ePostcard #71: South Georgia Bound!

click images to enlarge

ePostcard #71: South Georgia Bound!

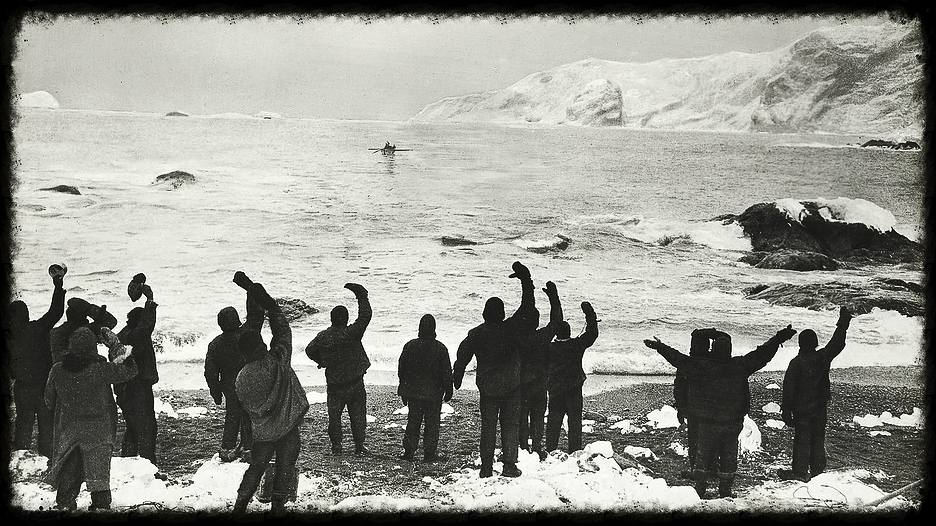

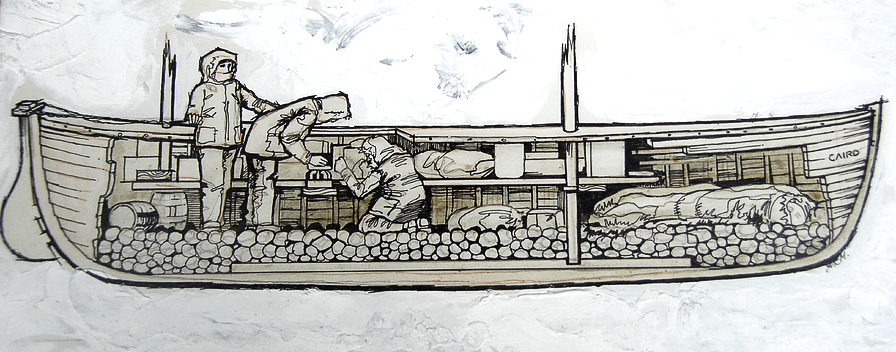

The perilous voyage of the James Caird from Elephant Island to South Georgia is ranked as one of the greatest boat journeys ever accomplished and is an achievement unique in the history of exploration. Shackleton faced the horrifying realization that the only way he could save the lives of his men on Elephant Island would be to sail one of the three lifeboats to South Georgia and seek rescue help from the whalers. The James Caird was deemed the strongest and most likely to survive the journey. The boat had been named by Shackleton after Sir James Key Caird, a Dundee jute manufacturer and philanthropist, whose sponsorship had helped finance the expedition. To prepare for the voyage the boat was strengthened and adapted by the ship’s carpenter Harry McNish to withstand the ferocious pounding the small boat would receive in the Southern Ocean. The drawing (photo #3) provides a cut-away view of the James Caird. Note the beach rock ballast along the length of the hull and the storage and sleeping space atop the ballast. Some 250 pounds of ice was gathered to supply fresh drinking water for the six men. Frank Worsley’s navigation “instrumentation” consisted of a sextant, the ship’s chronometer, aneroid (barometer), prismatic compass, some charts, and a pair of binoculars. Photograph #4 is an unknown painter’s portrayal of the James Caird underway and approaching South Georgia. Having been aboard an expedition ship in the Drake Passage in 35-foot seas, I can attest that the painter’s depiction captures the tumultuous peril of their voyage.

Read this excerpt from Shackleton’s own accounting of one of the most horrific experiences during the voyage, and imagine yourself at sea aboard the James Caird.

On their 11th day at sea (May 5), a tremendous cross-sea wind developed and at midnight, while Shackleton was at the tiller, a line of clear sky was spotted between the south and south-west. Shackleton wrote, “I called to the other men that the sky was clearing, and then a moment later I realized that what I had seen was not a rift in the clouds but the white crest of an enormous wave. During twenty-six years’ experience of the ocean in all its moods I had not encountered a wave so gigantic. It was a mighty upheaval of the ocean, a thing quite apart from the big white-capped seas that had been our tireless enemies for many days. I shouted ‘For God’s sake, hold on! it’s got us.’ Then came a moment of suspense that seemed drawn out into hours. White surged the foam of the breaking sea around us. We felt our boat lifted and flung forward like a cork in breaking surf. We were in a seething chaos of tortured water; but somehow the boat lived through it, half full of water, sagging to the dead weight and shuddering under the blow. We bailed with the energy of men fighting for life, flinging the water over the sides with every receptacle that came to our hands, and after ten minutes of uncertainty we felt the boat renew her life beneath us.”

The next day, May 6, Worsley determined that they were not more than a hundred miles from the northwest corner of South Georgia. On May 8, just fourteen days after departing Elephant Island, McCarthy caught a glimpse of the black cliffs of South Georgia. When the storm clouds lifted just enough to reveal the mountainous backbone of the island, Shackleton realized that the winds had forced them to the opposite side of the island from the whaling stations. After being blown back out to sea in one of the worst storms Shackleton had ever experienced, they were able to turn back towards South Georgia on May 10. Sighting an indentation along the coast gave then hope that they might be able to slip between a gauntlet of angry reefs and a wall of glacial ice and find shelter in a small bay. Unable to determine precisely where they were along South Georgia’s coast and desperately thirsty, Shackleton guessed correctly that they were near the mouth of King Haakon Bay and made the decision to attempt a landing. As they approached in the gathering darkness, the men pulled in the oars and were silent as the James Caird glided into the narrow entrance on the swell and touched down on the beach. In Shackleton’s words: “Then we attempted to pull the empty boat up the beach, and discovered by this effort how weak we had become. Our united strength was not sufficient to get the James Caird clear of the water.” At 2 a.m. on that first night ashore, Shackleton woke everyone, shouting, “Look out boys, look out! Hold on! it’s going to break on us!” It was a nightmare…. Shackleton thought the black snow-crested cliff above them was a giant wave.

The astounding fact that the James Caird and the six men survived the 800-mile voyage to South Georgia remains a lasting tribute to Shackleton’s leadership and the incredible navigational skills of New Zealander Frank Worsley. Worsley had only been able to take sightings of the sun four times, on April 26th and May 3rd, 4th and 7th, all the rest had been dead reckoning, keeping on the same straight line in the same heading. After a couple days of rest, the men repositioned the James Caird and made a more substantial camp on the north side of King Haakon Bay. With McNish and Vincent still too weak to attempt the trek to the Stromness Whaling Station, Shackleton put McCarthy in charge of the men’s care and support until they could return with a rescue ship.

Shackleton, Crean, and Worsley had one final daunting challenge to survive—a 22-mile alpine traverse over South Georgia’s mountainous spine and crevasse-riven glaciers to get help from the Norwegians at Stromness—so close, yet so far. Shackleton’s remaining pair of boots were in such poor condition that McNish removed a few screws from the James Caird and hammered them through the boot’s soles to give “the Boss” better traction on the glacier ice. Since the men had no intention of stopping until they reached Stromness, their provisions were minimal, and included two compasses, the ship’s chronometer, a walking stick for each man made from the boat’s decking, a single 90-foot coil of rope, a Primus oil stove for making tea, rations for 6 meals, and McNish’s adze to be used as an ice axe. On May 15, the men set out on their journey with determination and resolve—they would make it to Stromness or perish in the effort. In the event that something happened to them, Shackleton left a final directive in McNish’s diary that commanded the three men to remain in their camp until relief arrived. Shackleton then wrote his final assurance: “I trust to have you relieved in a few days. Yours faithfully, E. H. Shackleton”

click images to enlarge

To help build global awareness, we would appreciate it if you would share this post with your friends and colleagues. Please choose one of the options below which includes email and print! Thank you.