ePostcard #70: Elephant Island!

click images to enlarge

ePostcard #70: Elephant Island!

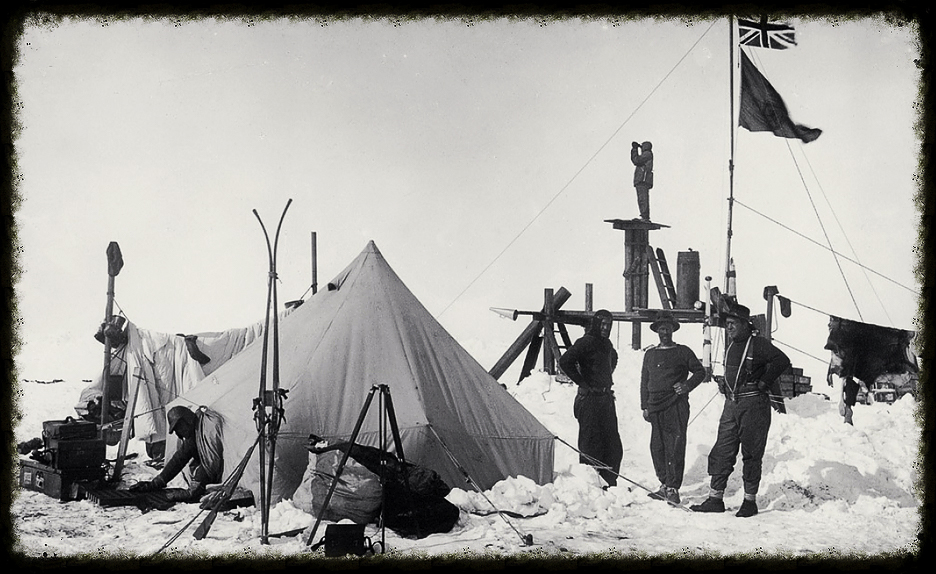

After months spent in makeshift camps on the northward drifting pack ice, the situation for Shackleton and his men had become increasingly dire. At Patience Camp in early March (photo #1; left to right: Wild, Worsley, Shackleton), the expedition’s engineer Orde-Lees reported feeling seasick. Faced with the grim reality that the ice had become so thin that the swell of the ocean could be felt beneath their feet, Shackleton knew that their survival depended on having the lifeboats mostly loaded and ready to launch at a moment’s notice. At the end of March, the last of their beloved dogs were shot, and eaten. The March temperatures ranged from highs in the 30’s to a low of -21 degrees Fahrenheit, with a mean temperature of 1 degree. On April 9, 1916, the 28 men struck camp and piled into the three life boats. At the mercy of prevailing winds, they set their course for Elephant Island, located some 100 miles to the north. This terrible journey, made in heaving seas, nearly cost many of the men their lives, and some a measure of their sanity. On the 15th of April, the seventh day out from Patience Camp, the lifeboats arrived at Elephant Island.

Landing through the storm-driven surf at Elephant Island was extremely treacherous and the men were already soaked, frozen and racked with thirst after an exhausting six-day boat journey. Photograph #2 shows the third lifeboat landing and the men rushing to help pull the last boat safely ashore. Photograph #3 shows all three lifeboats being secured. Photograph #4 shows the meager supplies being staged in piles on the beach. This was their first time on dry land in nearly 500 days. Shackleton recorded the near-hysterical reactions of the men in his diary: “They were laughing uproariously, picking up stones and letting handfuls of pebbles trickle through their fingers like misers gloating over hoarded gold.” Photograph # 5 shows eight men standing around a stove, drinking from mugs and tankards. From left to right are: J Ord Lees [engineer]; J Wordie [geologist]; R Clark [biologist]; L Richardson [chief engineer]; L Greenstreet [chief officer]; Howe; Ernest Shackleton; Bakewell; A Kerr [2nd engineer] and Frank Wild.

During the first two weeks ashore, knowing that no whaling ships would ever spot them on this remote island, Shackleton made the decision to select five of the expedition’s toughest and best sailors—Worsley. Crean, McNeish, McCarthy, and Vincent—to mount a desperate rescue mission to reach the whaling stations of South Georgia, over 800 miles away and across the most dangerous stretch of ocean on the planet. Shackleton and the five men would sail the largest and most seaworthy of their lifeboats, the James Caird, navigating by sextant under stormy skies that might well prevent a single celestial sighting. As blizzards raged through their beach camp, McNeish, the carpenter, labored to equip the 22-1/2-foot James Caird for the ordeal ahead, raising her sides and covering her topside with a “roof” made from tent fabric to provide shelter for the men photo#6) during the voyage. It would be an incredible feat of navigation and seamanship if the six men even survived the voyage to South Georgia. Shackleton would leave his trusted second-in-command, Frank Wild, in charge of the 22 men who remained on Elephant Island (photo #7). The storm-battered island would be “home” for nearly five months while the men stoically waited for “the Boss” to return from his heroic voyage with a rescue ship to save them all. The mood in camp must have been fraught with emotional turmoil and fear. As they watched the James Caird sail away, Wild’s comment below says it all.

“We gave them three hearty cheers & watched the boat getting smaller & smaller in the distance. Then seeing some of the party in tears I immediately set them all to work.” (Frank Wild, Memoir)

On Elephant Island the men’s circumstances were bleak. Some of the men were frostbitten or in poor health, while others were mentally unstable due to the unrelenting stress. The island was “almost continuously covered with a pall of fog and snow,” according to meteorologist Leonard Hussey. For two weeks following the rescue team’s departure, gale force winds blew without cessation, at times reaching wind speeds of over one hundred miles an hour. Their clothing was now threadbare and afforded little protection. With the incessant storms, they also discovered that their “safe haven” on the beach lay below the high-water mark. Under Wild’s persistent command, the men labored to improve their living conditions by small degrees. Knowing that they would need more durable shelter than their ruined tents could provide, the men tried digging ice caves at the front of a nearby glacier. Frustrated by icy meltwater, they finally made the decision to build a survival hut with the two remaining lifeboats (Dudley Docker and Stancomb Wills), which they turned upside down and then insulated with the remains of the tattered tents. The hut was about 5’ high, and the men slept on the pebble floor or in hammocks suspended from the roof (photo #7) Later refinements included a chimney and two small windows. Makeshift blubber lamps gave off dim light. Wild organized daily hunting expeditions along the narrow beach. In the evening “sing-songs” relieved the tedium of their second polar night, the three months of darkness that occurs annually in the Antarctic. Crammed into their small shelter, the men survived on a diet of penguin and seal, and their chief topic of conversation was food. The hut became black with blubber smoke, and the shingle floor became a mess of mud, blubber and other waste. Hurley took these final photographs with a pocket camera, the only one he had saved from the Endurance, and three rolls of film. The images are amazing but more grainy than his other work, which is in keeping with the difficult conditions they had to endure.

click images to enlarge

To help build global awareness, we would appreciate it if you would share this post with your friends and colleagues. Please choose one of the options below which includes email and print! Thank you.

Having read the Endurance and being so excited that our trip was designed on the footsteps of Shackleton, it was, it was disappointing to me that because of bad weather , we did not stop.

Such an epic chapter.. Thanks Audrey