San Matías, Magellan hoped for a miracle because the water was deep and blue and cold, but there was no waterway to be seen. The men might have spotted southern right whales from their ships and if they had sailed closer to shore they would have spotted penguins (yes, Magellanic penguins!), southern sea lions, and southern elephant seals lolling on the beaches. Had they gone ashore, which they did not, they would have seen foxes, the hare-like rodent known as a mara, puma, peregrine falcons, burrowing owls, flamingos, parrots, and hairy armadillos.

In late February, they explored a promising inlet with two islands covered with what seemed to the men like strange ducks or a a kind of goose. They had discovered their first penguins of the voyage! Pigafetta described the birds as too many to count and wonderfully easy to catch. “We loaded all the ships with them in an hour,” he claimed, and they were soon skinned, salted and consumed by the hungry seamen. Six sailors mounted a hunting expedition for “sea wolves,” and landing their longboat on a small island, crept up on several family groups of sea lions. They stunned them with clubs and dragged as many as they could into the longboat. Strong offshore winds blew the ships out to sea, stranding the men on the island. Fearing the worst, Magellan dispatched a a rescue team. The rescuers found the men, alive but exhausted, having spent the frigid night huddled against the bodies of the dead sea wolves.

Each day was a struggle for the Armada de Molucca–Golfo San José, Golfo Nuevo, Bahía de los Patos, Bahía de los Trabajos—every exploration dead-ending in desolate desert country. As the days grew shorter, with the austral winter looming on the horizon, Magellan made the unilateral decision to suspend the search for the strait until the following spring. He turned his attention to finding a safe harbor where the fleet could ride out the winter storms. In late March, Magellan led his fleet into a narrow channel about a half mile wide and flanked by 100-foot high gray cliffs. They named it Puerto San Julién and they would soon learn that the narrow inlet would experience tides of over 20 feet and currents of up to 6 knots. They would have to anchor carefully and run cables to shore to hold their position.

After the unbroken succession of life-threatening ordeals they had faced over the previous seven weeks, the Castilian officers and several of the Portuguese pilots raised their voices in protest, and some suggested that they sail back to Spain. They argued that they did not believe the strait existed, and that if they kept going they would perish in a storm at sea or simply fall off the edge of the earth when the coastline finally ended. Human life must have some value, they insisted, if not to Magellan then surely to King Charles. Magellan had already tested the winds of mutinous rebellion once, and he was certain that the next hell-bent attempt was at hand and would be better planned and launched with deadly stealth. He was right! Pigafetta, normally a thorough chronicler of the voyage, records few details of the brutality and bloodshed that allowed Magellan to triumph over the mutineers in the life and death struggle that began, ironically, on Easter Sunday and continued for several days. There had been executions and torture, but Magellan was once again in full control of the expedition.

Magellan had two goals for the long winter months in Puerto San Julién, to plant a cross on the highest mountain they could climb and to befriend the local indigenous people if they could make contact. The weather soon turned bitterly cold and the intense hardships faced by the men gave rise to increasing discontent. With the prospect of yet another mutiny looming, Magellan, along with all of the crew members, welcomed the distraction provided by an unexpected sight: a distant plume of smoke rising above the hills. Perhaps they were not alone, after all.

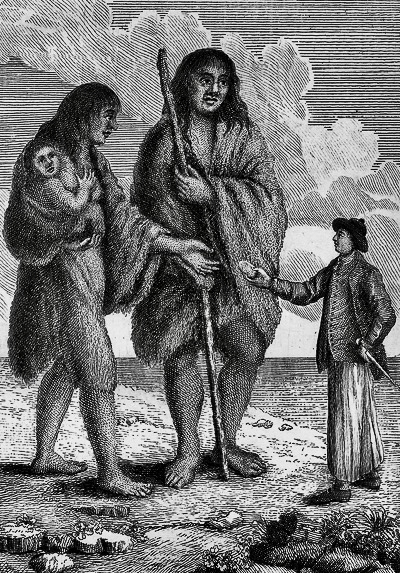

The myth of the Patagonian Giants, like other stories about remote and exotic places, captured the European imagination. The first description of this mythical race is made by Antonio Pigafetta. “We remained two whole months in Puerto San Julién without ever seeing anyone, wrote Pigafetta. ” But one day (without anyone expecting it) we saw a giant who was on the shore, quite naked, and who danced, leaped, and sang, and while he sang he threw sand and dust on his head. Our captain sent one of his men toward him, charging him to leap and sing like the other in order to reassure him and to show him friendship. Which he did. Immediately the man of the ship, dancing, led this giant to a small island where the captain awaited him. And when he was before us, he began to marvel and to be afraid, and he raised one finger upward, believing that we came from heaven. And he was so tall that the tallest of us only came up to his waist. Withal he was well proportioned. . . The captain named the people of this sort Pathagoni.” The etymology of the word is unclear, but Patagonia came to mean “Land of the Bigfeet.” The Patagones are now thought to have been members of the indigenous Tehuelche tribe, a Mapudungun word meaning ‘Fierce People’. They are known to have been taller than the average European (who measured in at roughly five feet), and in all likelihood were the real Goliaths of Patagonia myth and legend. Sadly, as was typical of the age, Magellan seized two of the younger males as hostages to bring back to Spain, but they got sick and died on the journey.

One hundred years later, in The World Encompassed (London, 1628), the first detailed account of Sir Francis Drake’s circumnavigation, the author, Drake’s nephew of the same name, wrote: “Magellan was not altogether deceived, in naming them Giants; for they generally differ from the common sort of men, both in stature, bignes, and strength of body, as also in the hideousnesse of their voice: but yet they are nothing so monstrous, or giantlike as they were reported; there being some English men, as tall, as the highest of any that we could see, but peradventure, the Spaniards did not thinke, that ever any English man would come thither, to reprove them; and thereupon might presume the more boldly to lie: the name Pentagones, Five cubits viz. 7. Foote and halfe, describing the full height (if not some what more) of the highest of them. But this is certaine, that the Spanish cruelties there used [referring to Magellan’s hostage taking], have made them more monstrous, in minde and manners, then they are in body; and more inhospitable, to deale with any strangers, that shall come thereafter.” Drake reduced the height of the Patagonians from ten feet to seven and a half feet but was obviously more intent on discrediting the Spanish and blaming them for the “monstrosity” of the giants. Ironically, though, he was really confirming the basic facts behind the myth.

Maps, Archival Photographs and Captions:

#1. English sailor offering bread to a Patagonian woman giant. Frontispiece to Viaggio intorno al mondo fatto dalla nave Inglese il Delfino comandata dal caposqadra Byron (Florence, 1768), the first Italian edition of John Byron’s A Voyage Round the World in His Majesty’s Ship the Dolphin . . . (London, 1767) [Rare Books Division].

#2. We visited this wonderful replica of the Victoria (built to scale) at the museum in San Julién and you could go inside the ship and get a sense of how small but well-designed it was. After seeing the ship, I was even more impressed by Magellan’s voyage and all that it achieved.

#3. Satellite image of Patagonia, Argentina. Source: European Space Agency (in English: European Space Agency, in French: Agence spatiale européenne, abbreviated ESA by its English abbreviations and ASE by its French abbreviations) The Plateau of Patagonia in Argentina and southern Chile are shown in this Medium Resolution Imaging Spectrometer (MERIS) image. The highest peaks of the Andes (covered by white snow in the image) form a natural boundary between Argentina and Chile and are responsible for the high contrast of the landscape between these two countries. Chile, along the left side of the Andes Mountains, appears mostly green and lush (as can be seen in the top left corner in the image) due to its cool, damp southern climate while Argentina looks dry and brown due to its arid (southeast) and subantarctic (southwest) climes. The southern part of Argentina, known as Patagonia, is the largest desert in the Americas, consisting basically of arid and desolate steppes. Along the Atlantic coast, from top to bottom in the image, can be seen the “Bahía Blanca”, the Gulf of San Matias, the Valdés Peninsula, the Gulf of San Jorge, Cape Tres Puntas (in the centre), and the Grande Bay where a pattern of some periodical waves can be seen in the image due to the existence of strong winds in the area. The tan-green colour in the Bahía Blanca is due to sediments deposited in the water by the Colorado and Negro rivers. On the other hand, bright turquoise lakes seen in the image are the result of extremely fine sediment, highly reflective, deposited by the glaciers.

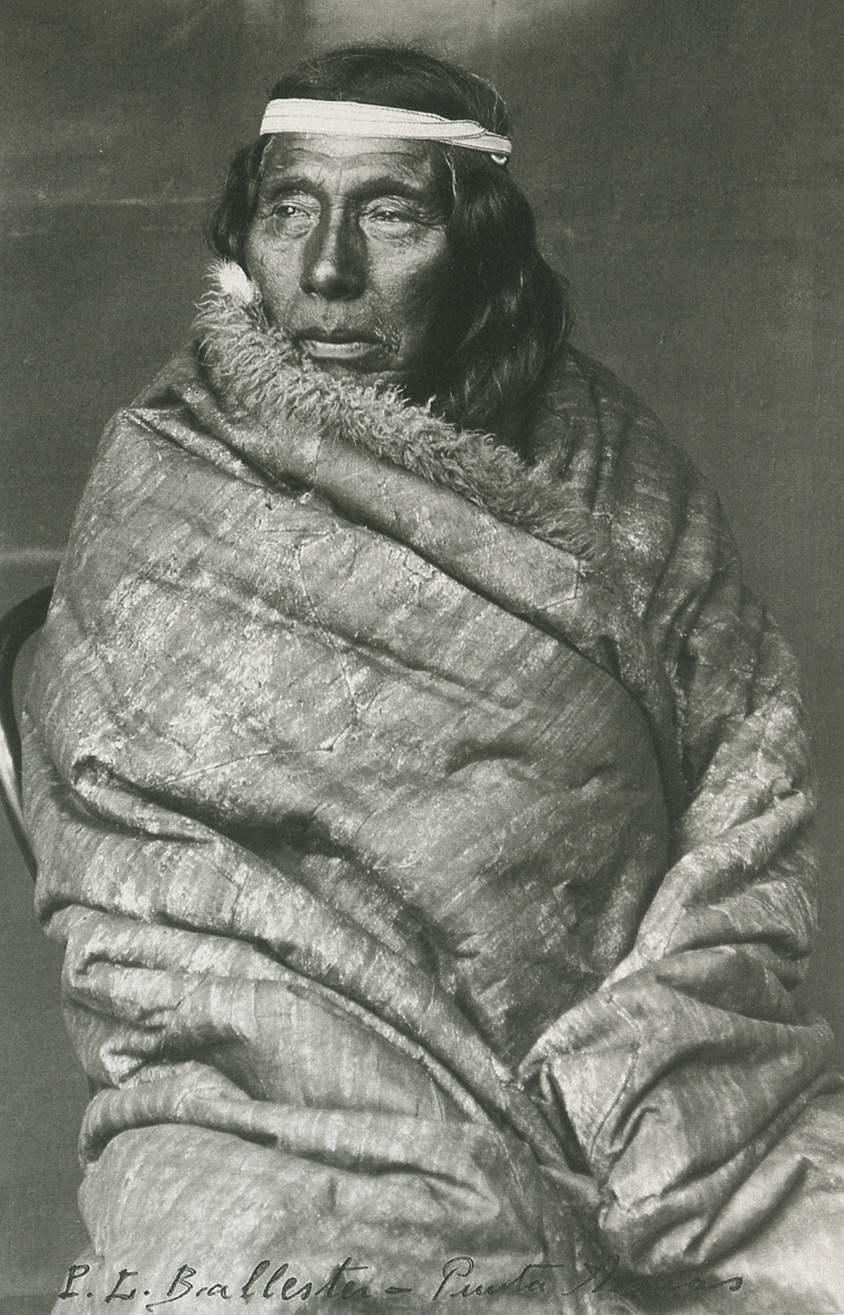

#4. Archival photograph of Cacique Mulato (Punta Arenas,1895), who is considered the last great chief of the Tehuelche. Source: Alisei Collection.

#5. Santa Cruz, 1920; Child Rufino Ibanez, last leader of the Tehuelche with a guanaco cub. Alisei Collection.

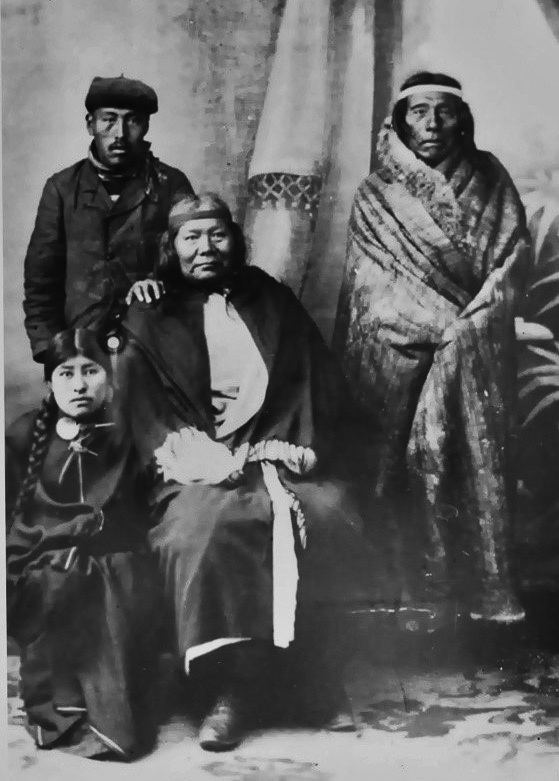

#6. Punta Arenas, 1895; Family group of Cacique Mulato. Alisei Collection.

#7. Santa Cruz, 1900; Family group Tehuelche

#8. Map of Patagonia (modern).

click images to enlarge

click images to enlarge

To help build global awareness, we would appreciate it if you would share this post with your friends and colleagues. Please choose one of the options below which includes email and print! Thank you.