ePostcard #74: The Final Rescue!

click images to enlarge

ePostcard #74: The Final Rescue!

“Not a life lost, and we have been through Hell!”

Ernest Shackleton

This opening photo by Frank Hurley takes us back to where it all began—South Georgia. You can see the Endurance, dwarfed by her mountainous surroundings, anchored in the bay at Grytviken. The two men admiring the panoramic view from atop Mt. Duse are Captain Frank Worsley and First Officer Lionel Greenstreet. It is hard not to wonder what the men were thinking on that glorious day more than a 100 years ago.

The arrival of Shackleton, Worsley and Crean at Stromness, after an historic crossing of the island in just 36 hours, is remarkable but certainly not the end of this extraordinary saga. Wrote Shackleton, “Our first night at the whaling station was blissful. We were so comfortable that we were unable to sleep. With all 6 of the James Caird rescue party finally reunited at Stromness, Shackleton faced yet another race against time to rescue the 22 men, the majority of the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition team, who were still marooned on the desolate snow and ice covered barrens of Elephant Island. Had the shelter the men built of their two overturned lifeboats (nicknamed ‘the Snuggery’) provided enough protection for the men from the harsh elements? With the help and resources at the whaling stations, Shackleton immediately organized a rescue mission for the men on Elephant Island, but the elements worked against them. Three separate attempts – aboard the Southern Sky in May, the Instituto Pesca No. 1 in June, and the Emma in July – are all forced to turn back as pack ice threatens to entrap them just as it had the ill-fated Endurance. ‘I entertained very grave fears,’ writes Shackleton. ‘Six hundred miles away my comrades were in dire need.’ Shackleton was to write in a letter to a friend, “When we got to the whaling station, it was the thought of all those comrades that made us so mad with joy… We didn’t so much feel safe as that they would be saved”

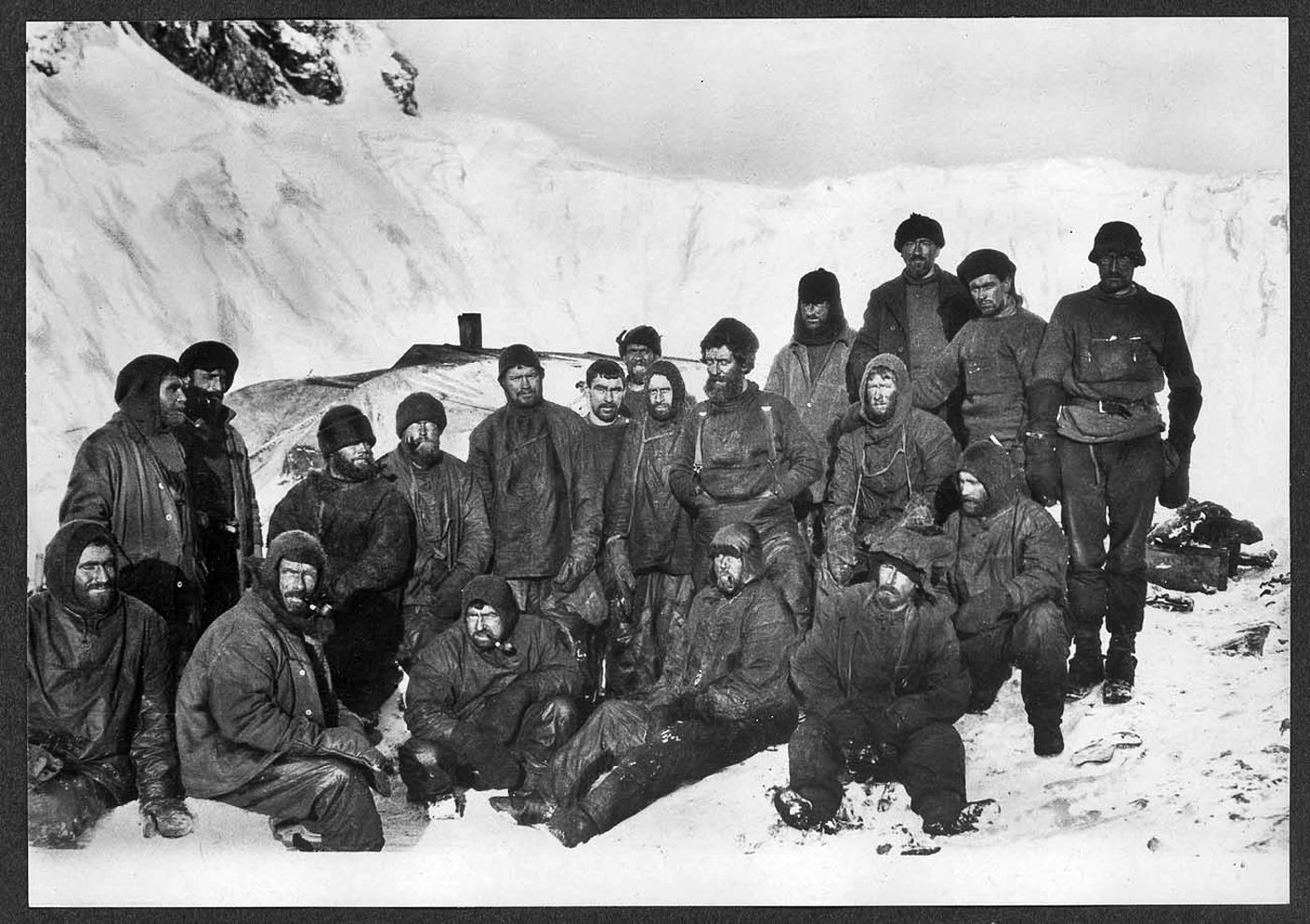

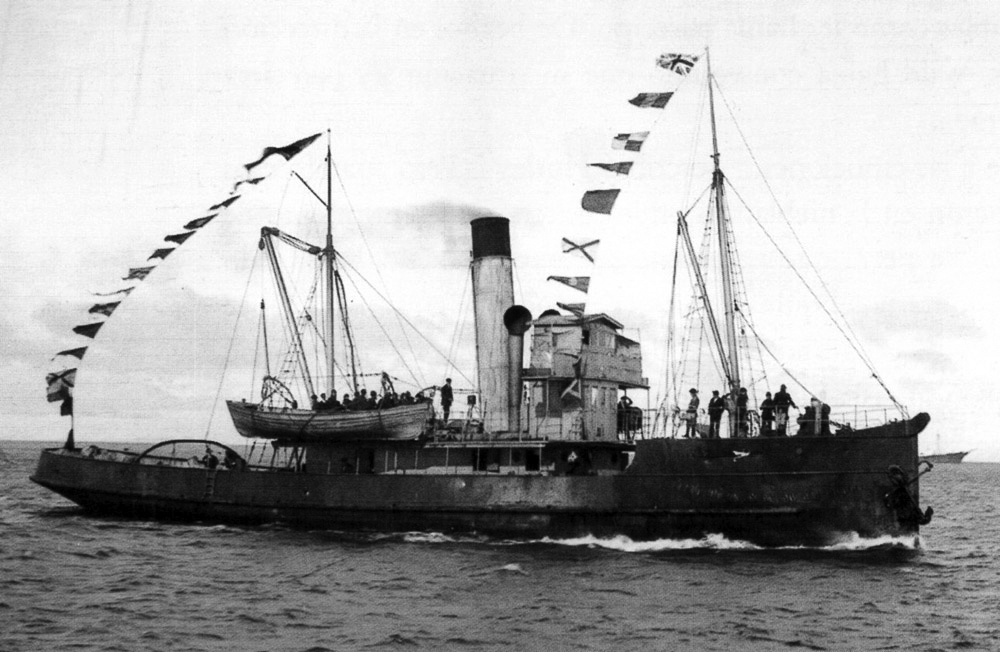

On Elephant Island, the men have had enough penguins and seals keep them alive, providing meat to eat and blubber for cooking and ice to melt for drinking water. But winter has set in, freezing cold, dark and oppressive. ‘The weather is wretched,’ writes photographer Frank Hurley. (Photo#2) ‘A stagnant calm of air and ocean alike, the latter obscured by heavy pack ice, and a dense wet mist hangs like a pall over land and sea.’ Conditions on the island are rapidly deteriorating. Pearce Blackborow, the stowaway who had gone on to become the ship’s steward, suffers severe frostbite in his left foot. The medical situation has become so dire that the expedition’s doctors, Macklin and McIlroy, are forced to amputate his toes. ‘In spite of the extremely unfavorable conditions,’ notes Hurley, ‘the operation was eminently successful.’ Finally, on August 30, 1916, over four months after first landing on the island, hope arrives for the men with Shackleton’s fourth attempt—the Chilean steam tug Yelcho with Piloto Luis Alberto Pardo at the helm.

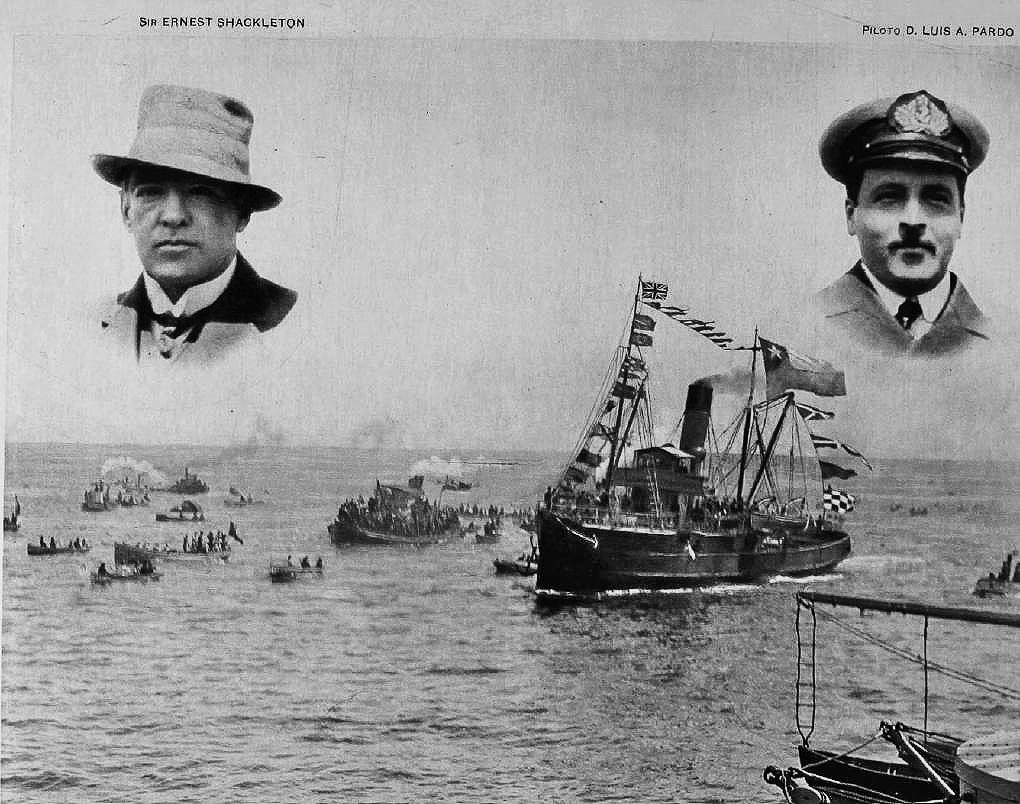

By then, the men had been stranded on the island for 128 days. Hurley took photograph #4 in this series from the beach camp (note the beacon fire to the left in the photo) of the rescue ship approaching the men. ‘Day of Wonders,’ writes Hurley. The men were gathered around a lunch of soiled seal carcass, some shelling limpets, when Marston (the expedition’s artist) Marston spots the Yelcho in an opening in the mist. He yelled, “Ship O!” but the men thought he was announcing lunch. A few moments later the men inside the hut heard him running forward, shouting, “Wild, there’s a ship! Hadn’t we better light a flare?” As they scrambled out the door, those bringing up the rear tore down the canvas walls. Wild put a hole in their last tin of fuel, soaked clothes in it, walked to the end of the spit and set them afire.The air fills with cheering as the men run to the shoreline to see the Yelcho heading towards them. The boat soon approached close enough for Shackleton, who was standing on the bow, to shout to Wild, “Are you all well?” Wild replied, “All safe, all well!” and the Boss replied, “Thank God!” Blackborow, since he couldn’t walk, was carried to a high rock and propped up in his sleeping bag so he could view the scene.

Frank Wild invited Shackleton ashore to see how they had lived on the Island, but he declined being keen to be on their way as soon as possible in the light of previous failed attempts to reach the men due to ice conditions. “I hurried the party aboard with all possible speed,” Shackleton wrote, “taking also the records of the Expedition and essential portions of equipment. Everybody was aboard the Yelcho within an hour, and we steamed north at the little steamer’s best speed. The ice was still open, and nothing worse than an expanse of stormy ocean separated us from the South American coast.”

They were finally headed north to the world from which no news had been heard since October, 1914; they had survived on Elephant Island for 137 days, it was 128 days since Shackleton had left for South Georgia with his small crew on the James Caird. Two years and 22 days since first leaving Plymouth, and nearly 21 months since they first set sail from South Georgia, the men are finally safe and heading home. Four days later the Yelcho docks in Punta Arenas, Chile, where a crowd turns out to witness the triumphant arrival.

“I have done it,” writes Shackleton, in a message to his wife Emily. “Not a life lost, and we have been through Hell!”

Photo Captions:

#1: Back to where it all began in 1914! South Georgia (part of a panorama) with Frank Worsley and Lionel Greenstreet looking down on the Endurance from Mt. Duse. (Frank Hurley)

#2: Frank Hurley, photo taken by a crew mate, in front of the Snuggery hut on Elephant Island.

#3: Hurley’s final photo of the group after three months waiting for rescue on Elephant Island.

#4: Wild sets off a smudge beacon above the camp to mark their location, the men watch the approach of a ship on the horizon.

#5 & #6: The Chilean vessel Yelcho stands ready to deploy their lifeboat to begin the rescue of the 22 men on Elephant Island.

#7: The postcard created to celebrate the Yelcho arriving back in Punta Arenas, Chile with the rescued crew of the Endurance, with Sir Ernest Shackleton (left) and Luis Alberto Pardo (right), the captain of the Yelcho.

click images to enlarge

FURTHER READING OR VIEWING:

2. The Endurance – Shackleton’s Legendary Expedition (2000)

PBS NOVA, dramatization with original footage

To help build global awareness, we would appreciate it if you would share this post with your friends and colleagues. Please choose one of the options below which includes email and print! Thank you.