ePostcard #69: Drifting On Ice!

click images to enlarge

ePostcard #69: Drifting On Ice!

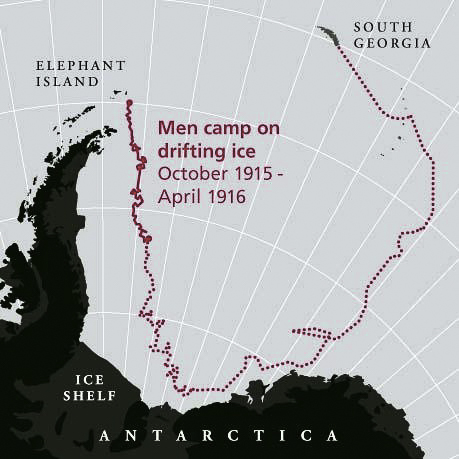

By October, ceaseless pressure from pack ice would force the crew to abandon the Endurance. I can’t imagine what a profoundly emotional departure that must have been. With the ruin of their ship looming behind them, the men set up “Ocean Camp,” a makeshift camp on the ice. Each man was issued warm clothing and a sleeping bag: Shackleton quietly ensured that the warmer reindeer skin bags went to the sailors, while the officers took the less desirable woolen ones. Their most valuable clothing, their Burberry tunics, were the weight of umbrella fabric and windproof but not waterproof. Their five tents were made of linen so thin the moon could be seen through them. With no communication system, no one in the outside world knew where they were. The men resigned themselves to camping on the ice for an indefinite time. A galley and storehouse built from the Endurance’s broken timbers stood in the center of the five tents, while the dogs were pegged nearby in teams. Along with the three life boats, three tons of food supplies were salvaged from the half-sunk ship, and when these ran out the men existed on penguins and seals. From October 1915 to April 1916 the entire expedition team remained camped on the drifting ice pack.

“It is beyond conception, even to us, that we are dwelling on a colossal ice raft, with but five feet of water separating us from 2,000 fathoms of ocean, & drifting along under the caprices of wind & tides, to heaven knows where.” Frank Hurley, Diary

‘She’s going, boys!’ Shackleton shouted the evening of November 21, 1915. The men were out in a second and up on the look-out station and other points of vantage, “and, sure enough, there was our poor ship a mile and a half away struggling in her death-agony. She went down bows first, her stern raised in the air. She then gave one quick dive and the ice closed over her forever. It gave one a sickening sensation to see it, for, mastless and useless as she was, she seemed to be a link with the outer world. Without her our destitution seems more emphasized, our desolation more complete.”

As always, Shackleton was as concerned with his men’s morale as with their physical well-being. He knew that as their leader his every word and gesture would be critical in these vulnerable days. Dr. Alexander Macklin reports that in the aftermath of the disaster, Shackleton assembled his men and calmly told them: “Ship and stores have gone, so now we’ll go home.” The men’s sleeping bags were alternately sodden from melted snow and frozen as stiff as sheet metal. Day by day, the dwindling floe of ice on which they were camped drifted north toward open sea. With the high temperatures, surface-thaw set in, their bags and clothes were soaked and sodden. They lived in “a state of perpetual wet feet.” At night, before the temperature had fallen, clouds of steam could be seen rising from their soaking bags and boots. As it grew colder, this all condensed as rime on the inside of the tents, and showered down upon the occupants if someone happened to touch the side inadvertently.

The first half of December they kept a close eye on the wind and believed it would help to open the ice and form leads through which they might escape to open water. On December 20, Shackleton informed all hands that he intended to try and make a march to the west to reduce the distance between them and Paulet Island. A buzz of anticipation went round the camp, he wrote, and everyone was eager to get on the move. The next day he set off with Wild, Crean and Hurley, with dog teams, to survey the route. At first, Shackleton hoped to march to land some 300 miles to the northwest, hauling the lifeboats and sledging rations that had been evacuated from the Endurance. Knowing they would have to travel light, Shackleton announced that only bare necessities could be taken; dramatically he deposited his own gold watch and the ship’s Bible on the ice by way of example. Puppies born on board the ship and Mrs. Chippy, the cat, were shot, much to the regret of all.

From Shackleton’s diary: “December 22 was honored as Christmas Day, and most of our small remaining stock of luxuries was consumed at the Christmas feast. We could not carry it all with us, so for the last time for eight months we had a really good meal—as much as we could eat. Anchovies in oil, baked beans, and jugged hare made a glorious mixture.” On December 23rd all hands were roused in the wee hours for the purpose of sledging the two boats, the James Caird and the Dudley Docker, over the dangerously cracked portion to the first of the young floes, while the surface maintained it’s icy night crust. Shackleton’s intention was to sleep by day and march by night, so as to take advantage of the slightly lower temperatures and consequent harder surfaces. Each day, Wild and Shackleton would go ahead for two miles or so to reconnoitre the next day’s route, marking it with pieces of wood, tins, and small flags. Pressure-ridges had to be skirted, and where this was not possible the best place to make a bridge of ice-blocks across the lead or over the ridge had to be found and marked.

Every day Shackleton pioneered in front, followed by the cook and his mate pulling a small sledge with the stove and all the cooking gear. Next came the dog teams, who quickly overtook the cook, and the two “cumbrous” boats brought up the rear. Progress was slow and they relayed gear, but dared not abandon the boats on any account, according to Shackleton. On the 25th, a breakfast of sledging ration was served. By a couple hours past midnight they were on the march. “We wished one another a merry Christmas, and our thoughts went back to those at home. We wondered, too, that day, as we sat down to our “lunch” of stale, thin bannock and a mug of thin cocoa, what they were having at home.” On the 27th, at 9 p.m. they started marching. “The first 200 yds. took us about five hours to cross, owing to the amount of breaking down of pressure-ridges and filling in of leads that was required. The surface, too, was now very soft, so our progress was slow and tiring. We managed to get another three-quarters of a mile before lunch, and a further mile due west over a very hummocky floe before we camped at 5.30 a.m.”

Shackleton diary entries: “December 29.—After a further reconnaissance the ice ahead proved quite un-negotiable, so at 8.30 p.m. last night, to the intense disappointment of all, instead of forging ahead, we had to retire half a mile so as to get on a stronger floe, and by 10 p.m. we had camped and all hands turned in again. The extra sleep was much needed, however disheartening the check may be.”

Shackleton eventually made two attempts to march to land, both futile. The dogs successfully hauled the sledges loaded with supplies, but it was left to the men to pull the lifeboats. Loaded, the boats weighed at least a ton each, and it proved impossible to haul them over the colossal upheavals of ice. Nor could the boats be left behind, as beneath the unreliable ice was the ocean, countless fathoms deep. Helplessly, the men watched to see if the drift of the pack would carry them to land. Meanwhile, they could only wait. The men named their second encampment “Patience Camp.”

Shackleton diary entries: “During the night a crack formed right across the floe, so we hurriedly shifted to a strong old floe about a mile and a half to the east of our present position. The ice all around was now too broken and soft to sledge over, and yet there was not sufficient open water to allow us to launch the boats with any degree of safety. We had been on the march for seven days; rations were short and the men were weak. They were worn out with the hard pulling over soft surfaces, and our stock of sledging food was very small. We had marched seven and a half miles in a direct line and at this rate it would take us over three hundred days to reach the land away to the west. As we only had food for forty-two days there was no alternative, therefore, but to camp once more on the floe and to possess our souls with what patience we could till conditions should appear more favorable for a renewal of the attempt to escape. To this end, we stacked our surplus provisions, the reserve sledging rations being kept lashed on the sledges, and brought what gear we could from our but lately deserted Ocean Camp. Our new home, which we were to occupy for nearly three and a half months, we called Patience Camp.”

click images to enlarge

To help build global awareness, we would appreciate it if you would share this post with your friends and colleagues. Please choose one of the options below which includes email and print! Thank you.